The events of the last few weeks have engendered much goodwill towards the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte at the same that it has triggered apprehensions about where it is headed. (READ: Duterte's decision-making unpredictable)

The events of the last few weeks have engendered much goodwill towards the administration of President Rodrigo Duterte at the same that it has triggered apprehensions about where it is headed. (READ: Duterte's decision-making unpredictable)

Hopes

The naming and shaming of 5 former and current police generals for their alleged involvement in the drug trade was only the most dramatic in a series of moves by the new president that elicited popular approval.

Hopes for a new social dispensation were stirred by several fast-moving events, among them a promise that the administration would end contractualization and an announcement that an executive order would institutionalize Freedom of Information. That a new deal was at hand for the marginalized sectors appeared imminent with the appointment of people associated with the National Democratic Front (NDF) to the top posts in the Department of Agrarian Reform, Department of Social Welfare and Development, and the National Anti-Poverty Commission.

Perhaps the appointment that drew the most applause from civil society was that of anti-mining advocate Gina Lopez as head of Department of the Environment and Natural Resources. Civil society also cheered when Mr Duterte blasted Lopez’s critic, mining magnate Manny Pangilinan, as “just a puppet of the foreign based Salim Group, while I am the chosen president of the Republic of the Philippines!”

Indeed, we seem to be entering not simply a new presidency but a new era.

Fears

Hopes, however, have mingled with fears. The spate of killings of suspected drug pushers and users triggered suspicions that crooked cops were getting rid of their accomplices or that they were acting on the green light to kill drug pushers and addicts with no or minimal attention to due process that they feel they had gotten from the president.

Words matter, said human rights advocates, worried that Duterte’s statements prior to his ascent to the presidency that citizens had the right to kill drug pushers if they resisted and his offering a higher bounty for dead rather than living criminals might already have inaugurated a wave of vigilantism that might claim innocent lives. This could easily degenerate, they said, into people settling scores with their enemies simply by branding them as pushers.

The numbers are grim: according to the Philippine Association of Human Rights Advocates (PAHRA), there have been 163 killings since the May 9 elections, most but not all of them in violent encounters with the police.

The curious conjunction of moves that apparently promote economic and social rights with advocacy of extrajudicial killings has provoked two interesting responses. One is that we should not dwell too much on the president’s endorsement of extrajudicial killings or violations of due process since he is, after all, committed to taking measures that will advance the social and economic welfare of the marginalized masses. The second response is that what matters are not individual rights but “class rights,” and we should not bother too much with the “so-called rights” of people that belong to the exploiting classes and the criminal class or “lumpenproletariat.”

These views are worrisome. For one, the so-called social and economic reforms are still promises, and it may were well happen that they could be blocked or diluted by compromises with vested interests. But this is not the principal reason why these views are wrong and dangerous.

To focus first on the second response, one has only to recall the so-called “Ahos (‘Garlic’) Campaign” that ravaged the ranks of the left during the 1980’s to realize the terrible consequences of such a stance. Some 2000 people were killed with no regard for due process simply because they were arbitrarily branded as class enemies or “agents of the ruling class.” Although this view is now held by a distinct minority of progressives, its continuing influence in some sectors of the left must not be underestimated.

The first response – that we should give the President some leeway in his methods of dealing with crime since he is, after all, supportive of social and economic reform – is very popular. In fact, one can say that a very large number of those who voted for Duterte voted for him because they approved of his extreme measures to curb crime, along with his promise to root out corruption and his strong condemnation of poverty and inequality.

Now, given the poor record of previous administrations on law and order, one can certainly understand why people are fed up with and support drastic measures on crime and drugs. But the popularity of Duterte’s law and order stance does not make it right. One can definitely agree with Duterte supporters that the administration of justice is terrible, with too many crooks evading the law, but it is quite another thing to say that the way to deal with them is via extrajudicial execution and skipping due process altogether.

Fundamental rights and positive rights

When he first signaled his intention to run for the presidency last year, I said that Duterte’s candidacy would be good for democracy because it would force liberals and progressives to defend a proposition that they had long taken for granted: that human rights and due process are core values of Philippine society.

Let us now address this urgent task.

The right to life, right to freedom, right to be free from discrimination, and right to due process have often been called fundamental rights because they assert the intrinsic value of each person’s existence and underline that this value is not bestowed by the state or society. They are also often called “negative” rights or “inalienable” rights to stress that other individuals, corporate bodies, or the state have no right to take them away or violate them.

What have now come to be known as “positive rights” such as the right to be free from poverty, the right to a status of economic equality with others, and the right to a life with dignity are those rights that promote the attainment of conditions that allow the individual or group to develop fully as a human being. Positive rights – sometimes referred to as social, economic, and cultural rights – build on negative or fundamental rights. The recognition and institutionalization of fundamental rights may have been historically prior to the recognition and achievement of positive rights but the latter are necessary extensions of the former. Rights, in short, are indivisible, and positive rights have a fragile foundation in a state where the basic right to life is negated by leaders who claim to be promoting them.

Liberal democracy vs authoritarian rule

One of the key functions of the state is to secure the life and limbs of its citizens, but this must be accomplished while respecting the full range of rights of its citizens. There is a necessary tension between not violating individual rights and achieving security and political order. This healthy tension is what distinguishes the liberal democratic or social democratic state from the authoritarian, fascist, Stalinist, or ISIS state.

