As always, the devil is in the details.

Amid high inflation (6% as of November), many people expect the pending Rice Tariffication Bill to be a source of quick relief.

Some government economists estimated that the law, once passed, might slash the price of rice by as much as P7 per kilo, thus tempering runaway inflation.

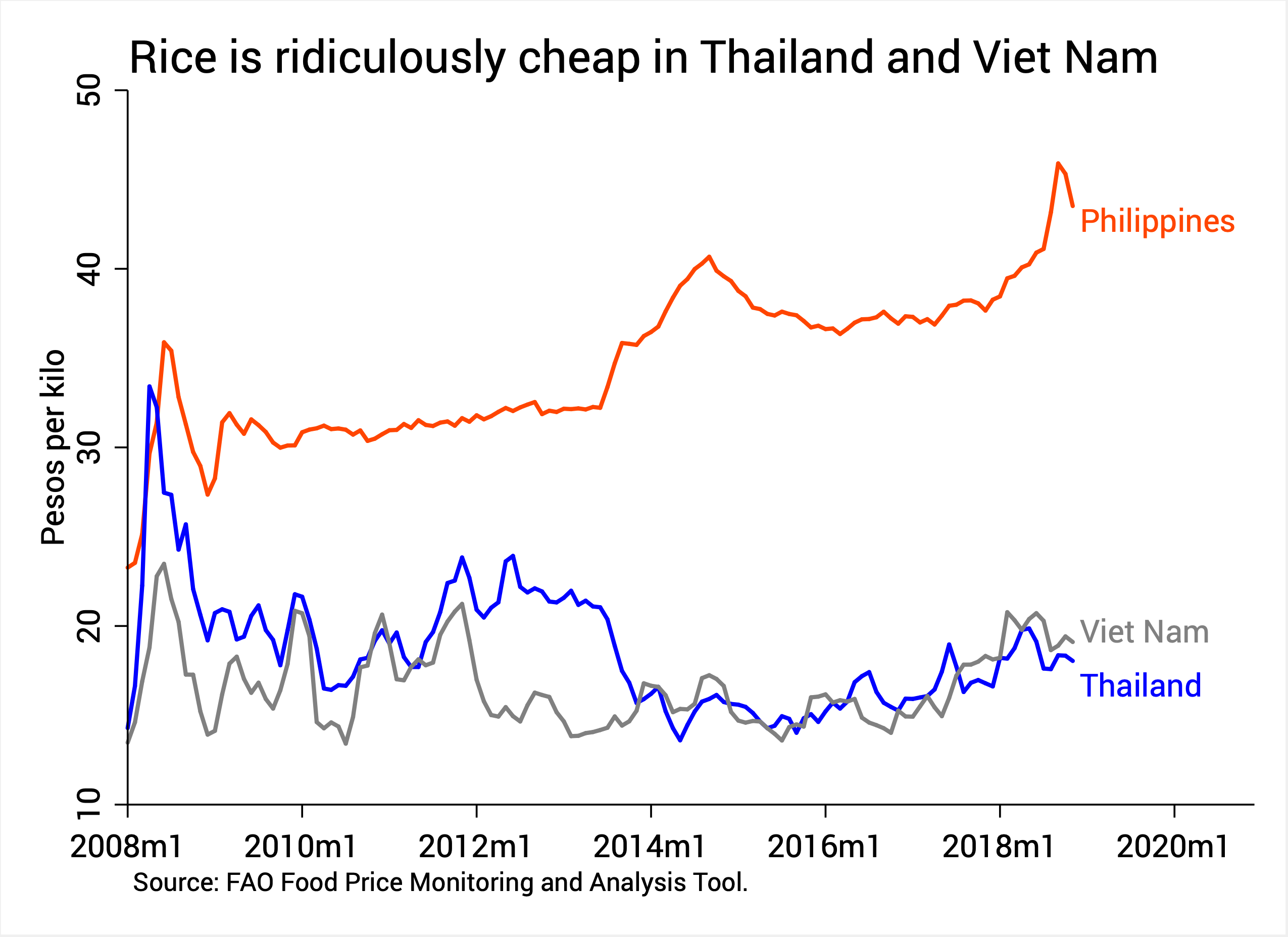

By allowing freer importation of rice, economists also expect the law to allow Filipinos to enjoy somewhat the ridiculously low rice prices in countries like Thailand in Viet Nam (see Figure 1).

Whereas rice in the Philippines costs more than P40 per kilo (on average), it costs less than P20 per kilo in Thailand and Viet Nam.

Figure 1.

The Rice Tariffication Bill has gone through both houses of Congress now, and is nearly up for signature by President Duterte.

