When President Duterte assumed office in 2016, maNy had hoped that he – or at least his Cabinet – would finally get rice policy right.

But it now seems such hopes were largely premature and illusory. In fact, Duterte’s rice policies of late are so bad that stocks of cheap NFA (National Food Authority) rice have been depleted – for the first time in decades – while commercial rice prices have spiked.

In this article we confirm this using data, explore possible reasons why this happened, and propose solutions that could turn around Duterte’s bungled rice policies.

Depleted stocks

Let’s begin with hard data showing the alarming depletion of NFA rice stocks under Duterte’s watch.

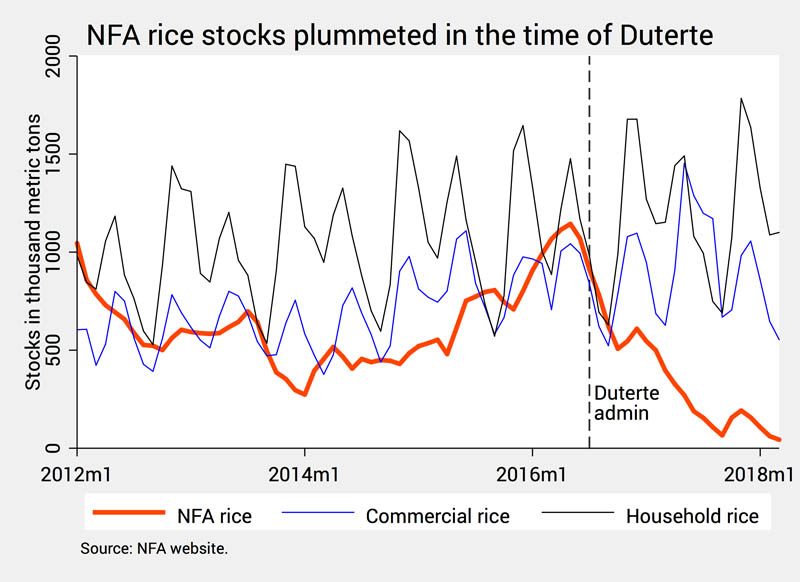

Figure 1 shows that, years before Duterte assumed office, the stocks of all types of rice – NFA rice, commercial rice, and household rice – roughly followed the same trends, or at least never strayed too far from one another.

But since Duterte came, NFA rice stocks (denoted by the orange line) have deviated from the rest and plummeted at an alarming rate. By early April 2018, NFA rice has essentially been “wiped out” in warehouses and markets nationwide.

Figure 1.

The LEDAC (Legislative-Executive Development Advisory Committee) requires the NFA to keep at least 15 days' worth of buffer stock at all times.

But now, we’ve run out of subsidized rice – the first time this has happened since NFA’s creation in 1972, or in nearly 50 years.

Granted, there’s still commercial rice to be bought from markets, and 250,000 metric tons are set to replenish NFA supplies as early as May.

NFA stocks are also very tricky to manage: the NFA’s business model of buying high and selling low is inherently unprofitable, and forecasting the right amount of rice to import is fraught with so much uncertainty that it often leads to over- or under-importation.

But the precipitous drop of NFA rice stocks of late is no less shocking because it was needless and totally avoidable.

Where’s the rice?

Where did all the NFA rice go?

For starters, some observed that, last year, the NFA, for some reason, flooded the market with rice during the harvest season and restricted supply during the lean season. This is the exact opposite of how a buffer stock ought to work.

Moreover, a number of dubious transactions suggest gross mismanagement by NFA Administrator Jason Aquino. Most recently, Aquino allegedly diverted 10.4 million kilos of NFA rice from Region VIII and sold them to select rice traders in Bulacan. (READ: NFA’s Aquino diverted E. Visayas rice to Bulacan traders – memo to Duterte)

This much was divulged in a memo by Cabinet Secretary Jun Evasco Jr. who, until recently, headed the interagency NFA Council in charge of overall rice policy.

All the charges against Aquino have been downplayed by the NFA spokesperson. But some strongly believe that the significant transaction authorized by Aquino had a direct hand in the dwindling of NFA rice stocks at least in Eastern Visayas.

How many more dubious deals have the NFA made under the public’s nose and in other parts of the country?

Infighting in the Cabinet

What’s more, despite all the red flags, Duterte seems to be turning a blind eye to Aquino’s gross mismanagement of the NFA.

Instead of punishing Aquino – or at least suspending him – Duterte even recently removed Cabinet Secretary Evasco from the NFA Council and reverted supervision of the NFA to the Department of Agriculture.

This is not the first time Duterte has favored Aquino over Evasco. Last year Duterte fired on live TV one of Evasco’s most trusted assistants, then Palace undersecretary Halmen Valdez, on wrong accusations that she allowed rice imports that will hurt local farmers (the issue is more nuanced than that).

In a recent meeting with rice traders, Duterte even threatened to abolish the NFA Council altogether (even though he cannot do this unilaterally).

Such a move would be pernicious to the country since the NFA Council was established precisely to inoculate subsidized rice from politics and corruption, and reduce the enormous discretion often enjoyed by those who handle it.

Abolishing the NFA Council would only open the floodgates to more shady deals by the NFA, which we now have reason to suspect given Evasco’s damning evidence against Aquino.

