Editor's note: A longer version of this article was first published on Medium on March 20, 2020. It is being reposted with the author's permission. Watch and read the transcript of his interview with Rappler's Maria Ressa.

READ: Part 1 | [ANALYSIS] Strategies for fighting COVID-19

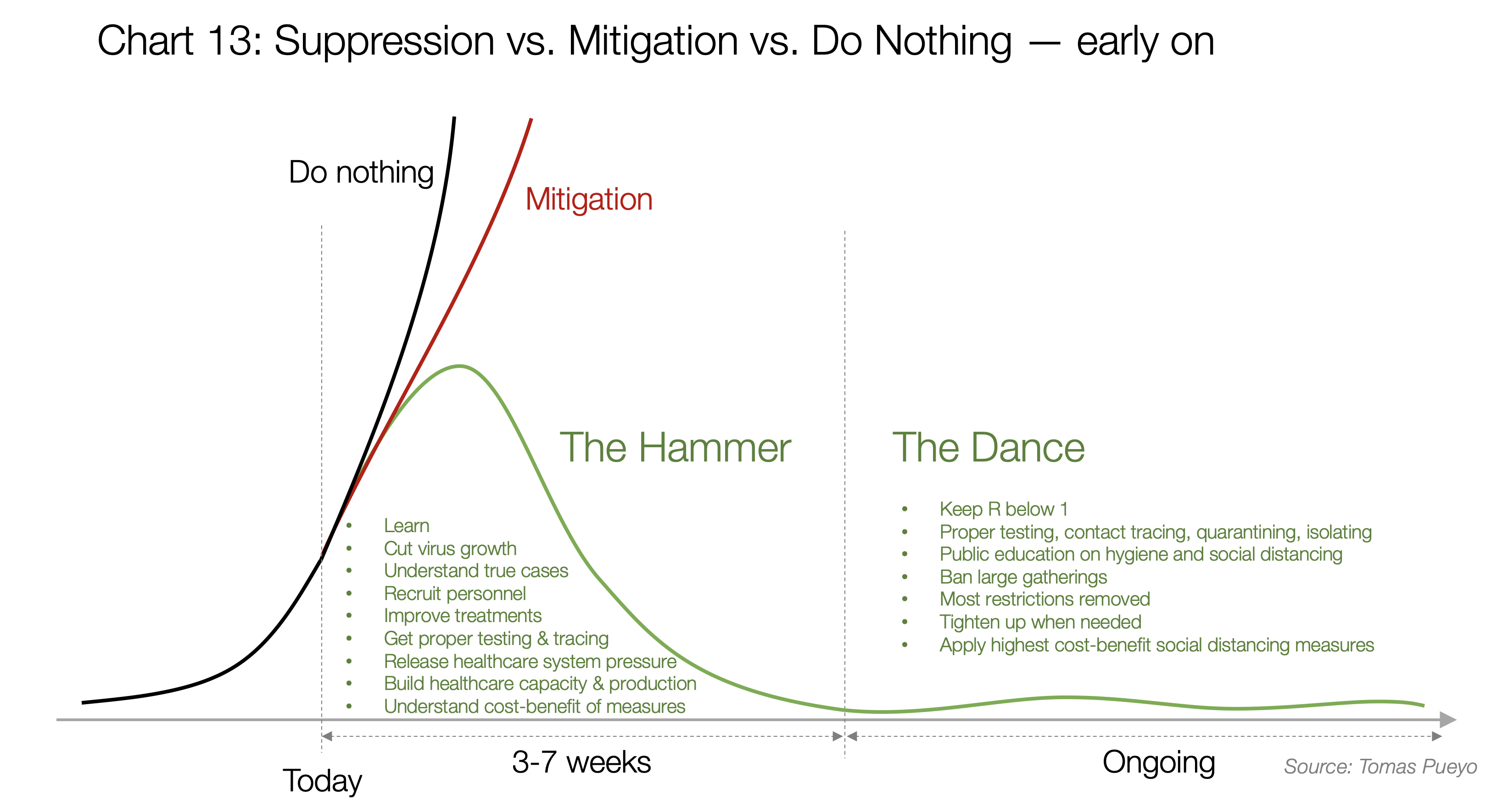

Now we know that the mitigation strategy is probably a terrible choice, and that the suppression strategy has a massive short-term advantage.

But people have rightful concerns about this strategy:

- How long will it actually last?

- How expensive will it be?

- Will there be a second peak as big as if we didn’t do anything?

