Furor erupted last week over a new World Bank report showing another huge drop in the Philippines' global ranking when it comes to ease of doing business.

For 16 years now, the World Bank has been publishing its annual Doing Business report, which ranks countries according to their business friendliness. The 2019 edition was published end of October.

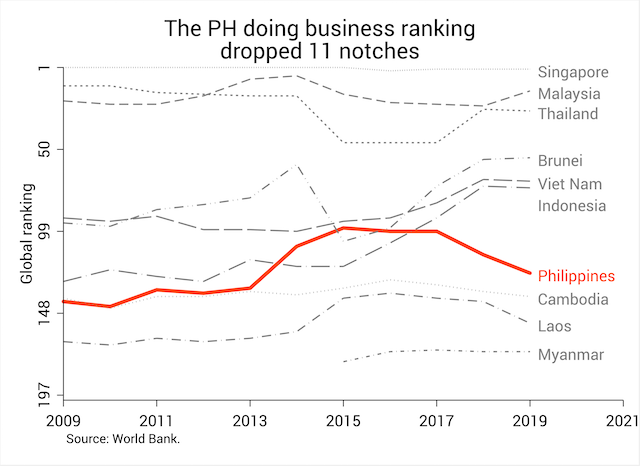

Figure 1 below shows the global ranking of countries in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) in recent years. On one extreme you have Singapore, often the world's most business-friendly economy. On the other extreme you have Myanmar, which ranked 171st out of 190 economies in 2019.

What's so controversial about the report concerns the Philippines: from 113 this year, we dropped to rank 124 in 2019 – an 11-notch drop. The year before we also dropped by an even larger 14 notches.

Hence, under President Rodrigo Duterte's watch, we've gone down the global Doing Business ranking by 25 notches all in all – by far the largest decline in ASEAN.

Notice that instead of converging with the ASEAN leaders, we're inching closer to the region's laggards – Cambodia, Laos, and Myanmar.

Figure 1.

Lagging behind

What explains the country's plummeting rank?

To rank the different countries, the Doing Business report assigns each economy a score which supposedly summarizes – in one number – how easy it is to do business there. The higher the score the better.

Over the past 3 years the Philippine score has been falling steadily: from 60.40 in 2017, 58.74 in 2018, to 57.68 in 2019. But why?

In the latest data, one aspect jumps out in particular: "getting credit." In just one year our ranking here dropped by a whopping 42 notches.

This drop is so huge that it's now the subject of a formal complaint to the World Bank filed by President Duterte's economic managers. They claim that the World Bank failed to gain access to the country's largest credit database, thereby "grossly" understating the extent of credit coverage in the country.

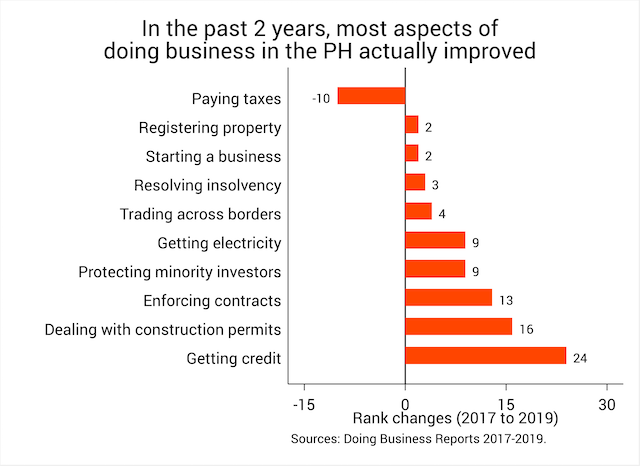

This, however, cannot be the whole story. Figure 2 below shows that over the past two years our "getting credit" ranking actually improved by 24 notches, even as our overall ranking dropped.

In fact, all other aspects of doing business in the Philippines – from dealing with construction permits, enforcing contracts, to starting a business – saw improved ranks over the past two years (except "paying taxes" where our rank dropped by 10 notches).

This suggests that other economies have made larger strides in minimizing the costs of doing business. The Philippines is becoming less and less business friendly in relative terms.

Figure 2.

Worse business climate

Our deteriorating competitiveness is corroborated by other statistics.

Figure 2 shows the recent slump in both consumer and business confidence. Business owners, in particular, expressed concerns about runaway inflation, the implementation of tax reform, the weakening peso, and tighter supply of raw materials.

Figure 3.

There is also a generally higher degree of uncertainty in the Philippine business climate today, brought in no small measure by President Duterte's blatant "weaponization" of laws and regulations against certain businesses and industries.

Aside from this, many businesses are spooked by the prospect of sweeping reform measures currently being pushed by the government, including comprehensive tax reform and federalism via charter change.

For instance, the Tax Reform for Attracting Better and High Quality Opportunities (Trabaho) bill is a sequel of sorts to the original tax reform package called the Tax Reform for Acceleration and Inclusion (TRAIN).

Trabaho basically aims to do two things: lower the corporate income tax rate to 20% (in a staggered manner), and recover the lost revenues from that by imposing stricter rules in the granting of fiscal incentives (like income tax holidays).

Many companies – especially those located in the country's economic zones – are threatening to leave because of Trabaho and relocate to other countries like Malaysia and Vietnam which are offering far more attractive and accessible incentives.

If credible, Trabaho might undermine the country's already faltering competitiveness and business friendliness.

One study in the information technology-business process outsourcing sector estimates revenue losses to the tune of $3.5 billion to $5.5 billion (from 2018 to 2022) once Trabaho pushes through. This could result in 160,000 to 250,000 job losses in that industry alone.

Meanwhile, a group of semiconductor firms estimates they will have to lay off as many as 140,000 workers, again on account of Trabaho.

At this point, of course, these are mere threats which do not necessarily predict well whether these firms will actually leave the country once Trabaho is enacted.

But is this a risk the government is willing to gamble now, considering the alarming decline of our global Doing Business ranking?

Trabaho means "job" in Filipino, and a Trabaho bill that could result in so many job losses is not just supremely ironic, it also reinforces the burgeoning notion that doing business in the Philippines is going to be harder still.

Just do your homework

The country's deplorable ranking in the latest Doing Business report was made extra embarrassing by the fact that President Duterte just signed the Ease of Doing Business Act in late May 2018.

The new law aims to expedite transactions of businesses with the government, implement the use of a single form for various permits and clearances, establish "one-stop shops" for businesses in each local government unit, and automate all business permit applications, among other things.

To be sure, this new law is a very welcome development, one that could reverse our sad performance in recent Doing Business reports.

Neither should the blame be entirely placed on the Philippine government. The World Bank's Doing Business report is highly controversial, and not a few countries and international organizations have challenged its methods over the years.

In fact, one of this year's Nobel laureates resigned as chief economist of the World Bank earlier this year due in part to the alleged politicization of past Doing Business reports.

Nonetheless, rather than rant about the World Bank's methodologies, perhaps the best response by the Duterte government is to just do their homework and make the Philippines as business-friendly as possible.

No doubt the Duterte government is already friendly to certain business interests, especially those originating from Davao City and China.

On Wednesday, November 7, the consortium between Udenna Corporation (owned by Davao City tycoon Dennis Uy) and China Telecom provisionally won its bid to become the country's 3rd telecommunications company and rival the present duopoly.

But the Philippine economy does not hinge on Davao City and China alone.

Can we rely on Duterte to remove his biases and extend his unabashed friendliness to all other businesses as well? – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).