This is the condensed version of the lecture entitled, “Weaponizing Lawfare in the Philippines,” delivered at Plenary IV: Combatting Lawfare: Strategies and Responses of the “International Forum on Lawfare: Weaponization of Lawfare vs Democratic Dissent” at the Teresa Yuchengco Auditorium, De La Salle University on February 21, 2020.

During the Marcos reign of power, I worked closely with Walden Bello to organize a session of the Permanent Peoples Tribunal in Brussels, which carefully documented the crimes of the Marcos government as perpetrated against the citizenry of the country. The proceedings of the tribunal produced a devastating record of abuse of state power.

The international attention generated by this extralegal action helped prepare the atmosphere for what later became the People Power Movement of the 1980s – a civil society initiative that exposed the abusiveness of government, especially when conventional means of judicial redress were unavailable.

Lawfare in wartime US

The assault on fundamental rights raises profound concerns about the future of democracy. In the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, national security discourse in the United States became a battleground for contesting ideas about how lawfare was used and misused. National security hawks contended that according due process protection to those suspected of terrorist activities was the type of lawfare that interfered with national security imperatives. In sharp disagreement, civil libertarians invoked law and civil rights to oppose and denounce the demonization of Muslims and the denial of their rights.

It should be recalled that the mass internment of Japanese who were legally residing in the West Coast, for alleged national security reasons at the start of World War II after the Pearl Harbor Attacks, was a fundamental abuse of individual rights to due process by the US Government. When the US Supreme Court upheld such abuse, it lent its legal authority and prestige to this negative instance of lawfare.

These departures from the rule of law in wartime, are however, less serious than the tactics employed by autocratic leaders seeking to stifle dissent and discredit opposition during normal times. These tactics are more dangerous because, if successful, they will, as they often have, engulf all branches of government – disabling democracy all together. It excuses no one – however prominent. It intimidates more than it punishes – pacifying society as a whole at the very time when the citizenry needs to be mobilized to protect the integrity of a political system that safeguards rather than punishes citizen participation, which necessarily includes dissent and opposition.

Lawfare at present

Around the world, the rise of the infamous leaders of the new world – Trump, Modi, Bolsonaro, Erdogan, and Duterte, is the new phenomenon of democratic electoral procedures elevating and sustaining anti-democratic leaders despite using their official positions to repress, and ignoring constitutional limits on their authority. The growing support for this type of leaders – who obstruct and punish persons found in the opposition – endangers the rule of law.

They employ similar strategies: distortion of normal legal practice with tactics involving deliberate manipulations of law and government procedures to cripple opposition politics. They pave the way for the erosion and subversion of the vital independence of legislative and judicial institutions.

The rise to power of these leaders ominously warns us that even in long established political democracies, opportunistic politics can, and will, overwhelm constitutional protections against abuses of State power.

Lawfare is today’s threat to democracy

When a leader views criticism not as part of the essential give-and-take of a political democracy, but rather as an impermissible assault on his leadership, it reduces political leadership to a menacing call for unquestioning obedience on the part of citizens. In this instance, the law does not serve its proper role of protecting citizens against State abuses, but rather functions as an instrument of naked power deployed against notable critics and opposition figures. It becomes a weapon of the powerful, used to avenge legitimate attacks – where even elected members of legislative and judicial institutions are commanded to obey, or expect harmful consequences.

Lawfare as manipulated by unscrupulous leaders is a global challenge that has become a threat not only to democracy, but also to the structure of government based on checks and balances, to the dignity of individual citizens, and to the independence of persons elected to serve in government.

Lawfare should not only be uncritically condemned when used regressively, and its deployment to deny basic rights should likewise be unconditionally exposed, opposed, and rejected. Considering that lawfare has a positive potential when properly deployed in the pursuit of justice, it is important to distinguish between the contradictory roles of lawfare – as repressive and as emancipatory.