Here, we’re going to look at what a true suppression strategy would look like. We can call it "the hammer and the dance."

The hammer

First, you act quickly and aggressively. For all the reasons we mentioned above, given the value of time, we want to quench this thing as soon as possible.

One of the most important questions is: how long will this last?

The fear that everybody has is that we will be locked inside our homes for months at a time, with the ensuing economic disaster and mental breakdowns. This idea was unfortunately entertained in the famous Imperial College paper:

Do you remember this chart? The light blue area that goes from end of March to end of August is the period that the paper recommends as the hammer, the initial suppression that includes heavy social distancing.

If you’re a politician and you see that one option is to kill hundreds of thousands or millions of people with a mitigation strategy and the other is to stop the economy for 5 months before going through the same peak of cases and deaths again, these don’t sound like compelling options.

But this doesn’t need to be so. This paper, driving policy today, has been brutally criticized for core flaws: they ignore contact tracing (at the core of policies in South Korea, China or Singapore, among others) or travel restrictions (critical in China), ignore the impact of big crowds...

The time needed for the hammer is weeks, not months.

This graph shows the new cases in the entire Hubei region (60 million people) every day since January 23. Within two weeks, the country was starting to get back to work. Within 5 weeks it was completely under control. And within seven weeks the new diagnostics was just a trickle. Let’s remember this was the worst region in China.

Remember again that these are the orange bars. The gray bars – the true cases – had plummeted much earlier.

The measures they took were pretty similar to the ones taken in Italy, Spain or France: isolations, quarantines, people had to stay at home unless there was an emergency or they had to buy food, contact tracing, testing, more hospital beds, travel bans… They were, however, more strict: for example, people were limited to one person per household allowed to leave home every 3 days to buy food. Also, their enforcement was severe. It is likely that this severity stopped the epidemic faster, but the current lockdowns in Europe are likely to have a similar result, even if not as fast.

Can we stay home for a few weeks to make sure millions don’t die? I think we can. It depends on what comes next, though.

The dance

If you hammer the coronavirus, within a few weeks you’ve controlled it and you’re in much better shape to address it. Now comes the longer-term effort to keep this virus contained until there’s a vaccine.

This is probably the single biggest, most important mistake people make when thinking about this stage: they think it will keep them home for months. This is not the case at all. In fact, it is likely that our lives will go back to close to normal.

The dance in successful countries

How come South Korea, Singapore, Taiwan, and Japan have had cases for a long time – in the case of South Korea thousands of them – and yet they’re not locked down home?

In this video, the South Korea foreign minister explains how her country did it. It was pretty simple: efficient testing, efficient tracing, travel bans, efficient isolating, and efficient quarantining.

This paper explains Singapore’s approach. Want to guess their measures? The same ones as in South Korea. In their case, they complemented them with economic help to those in quarantine and travel bans and delays.

Is it too late for other countries? No. By applying the hammer, you’re getting a new chance, a new shot at doing this right.

But what if all these measures aren’t enough?

The dance of R

I call the months-long period between the hammer and a vaccine "the dance" because it won’t be a period during which measures are always the same harsh ones. Some regions will see outbreaks again, others won’t for long periods of time. Depending on how cases evolve, we will need to tighten up social distancing measures or we will be able to release them. That is the dance of R: a dance of measures between getting our lives back on track and spreading the disease, one of economy vs. healthcare.

How does this dance work?

It all turns around the R. If you remember, it’s the transmission rate. Early on in a standard, unprepared country, it’s somewhere between 2 and 3: during the few weeks that somebody is infected, they infect between 2 and 3 other people on average.

If R is above 1, infections grow exponentially into an epidemic. If it’s below 1, they die down.

During the hammer, the goal is to get R as close to zero, as fast as possible, to quench the epidemic. In Wuhan, it is calculated that R was initially 3.9, and after the lockdown and centralized quarantine, it went down to 0.32.

But once you move into the dance, you don’t need to do that anymore. You just need your R to stay below 1. And you can do a lot of that just with a few simple measures.

Detailed data, sources and assumptions here

This is an approximation of how different types of patients respond to the virus, as well as their contagiousness. Nobody knows the true shape of this curve, but we’ve gathered data from different papers to approximate how it looks like.

Every day after they contract the virus, people have some contagion potential. Together, all these days of contagion add up to 2.5 contagions on average.

It is believed that there are some contagions already happening during the “no symptoms” phase. After that, as symptoms grow, usually people go to the doctor, get diagnosed, and their contagiousness diminishes.

