I was in Florida, thousands of miles away from Paris, yet I couldn't escape the shock and the sadness of what was unfolding in front of the television screen: terror attacks in six separate locations around the city; 130 dead and scores of others injured. The ominous superstitions attributed to Friday the 13th had become all too real for Parisians and the rest of the world.

All of a sudden, it wasn't an out-of-sight-out-of-mind type of situation, anymore – especially because I was preparing to fly to Paris in a few days.

I arrived with my sister and our American friend in Paris three days after the attacks. Charles de Gaulle Airport, touted to be among the busiest airports in the world, was largely vacant save for a few travelers, airport employees, and the occasional group of soldiers strolling the airport facilities.

In a taxi on our way to downtown Paris, I expected dozens of checkpoints along our path and troops marching the streets, but to my surprise, everything appeared normal. There were plenty of vehicles on the roads, the shops were open, and the people were out and about — openly defying the government's orders to stay indoors.

Joie de vivre

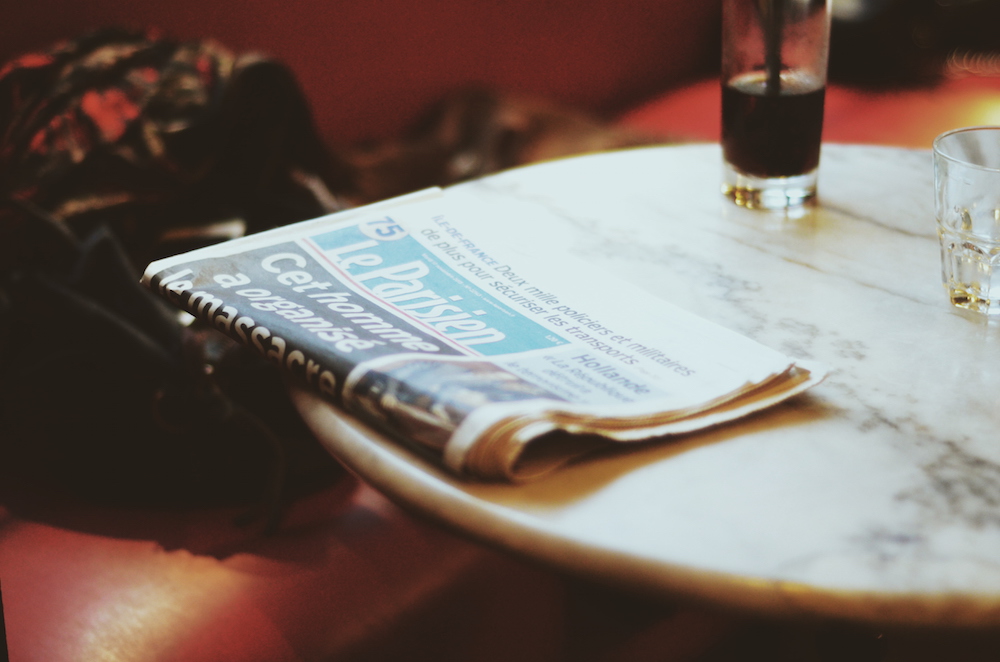

We stopped at a small cafe called Le Petit Louis and enjoyed some hot chocolate while waiting for our Airbnb host. There was a group of three young friends sitting beside our table, engaged in a casual conversation over half-empty drinks and a folded Le Parisien newspaper on the table.

Its headline read: Cet Homme a Organise Le Massacre (This Man Organized the Massacre), referring to the attack's ring leader, Abdelhamid Abaaoud.

The cafe's bartender sat by one of the empty tables near the girls, lighting small candles. I asked him if it was for the victims of the attacks. He chuckled and told me they were in fact meant for the dinner tables.

