Like many things that happen in this administration, Boracay's closure started with a presidential rant.

Like many things that happen in this administration, Boracay's closure started with a presidential rant.

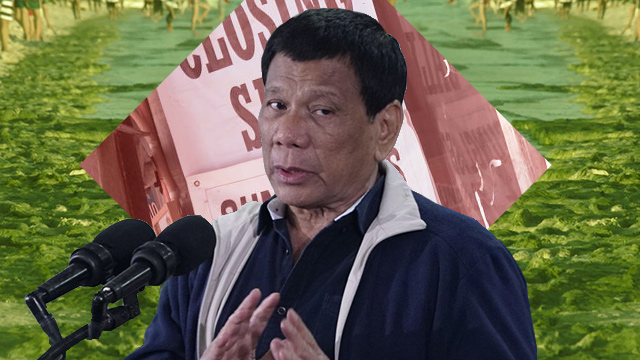

Speaking at a business forum in his home court Davao City last February 9, President Rodrigo Duterte called Boracay a cesspool, saying its waters smelled like shit. He then threatened to close down the island and ordered Environment Secretary Roy Cimatu to “clean the goddamn thing” in 6 months.

Duterte's anger was not misplaced. Boracay's problem is not only its lack of adequate sewage and wastewater treatment facilities. Also glaring is the rampant violation of zoning rules, particularly the required 30-meter setback for structures along the shore and 6-meter setback from the center of the island's roads. Then there's the illegal reclamation of the island's wetlands and occupation of designated forest lands.

All this, plus the unregulated entry of residents, temporary settlers, and tourists have imposed a heavy toll on the island's ecosystem, making it unsustainable and dangerous.

It's a problem that's long been identified but ignored and made worse by corrupt officials from the barangay to the national agencies, all colluding to feast on Boracay's estimated P56-billion annual income.

A solution without a plan

But just like any rant, Duterte's threat to close down Boracay was an off-the-cuff remark. Surprised Cabinet officials found themselves scrambling to interpret, justify, and operationalize something they were not prepared to do. (READ: Enough of policymaking without planning}

As late as April 4, when Duterte announced that Boracay would be closed starting April 26, he admitted that there was no masterplan for the 6-month closure. His boast of subjecting the island to agrarian reform was another shocker, as data from the Department of Agrarian Reform showed that there was no land under agrarian reform coverage in Boracay. DAR officials from the national office had to rush to the island to conduct an ocular inspection to search for patches of land to distribute.

On the eve of the closure itself, there was still no executive order, proclamation, or any official document from the Palace laying down the legal basis for what was turning into a lockdown. Details were murky on the rehabilitation plan or the supposed assistance to be given to around 50,000 workers and residents dependent on the island's tourist industry.

Apparently, the various national agencies involved – the environment, tourism, local government, public works, labor, and social welfare and development – were formulating plans on the fly, trying to fit in with Duterte's rant-turned-policy. The confusion was evident and certainly felt on the ground. Many asked: was the closure simply a pretext to facilitate the construction of a big casino complex on the island? Was it a ploy to wipe out the little guys and allow the bigger players to cash in on the island's huge tourism industry?

Through it all one thing was certain: the impending, albeit temporary, dislocation and loss of livelihood of thousands in and out of the island.

Disregarding the stakeholders

Most stakeholders and even Duterte's Cabinet officials had recommended fixing Boracay's problems step by step, dealing first with the non-compliant establishments. It was suggested that the demolition of illegal structures and the construction or expansion of sewage and wastewater facilities be done in 3 or 4 phases, with each phase requiring a corresponding closure only of the affected portion of the island.

Closure was always considered a last resort and, if ever, was to be done during the lean tourist season between June to November. The main consideration was the social and economic costs of such a move.

A 6-month closure would simply be too costly. The government itself projected a loss of ₱18 billion-P20 billion worth of gross receipts from tourism. Industry players estimated the figure could go as high as ₱30 billion, with an estimated 700,000 bookings by foreign tourists cancelled.

But more than the figures would be the impact on the island's residents, employees and service providers. Boracay's tourism industry employs around 35,000 service workers coming from as far as Mindanao and Luzon. The loss of jobs alone would be catastrophic for families dependent on their daily income from Boracay.

In addition to this, Boracay's closure would have a dire impact on the regional economy and provincial government services. 45% of the provincial government's income for health and social services comes from taxes, fees, and licenses generated from the island. Electricity consumers in the region would have to shoulder the additional cost of Boracay's unused contracted power supply. The country's economic managers predicted a 5.7% decline in the region's gross domestic product due to the 6-month closure.

In the end, Duterte decided that such social and economic costs were secondary to the need to rehabilitate Boracay at the quickest possible time. Stakeholders, including local government officials, resort owners, residents and workers were never consulted on the closure. Sober calls for a partial closure or rehabilitation in phases, articulated even by a number of Cabinet members, were eventually ignored. (READ: INSIDE STORY: How Duterte decided on Boracay closure)

Duterte's rant had opened the door to giving government absolute control and unhampered operations in the island. Closing Boracay would bring business activity to virtually zero, greatly reduce the population, and control movement in the island, giving the regime a free hand to do whatever it wanted but at great cost to so many people.

Overkill

As if this was not enough, government's takeover of Boracay was emphasized by the vivid sight of armed police conducting mock crowd control and anti-terrorism operations on the island's glistening white sand, even as Coast Guard and Navy assets patrolled its sparkling waters. There were even attack helicopters. For this to happen on an island paradise was simply shocking and mind boggling.

In fact, Boracay is such a benign place. There has never been any terrorist attack or threat in Boracay. Activist groups are practically non-existent. There are no labor unions or mass organizations. Resort owners and business establishments are actually supportive of the rehabilitation efforts, with many demolishing their illegal structures on their own.

And yet there they were: 630 additional police personnel, elite Navy SEAL units and naval crafts, Air Force and Coast Guard patrols “protecting” Boracay like in a Bourne Identity movie. What was the threat? Where was the enemy? Nobody knew. It was all for show. (WATCH: Gov't simulates terror attack, hostage-taking in Boracay)

The Duterte way

The Boracay closure follows the familiar pattern of Duterte's approach to addressing complex crisis situations.

Step 1 is to exaggerate the problem: the country is turning into a narco-state, terrorists are taking over Mindanao, Boracay is a cesspool.

Step 2 is to create straw men: 4 million drug-crazed addicts, ISIS and communist terrorists, greedy resort owners and leftist agitators.

Step 3 is to propose a dramatic, out-of-the-box solution: kill the drug addicts and pushers, bomb Marawi, declare martial law over the entire Mindanao, and close down Boracay.

Step 4 is to show political resolve at the expense of human rights and the rule of law: commend and reward perpetrators of extrajudicial killings, extend martial law for another year and intensify military operations in Mindanao, send in the cavalry to threaten and intimidate those affected by Boracay's closure.

Step 5 is to redistribute the spoils: the Davao Group, Chinese contractors in Marawi, Chinese casino and resort operators in Boracay.

This approach plays on popular sentiment and public cynicism of institutions and processes, relies heavily on police and military action, projects Duterte as a tough, no-nonsense leader, and enriches his own set of cronies and sycophants. It's a formula taken out of every strongman's rule book. – Rappler.com