But in this article I discuss why the current form of the law leaves much to be desired, despite the much-needed rice reforms it brings.

Overdue

The truth is we’ve been putting off rice tariffication for decades.

For the longest time, importing rice in the Philippines has been controlled by one government agency: the National Food Authority (NFA), and its predecessor the National Grains Authority (created by ex-president Ferdinand Marcos in 1972).

This import monopoly allows the NFA to bring rice into the country based on its projections of rice demand and supply nationwide. However, over the years, miscalculations have often led to over- or under-importation (thus, rice surpluses and shortages).

Since the country joined the World Trade Organization (WTO) in 1995, we’ve committed to put an end to these import quotas and “tariffy” them instead – that is, convert them into their equivalent tariffs or import taxes.

When we say “equivalent,” we mean we apply tariff rates that bridge the difference between local and world rice prices.

But this international commitment to liberalize the rice sector posed a threat to Filipino farmers.

The Philippine government has since postponed its compliance with the WTO several times. In 1994 we asked for an extension until 2005, then another until 2012, and yet another until 2017.

Sure, these extensions were permitted by the WTO, but only on condition that the government will allow the private sector to import rice within a certain quota, slapped with a tariff rate.

From 59,730 metric tons in 1995 (with a 50% tariff), this quota is now up to 805,000 metric tons in 2018 (with a 35% tariff).

Finally, in 2016, the economic managers prevailed upon President Duterte to finally abolish these rice import quotas. (READ: Rice in the time of Duterte: Will more imports be good?)

Caveats

Now, with the Rice Tariffication Bill, we’re closer than ever to putting an end to these interminable deadline extensions.

However, there are caveats.

First and foremost, this bill sets a 35% tariff rate on all rice imports from ASEAN countries, and a 50% tariff on all imports from non-ASEAN countries.

But some experts say these tariff rates are still too high, and lower rates (say, to the tune of 10% to 20%) might be more in keeping with the overarching goal of making rice more affordable for Filipinos.

Second, apart from paying these tariff rates, the bill requires that all private players secure “sanitary and phytosanitary import clearances” from the Bureau of Plant Industry (BPI) before they can import.

This is to ensure that the rice they’ll import will not be infested by pathogens or pests like bukbok (weevils).

Although this sounds reasonable enough, past experience tells us that this could be prone to abuse – as rightly pointed out by Dr Ramon Clarete of the UP School of Economics.

Remember the abnormal increase of garlic prices in 2014? Investigations found that it was borne by colluding BPI officials who issued sanitary and phytosanitary permits to select garlic cartels.

The whole point of rice tariffication is to abolish the licensing system that prevailed in the past. But this provision in the Rice Tariffication Law creates what is effectively another import license – albeit in the guise of health permits. Does the Rice Tariffication Bill have enough safeguards against their abuse?

Third, the Rice Tariffication Bill also introduces a Rice Competitiveness Enhancement Fund (Rice Fund) that earmarks P10 billion annually for 6 years, sourced from the rice tariff revenues.

This Rice Fund is supposed to shield Filipino rice farmers from the influx of competition from abroad, and bolster their competitiveness by furnishing them with more farm equipment, enhanced skills, and better seed varieties.

But again, we have to be wary of what happened in the past: similar funds had miserably failed to improve the plight of our farmers. Some were even outright corrupted.

Remember the heinous Fertilizer Fund Scam, where P728 million worth of Department of Agriculture funds meant to buy fertilizers for farmers were just funneled to the 2004 presidential campaign of ex-president Gloria Macapagal Arroyo?

Dr Emil Q. Javier of the National Academy of Science and Technology has also warned that the free distribution of inputs the Rice Fund entails (including machinery or seeds) is “well-meaning but misdirected.”

For him, the Rice Fund will be put to better use if it were focused instead on improving rice farmers’ access to credit and crop insurance.

The Rice Fund also does not address deeper problems in the agricultural sector, such as the failure of the country’s land reform program and the inability of small farmers to consolidate their landholdings and exploit the cost savings borne by “economies of scale.”

All in all, absent sufficient safeguards, the Rice Fund might only serve as another costly leaky bucket that politicians can exploit.

Let’s manage our expectations

The path to hell is paved with good intentions, and the Rice Tariffication Bill is no exception.

To be sure, its heart is in the right place. Not only does it promise to lower rice prices, abate inflation, and fulfill our decades-old commitment to tariffy rice quotas, it also allocates funds for the betterment of our rice farmers.

Yet with import license permits that could be abused and a juicy P10-billion pot of money that could be mismanaged, the jury is still out whether the Rice Tariffication Bill will really live up to its promise.

Let’s manage our expectations accordingly. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).