In addition, Aquino’s preferred method of rice importation – government-to-government (G2G) – is more prone to corruption and financial strain vis-à-vis government-to-private sector (G2P) importation.

Aside from being exempt from the Procurement Law, every G2G transaction requires the government to take new loans from Landbank. A one-million-ton rice import, for example, would necessitate incurring P24 billion of extra debt from Landbank.

To address the recent depletion of NFA rice, Duterte green-lighted the importation of rice via G2G. But with the oversight function of the NFA Council now gone, who will make sure this and NFA’s future G2G imports will be transparent, corruption-free, and efficient?

In the end, Jason Aquino’s mismanagement of the NFA has transcended mere “whiff or whisper” of corruption, yet Duterte’s hands still seem inextricably tied. Why? One clue may lie in the fact that Aquino enjoys a direct link to Special Assistant to the President Bong Go.

Scarcer, costlier rice

Whether caused by politics, corruption, or plain old incompetence, rice is now scarcer and costlier, thanks to Duterte’s botched rice policies.

Markets are coping, for example, through a flurry of smuggling activities. On April 14, a Mongolian vessel was spotted off Zamboanga Sibugay unloading to two other vessels 7,000 to 8,000 sacks of rice from Viet Nam (the ship carried a total of 27,180 sacks worth P68 million).

Smuggling is often a manifestation of unmet demand. But government, by itself, cannot quickly address rice shortages as long as the NFA has the sole authority to import it.

Economists have long argued that abolishing NFA’s rice importation monopoly – and leaving rice importation to market forces – could minimize the need for (and profitability of) rice smuggling.

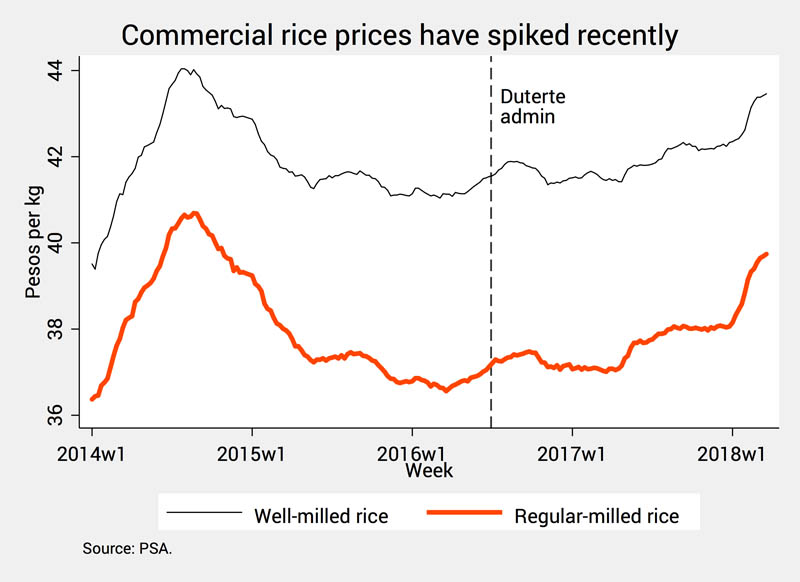

Amid the shortage of NFA rice, the poor are also left with no choice but to buy more commercial rice. But thanks to classic supply and demand, this has led to a recent spike of commercial rice prices (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

This, in turn, has contributed to a higher-than-expected inflation rate (that is, a faster rise of prices) in recent months – on top of other factors like higher world oil prices (at a 3-year high), the weaker peso (at an 11-year low), and the inflationary impact of TRAIN.

With the poor devoting as much as two-thirds or three-quarters of their budgets on rice alone, higher inflation’s impact on their incomes becomes even larger.

In view of rice’s singular importance to inflation, some economists have proposed a number of changes in rice policy that could abate inflation’s impact on the poor.

One is to “tarrify” the import quotas of rice – that is, convert the import quotas into their equivalent tariffs. Not only could this reduce the special privileges enjoyed by certain rice traders, but it could also generate revenues that government could earmark for programs directed specifically at poor farmers.

Another is to reduce rice import quotas significantly and allow rice supplies to be determined freely by the market. Here, the NFA wouldn’t lose all reason for its existence; it could still maintain a small buffer stock for emergencies. (READ: Rice in the time of Duterte: Will more imports be good?)

Although some Cabinet members have voiced out these and other sound policy recommendations, lobbying and infighting among Duterte’s minions continue to prevent these proposals from seeing the light of day.

In other words, even while we’re looking for solutions, politics continues to bedevil rice policy.

Low-hanging fruit

For a nation consuming so much rice, one would think that, by now, our government should be an expert in rice policy.

But decades since the creation of the NFA, rice policy seems as rife with mismanagement and corruption as ever.

This is unfortunate. Many experts agree that rice policy is one of the lowest-hanging fruits of good public policy. Done well, it can swiftly improve the lives of millions of Filipinos, especially the poor.

“Tariffying” rice import quotas or substantially reducing them, for example, could help ensure more and cheaper rice for our people, which we need especially now that inflation has gone through the roof.

But unless the Duterte government sets aside politics, tempers opportunism among its ranks, and gets its act together, plentiful and cheap rice will be as far beyond our grasp as ever. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate and teaching fellow at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter: @jcpunongbayan.