To progressives and liberals, recognition and respect for human, civil, political, social, economic, and cultural rights have been a fundamental thrust in the evolution of the Philippine polity, a process that has been influenced by landmark events in the history of democracy such as the French Revolution and the later struggles against colonialism, fascism, and Stalinism. Individual rights have been won in interconnected global struggles against ruling classes, imperial oppressors, corporations, and bureaucratic and military elites. This historical process has produced polities called liberal democracies and social democracies, the latter being distinguished by their greater stress on the achievement of the full range of positive rights, including universal social protection.

However, one must acknowledge that there has been a counter-thrust, one that has periodically emerged to challenge the primacy of the individual and human rights. This perspective places the state as the authority or arbiter of what “rights” the individual can enjoy, subordinates the welfare of the individual citizen to the security or needs of the state, and says that due process is principally one determined by the needs of the state and not by respect for the rights and welfare of the individual. This historical counter-thrust became dominant during the martial law period from 1972 to 1986 and it threatens to become dominant today, with support from a significant part of the citizenry.

The perils of Dutertismo

Currently, President Duterte embodies the view that refuses to recognize the universality of rights and denies due process to certain classes of people in the interest of combating crime and corruption. The majority of those who voted for him agreed with his stance. They form the social base of Dutertismo, a movement based on mass support for a leader who personifies the illiberal, extreme measures they feel is necessary to deal with crime, corruption, and other social problems.

At the risk of repeating ourselves, let us make 3 points with respect to this trend.

First, we do not question the goal of fighting crime. Indeed, we support it. But it cannot be achieved by trampling on human rights. No one has the right to take life except in the very special circumstance and in a very clear case of self-defense. Everyone is entitled to the enjoyment of those rights and their protection by the state. And if these rights must be limited for the greater good, then there must a legally sanctioned process to determine this. Wrongdoers must certainly be meted punishment, but even wrongdoers have rights and are entitled to due process.

Second, denying some classes of people these rights, as Duterte does, puts all of us on the slippery slope that could end up extending this denial to other groups, like one’s political enemies or people that “disrupt” public order, like anti-government demonstrators or people on striking for better pay. In this connection, remember that candidate Duterte threatened to kill workers who stood in the way of his economic development plans and made the blanket judgment that all journalists who had been assassinated were corrupt and deserved to be eliminated. That was no slip of the tongue.

Third, rights are indivisible. Measures that purportedly promote positive rights and advance the economic and social welfare of citizens rest on a fragile basis and can easily be taken back if they are not recognized as stemming from and resting on the basic right to life. Upholding positive rights while negating fundamental rights involves one not only in a logical but in a very real contradiction. To say I will liberate you from exploitation but hold your life hostage to your “good” behavior involves one in a contradiction that is ultimately unsustainable; this is the contradiction that unravelled the Stalinist socialiist states of Eastern Europe.

Strategic opposition

The President’s campaign and his program were driven by his depreciation of human rights and due process. There is a fundamental political cleavage in the country between those who support his views on human rights and due process and those opposed to them. Thus those of us who consider human rights and due process as core values cannot but find ourselves in strategic opposition to this administration.

Being in opposition does not mean denying the legitimacy of the administration. It means recognizing the legitimacy conferred by elections but registering disagreement with the central platform on which it was won, that is, the control of crime and corruption not through the rule of law but mainly through extrajudicial execution and violation of due process.

It is always difficult to be in opposition to a popular administration. This is why one must commend proven human rights stalwarts like Rep Teddy Baguilat and Edcel Lagman, who have stood up for principles and declared themselves in the minority or opposition even as the vast majority of their partymates in the Liberal Party jumped en masse into the Duterte bandwagon after the election to share in the spoils of the man they had opposed. More than their erstwhile comrades, Baguilat and Lagman know that popularity is fleeting, and it is not worth going against your principles to accommodate it.

But with the disintegration of a viable opposition in the House and Senate, the unpredictable posture of the Supreme Court, and silence in the bureaucracy (with the notable exception of the Commission on Human Rights), it becomes imperative that civil society must become the central locus of opposition.

Opposition does not mean total opposition. It means critical opposition, whereby one may support positive legislative measures proposed by the administration even as one maintains a strategic opposition to it owing to its violation of one’s core values and principles. In short, one should definitely support measures such as agrarian reform, an end to contractualization, institutionalization of the freedom of information, and the phasing out of mining, for these are progressive measures that can only redound to the welfare of society and the environment. But fundamental rights are fundamental rights, and since these basic rights are threatened by the philosophy and politics of the current administration, then one must stand strategically in opposition to it even as one supports its measures that enhance people’s positive rights.

Defense of one’s core values, however, is not the only reason for being in opposition. The existence of a strong opposition is the best defense of democracy, for nothing more surely leads to the dismantling of democracy than the concentration of power. In this regard, we believe the president when he says that he has no intention of remaining in power beyond 6 years. But, if we have learned anything from politics, it is that good intentions can easily be corrupted by absolute power. Paradoxically, the best way we can help President Duterte keep his promise is to provide him with a vigorous opposition.

In sum, a strong opposition based on the defense of universal human rights is the best way to ensure the future of Philippine democracy. – Rappler.com

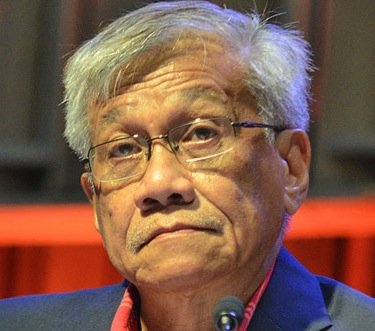

Walden Bello served as a member of the House of Representatives from 2009 to 2015. He broke with the Daang Matuwid Coalition of President Benigno Aquino III and gave up his seat in the House in March 2015 in what is regarded as the only resignation on principle in the history of the Philippine Congress.