I noticed the girls at the other table looking at us. I turned to them and asked about how they felt about the recent tragic events. One of them who introduced herself as Lauren, revealed to me that she lost four of her friends during the attacks. “I was sad, but we also have to live, you know?” she told me. (READ: Longtime Bataclan owner wants show to go on after Paris attacks)

“If we are afraid, the terrorists will win. The answer is Joie de Vivre, the joy of life.” She smiled with a subtle sense of defiance. (READ: Paris attacks: 'We were targeted because we love life')

It didn't take long before I witnessed firsthand how the Parisians practice what they preach when Lauren's friends Vy, Lolita, and Dany the bartender joined in for a lively exchange of silly stories punctuated by bad jokes and genuine laughter.

No 'cure-all'

While hanging outside the cafe, I struck up a more serious conversation with a French-Tunisian woman. She was in Tunisia when a lone gunman opened fire at tourists at a popular beach resort in Port El Kantaoui.

I asked her if she supported President Hollande on waging war against Daesh – the Arabic acronym of ISIS which many Europeans prefer to use – and she told me France should have waged a war on Syria a long time ago, when the terror group's influence in the region was still limited.

Her perspective, however, is just one among many opinions that currently divide the French people on the ISIS and Syria debate. While many demand swift retaliation against ISIS especially in Syria, some people believe that it is dangerous to think a military strategy is a cure-all solution for this complicated crisis.

After all, it is difficult to wage a war against an unconventional enemy that has no established front lines and is driven by an ideology that transcends geographic borders.

Not quite business as usual

The next morning, I woke to Atika Shubert on CNN counting the explosions heard in an apartment complex during a police operation in Saint-Denis, a suburb in Paris where some of the terror suspects, including Abaaoud, were hiding.

While the news made everyone outside of Paris susceptible in thinking that the entire city was in a state of hysteria, the rest of Paris went on with their daily lives. People outside our apartment walked in quick strides as they hurried to work, oblivious to the media barrage in Saint-Denis. Out of sight, out of mind.

Apart from the Saint-Denis incident, everything actually seemed normal that day despite the presence of soldiers carrying high-caliber weapons and police cars at all the major tourist spots.

We felt like regular tourists and we had almost forgotten that Paris was still in a state of emergency. Everything appeared to be business as usual around Paris – but not quite.

French flags flew at half mast all over the city. The Louvre was open, but it didn't have the notorious lines of visitors it's usually known for. Place De la Concorde was filled with various groups of middle-aged Chinese tourists pouring out of buses, lining up for group photos, and proving the benefits of community Tai Chi by doing impressive jump shots in front of the Place's Ferry's wheel.

Notre Dame seemed to have a considerable amount of visitors, but apparently not enough for the restaurants in the area struggling to find customers. The Lover's Bridge was practically empty except for a few curious visitors, and a busking couple singing a passionate love song in English and French to an invisible audience.

The Eiffel Tower, closed the previous day, was reopened and was perhaps the busiest among the places we visited that day. There were walking tours, illegal vendors selling Eiffel key chains, and a lot of tourists on the lawn in front of the tower making poor attempts at selfies and forced perspective shots.

At Place de la République

It was a fun day, yet, the idea of being a cheerful backpacker traveling in a country still recovering from a tragedy felt insensitive and selfish to me.

I had a strong urge to spend some time with the mourning people of Paris and that the only way for me to justify my travel to France was to prioritize my visit to Place de la République – the unofficial memorial for the victims of the Charlie Hebdo massacre, and more recently, the Friday the 13th attacks.

We arrived at the Republique Station during rush hour and the area was busy with commuters eager to get to their next destination. The memorial was in the middle of a busy roundabout, yet it had a very solemn atmosphere.

Conversations were hushed while people prayed. There were parents watching their kids writing messages and drawing figures on the pavement with colored chalk. There were people lighting candles and even grown men silently crying. There were journalists with cameras constantly hunting for the next front page photo, and reluctant subjects ignoring the loud clicks while praying in peace.

There were also tourists taking selfies with their camera phones, eager to tell the world about the tragedy of Paris along with the irony of their grinning faces on Instagram.

I walked with my sister and our American friend to the base of the monument where people left hundreds of flowers and candles for the victims and I began to pray, asking for world peace – the most unlikely, most unrealistic request I ever wished the heavens for, but for once, I meant it.