For example, early on you have the virus but no symptoms, so you behave as normal. When you speak with people, you spread the virus. When you touch your nose and then open the door knob, the next people to open the door and touch their nose get infected.

The more the virus is growing inside you, the more infectious you are. Then, once you start having symptoms, you might slowly stop going to work, stay in bed, wear a mask, or start going to the doctor. The bigger the symptoms, the more you distance yourself socially, reducing the spread of the virus.

Once you’re hospitalized, even if you are very contagious you don’t tend to spread the virus as much since you’re isolated.

This is where you can see the massive impact of policies like those of Singapore or South Korea:

- If people are massively tested, they can be identified even before they have symptoms. Quarantined, they can’t spread anything.

- If people are trained to identify their symptoms earlier, they reduce the number of days in blue, and hence their overall contagiousness.

- If people are isolated as soon as they have symptoms, the contagions from the orange phase disappear.

- If people are educated about personal distance, mask-wearing, washing hands, or disinfecting spaces, they spread less virus throughout the entire period.

Only when all these fail do we need heavier social distancing measures.

The ROI of social distancing

If with all these measures we’re still way above R=1, we need to reduce the average number of people that each person meets.

There are some very cheap ways to do that, like banning events with more than a certain number of people (eg. 50, 500), or asking people to work from home when they can.

Others are much, much more expensive, such as closing schools and universities, asking everybody to stay home, or closing bars and restaurants.

This chart is made up because it doesn’t exist today. Nobody has done enough research about this or put together all these measures in a way that can compare them.

It’s unfortunate, because it’s the single most important chart that politicians would need to make decisions. It illustrates what is really going through their minds.

During the hammer period, they want to go as low as possible while still remaining tolerable. In Hubei, they went all the way to 0.32. We might not need that: maybe just to 0.5 or 0.6.

But during the Dance of the R period, they want to hover as close to 1 as possible, while staying below it over the long term.

What this means is that, whether leaders realize it or not, what they’re doing is:

- List all the measures they can take to reduce R

- Get a sense of the benefit of applying them: the reduction in R

- Get a sense of their cost: the economic and social cost.

- Stack-rank the initiatives based on their cost-benefit

- Pick the ones that give the biggest R reduction up until 1, for the lowest cost

This is for illustrative purposes only. All data is made up. However, as far as we were able to tell, this data doesn’t exist today. It needs to.

Initially, their confidence in these numbers will be low. But that‘s still how they are thinking – and should be thinking about it.

What they need to do is formalize the process: understand that this is a numbers game in which we need to learn as fast as possible where we are on R, the impact of every measure on reducing R, and their social and economic costs.

Only then will they be able to make a rational decision on what measures they should take.

Conclusion: Buy us time

The coronavirus is still spreading nearly everywhere. 152 countries have cases. We are against the clock. But we don’t need to be: there’s a clear way we can be thinking about this.

Some countries, especially those that haven’t been hit heavily yet by the coronavirus, might be wondering: is this going to happen to me? The answer is: it probably already has. You just haven’t noticed. When it really hits, your healthcare system will be in even worse shape than in wealthy countries where the healthcare systems are strong. Better safe than sorry, you should consider taking action now.

For the countries where the coronavirus is already here, the options are clear.

On one side, countries can go the mitigation route: create a massive epidemic, overwhelm the healthcare system, drive the death of millions of people, and release new mutations of this virus in the wild.

On the other, countries can fight. They can lock down for a few weeks to buy us time, create an educated action plan, and control this virus until we have a vaccine.

Governments around the world today, including some such as the US, the UK, Switzerland, or Netherlands have so far, as of writing, chosen the mitigation path.

That means they’re giving up without a fight. They see other countries having successfully fought this, but they say: “We can’t do that!”

What if Churchill had said the same thing? “Nazis are already everywhere in Europe. We can’t fight them. Let’s just give up.” This is what many governments around the world are doing today. They’re not giving you a chance to fight this. You have to demand it. – Rappler.com

*Tomas Pueyo is a Silicon Valley entrepreneur and behavioral psychologist who specializes in exponential growth. He wrote the Medium post, "Coronavirus: Why You Must Act Now," which was read by tens of millions of people around the world.

READ Pueyo's previous work:

- [ANALYSIS] How many cases of COVID-19 will there be in your area?

- [ANALYSIS] COVID 19: The difference in death rates

- [ANALYSIS] Strategies for fighting COVID-19