Lawfare is regressive when it criminalizes opposition – regardless of legitimacy. A current example can be drawn from the recent European and North American experience – where hate speech or anti-Semitism criticism of Israel’s policies and practices is criminalized.

It is progressive when the law offers a remedy. One such instance is when Palestine sought recourse from the International Criminal Court to investigate allegations of Israeli criminality.

Lawfare against De Lima

Senator Leila de Lima is the most prominent victim of the partisanship propagated by Duterte. She was removed as Chair of the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights in a very apparent retaliation for accusing Duterte of introducing policies of unlawful extra-judicial execution. She has been attacked in unspeakably vulgar terms by Duterte partisans in language that was nothing short of a vicious form of character assassination.

This partisanship having been utilized in weaponizing the law has deprived Senator de Lima of the opportunity to fully serve the people who elected her to office, denied her the right to vote on legislative issues, and participate in debates. But more dangerously, it has set a precedent – having made it so easy to attack a sitting Senator, any such attack on the people of the Philippines is no longer far-fetched. Coming to her aid then, will rescue not just a single individual, but will likewise restore confidence that the rule of law can function under the altered conditions of political democracy in the Philippines.

What is to be done?

Any act to subdue and put an end to regressive lawfare would depend largely on whether the deviation from adherence to the rule of law is partial, exceptional, and seems reversible. In this case, maximum effort should be made to make intelligent use of formal legal procedures as provided.

The crucial role that media and academic experts can play – complementary to the efforts of professional lawyering – bears stressing. Media coverage and engagement of academic experts will expose the political nature of any misuse of law – which will arouse a responsive public opinion. Such extra-legal pressure in a political system that maintains its claims of democratic legitimacy, can be effective in persuading wavering judges and conformist legislators to do the right thing, and at least refrain from doing the wrong thing. But it will be more challenging where government institutions have been repeatedly subverted, where the independent media has been eliminated or cowed into submission, and where protest activities are met by harsh police tactics.

The prolonged detention and framing of Senator De Lima is a shocking reminder of how abuses of power occur in a country that claims to be a constitutional democracy. It represents the distorted application of law and the manipulation of basic institutions of government. Her case is an extreme example of law gone wrong – a pattern of injustice being challenged to the extent possible by lawyers, but this may not be enough. Progressive lawfare, enlisting support of nationally and internationally respected NGOs, encouraging the preparation of a public report on abuse of rights and regressive lawfare, filing allegations via Special Rapporteurs of the UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, should be under consideration and explored if further attempts to render justice on behalf of Senator de Lima do not succeed. Autocratic leaders after all, are allergic to procedures that document their abuses and crimes, and pass judgment based on the conscience of moral authority figures, testimony of victims, and opinions of legal experts. – Rappler.com

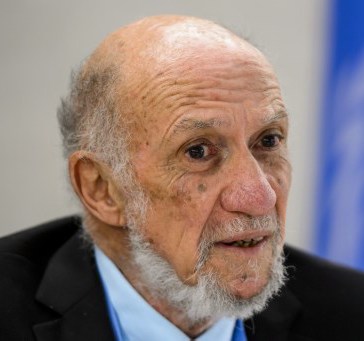

Professor Richard Anderson Falk is Albert G. Milbank Professor Emeritus of International Law at Princeton University, and Visiting Distinguished Professor in Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara who authored and co-authored several books. He received his BS from the Wharton School, University of Pennsylvania; LLB. from Yale Law School; and JSD. from Harvard University.

In 2001, he served on a 3-person Human Rights Inquiry Commission for the Palestine Territories that was appointed by the United Nations, and previously, on the Independent International Commission on Kosovo. He serves as Chair of the Nuclear Age Peace Foundation's Board of Directors, and as honourary vice-president of the American Society of International Law. He also acted as counsel to Ethiopia and Liberia in the Southwest Africa Case before the International Court of Justice.

In March 2008, the United Nations Human Rights Council appointed Falk to a 6-year term as a UN Special Rapporteur on Palestinian human rights.