Love vs. the 'Piecemeal Third World War'

Pope Francis has called this disparate conflict the Piecemeal Third World War. Although we may not fully acknowledge it yet, it is already being waged within ourselves. Religious fundamentalism has succeeded in inciting hatred in people.

I can feel real divisions in opinions even between those closest to me. On Facebook alone, I see messages and posts full of hostility and bigotry toward other people all the time —and yes, they're from my friends and family, and probably yours, too.

As we made our way to the other side of the monument, we stumbled upon a group of Muslim women holding white roses while calling for war against Iran and Syria.

I wanted to listen to what they had to say, so I squeezed my way into the circle and listened closely to the group's speech: “We ourselves have been victims of this brutal repression,” the spokesperson declared in front of the cameras and curious onlookers.

“Millions of our brothers, sisters, are youngsters who have been exploited in Syria, in Iraq, in Iran, because of repression. We are the same voice of defending freedom, of defending justice, of defending democratic value. We need to be behind each other. We need to be united, with one voice to stand firm against terror.”

Calling for unity has never been more important to the vilified French Muslims who are facing times of uncertainty in their own country. Despite having the largest Muslim population in Europe, France has been subjecting its Muslim community to varying forms of religious oppression and discrimination for many years now.

Some argue France's heavy-handed treatment of Muslims has (and probably still continues to) lead some people to become radicalized. After a series of terror attacks just this year, many French Muslims are fearing reprisals and even more discrimination against their community.

There is also great concern among the Muslim community that the far-right political parties all over Europe including France's National Front, led by Marine Le Pen – a politician who is openly anti-Islam and anti-immigration – are gaining a lot of momentum.

While I was waiting for an opportunity to talk to the women, my sister dragged me out of the crowd. Our American friend was spooked by what was happening and wanted to leave. I intended to stay longer, but I was forced to go with them.

The new normal

While on a train going back home, I was trying to reason with my sister to allow me to return to the Place when a voice on the public address (P.A.) system made an announcement in French.

It initially sounded routine, but in the background we could hear tense radio chatter that made us wonder what was going on. “Excusez-moi, parlez-vous Anglais?” I asked the lady seated in front of us. She was curiously studying us earlier while my sister and I were having our little discussion in Bikol.

She promptly stood up, grabbed on to the pole we were holding on to and told us in a calm voice: “There is panic in Liberté station and people are running. They are going to stop train operation until it is safe.”

And there it was—my first real glimpse of the “new normal." I felt a strange mix of emotions that included fear, confusion, paranoia, defiance, and I-have-to-go-home. There was an eerie silence on the train. Everyone seemed calm, and so was I.

But as a matter of fact, my nostrils were stretched to take in more air. I began to wonder if the next wave of terror attacks had finally begun. After a few moments of suppressed panic, the P.A. finally announced the train was safe to proceed again.

The woman told us she was sorry that we had to experience such an incident while in Paris, which I found rather strange. I asked her why and she said people in Paris were a little bit on the edge, but that life had to go on.

She continued to say that she was happy that we decided to visit the city despite of all that was happening because it helped give Parisians like her a sense of normalcy. When she arrived at her station, she waved us goodbye and disappeared into the crowd.

Quite frankly, I do not remember much about the places I visited in Paris. But, I still vividly remember the brief moments I had with the people I met there. I also still remember the wonderful moods the City of Light gave me, despite being in the middle of one of the darkest chapters in its recent history.

I can see now that peace is such a very delicate thing to maintain – even in the land of liberty, equality, and fraternity. All the moral progress we have made as a human race is currently under a test. It is up to us to remember the things history has taught us not to ever repeat, or revert to the old prejudices we've been fighting so hard all these years to eradicate.

For the most part, France has so far chosen to stay united as a people despite their fears and differences. Here's to hoping they'd continue to actively choose to do so. Here's to hoping the rest of the world would choose to do so. – Rappler.com

Chad Verzosa is a freelance writer currently based in Tampa, Florida. To view examples of his work, you can visit his website.