Last week the Philippine Statistics Authority (PSA) brought us a string of surprisingly good economic news.

Not only did the country’s unemployment and underemployment rates dip to 14-year lows, but poverty also saw a significant drop from 2015 to 2018. Simply put, fewer Filipinos are poorer and jobless now.

These numbers – especially the poverty stats – were met by a mixture of relief and disbelief.

On the one hand, Representative Joey Salceda said the numbers only show “Dutertenomics is working” (whatever Dutertenomics means nowadays). On the other hand, Gabriela, a group fighting for women’s rights, called the government’s poverty report a “tall tale.”

Setting aside politics, these numbers are objectively good. But what brought them about? And can we trust them?

Good jobs figures

Figure 1 shows the downtrend of unemployment and underemployment since 2005.

To be considered unemployed in the Philippines, you need to satisfy 3 criteria: you must have no work, you must be looking for work, and you must be available to work.

As of October the unemployed among those aged 15 and older reached an all-time low of 4.5%. That means there are just over two million unemployed Filipinos now, about 153,000 fewer than last year.

Figure 1.

Although lower unemployment is heartening to hear, some scholars think unemployment is a poor measure of welfare. Most poor Filipinos are, in fact, employed. They cannot afford to be indefinitely without any work, however menial or low-paying.

A better welfare measure could be the underemployment rate, which comprises all those with work but don’t earn enough or still want to work more hours.

Figure 1 shows that underemployment, too, dropped to a 14-year low of 13% last October.

Should we credit the Duterte administration for these rosy figures?

First, both unemployment and underemployment – despite jagged ups and downs – have generally been on the downtrend since 2005. You might say it’s just a matter of time these figures reached new historic lows.

Second, if you add unemployment and underemployment, you will see a downtrend that roughly matches the “joblessness” data independently collected by the Social Weather Stations or SWS (see Figure 1).

The SWS’ joblessness data serves as a check on government figures. Although both unemployment and underemployment went down this year, SWS’ joblessness rate – for some reason – did not.

Third, the jobs record of the Duterte administration has not been particularly impressive. Up until last year, the Aquino administration created jobs 10 times faster than the Duterte administration. (READ: Jobs, jobs, jobs: Where, where, where?)

It’s only since the second quarter of this year that job creation picked up in earnest.

Sizable drop in poverty

Equally if not more impressive is the fact that poverty substantially went down from 2015 to 2018 (Figure 2).

PSA reported last week that poverty incidence – the share of the population considered poor – dropped from 23.3% to just 16.6%. That’s a considerable 6.7 percentage point drop.

This means from almost one in 4 Filipinos, only one in 6 is now poor. This translates to nearly 6 million Filipinos lifted out of poverty in just 3 years (or about two million a year).

Meanwhile, the share of Filipino families considered poor similarly went down from 17.9% to just 12.1%. This means there were almost a million fewer poor families in 2018 than in 2015.

Figure 2.

As with unemployment and underemployment, you might think poverty is due to go down anyway.

But the drop from 2015 to 2018 is the fastest in recent memory, notwithstanding the upward adjustment of 2015 poverty figures you see in Figure 2 (owing to recalculations).

This is worth celebrating. Some take it to mean that the incomes of the poor are becoming more responsive to the overall growth of the economy. But some caveats are in order.

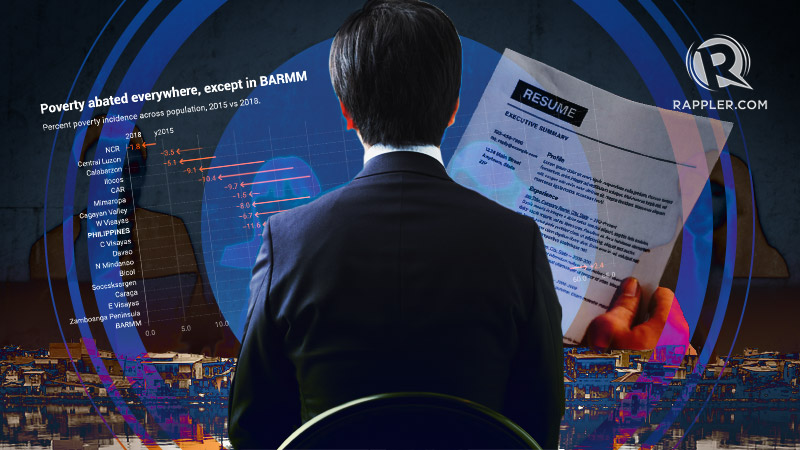

First, poverty abated in most regions of the country, especially Northern Mindanao, Bicol, and Central Visayas (Figure 3). But poverty actually worsened in BARMM, and poverty reduction in Cagayan Valley was negligible.

Moving forward, government must make sure growth lifts all boats, and no region is left behind. Inclusivity is key.

Figure 3.

Second, as I noted in a previous piece, we need to update the way we count the number of poor Filipinos. (READ: How well are we measuring PH poverty?)

Right now, for instance, the government considers poor everyone whose income falls below P71.50 a day. But Gabriela deemed this poverty line “ridiculously low given the ever rising cost of living in the country.” Perhaps it’s time for a thorough review of poverty lines nationwide.

The current poverty estimation method also focuses too much on counting Filipinos who don’t earn enough incomes. But poverty goes well beyond having inadequate incomes: you can also be poor in other dimensions of life, such as education or health.

For this reason, other countries also pay attention to multidimensional poverty rather than just income poverty.

To its credit, the PSA has officially started measuring multidimensional poverty. But the results of these studies must also be highlighted if we are to get a fuller picture of poverty in the Philippines.

Third, several policies of the Duterte administration have shoved some of our people deeper into poverty rather than pulled them out of it.

For instance, before being appointed National Statistician, Dr Dennis Mapa, who used to be dean of the UP School of Statistics, wrote a paper claiming runaway inflation last year likely caused about a million Filipinos to fall below the poverty line.

This finding was corroborated by separate studies of the Philippine Institute for Development Studies, the government’s public policy think tank. (READ: How the TRAIN law worsened poverty, inequality)

Recall that prices accelerated last year partly because of the excise taxes introduced and hiked by the 2017 TRAIN law.

There’s also recent research suggesting Duterte’s war on drugs may be negating the government’s social protection programs, notably the Pantawid Pamilyang Pilipino Program or 4Ps. (READ: How Duterte’s drug war is negating key anti-poverty programs)

Therefore, it’s entirely possible poverty would have dropped even more had it not been for these pernicious, ill-advised policies and their impacts.

Issue of trust

The question remains: Can we trust these numbers?

Notwithstanding the room for improvement in the way our government collects statistics, the PSA’s numbers are wholly trustworthy.

I’ve worked with PSA officials and staff before in my previous stint in government, and they’re some of the most professional in the bureaucracy. Under the leadership of the National Statistician, I’m also confident the PSA will be immune to any political pressure that may come its way.

This is not to say we should be complacent. Apart from the need to constantly improve our data collection, unemployment and poverty rates in the Philippines are still stubbornly high relative to our ASEAN neighbors.

But in the meantime, let’s celebrate the good economic news. God knows we don’t get a lot these days. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD candidate at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Follow JC on Twitter (@jcpunongbayan) and Usapang Econ (usapangecon.com).