Although national attention is currently focused on the war on drugs, the Duterte administration is quietly making gains in another policy area – rice policy.

Although national attention is currently focused on the war on drugs, the Duterte administration is quietly making gains in another policy area – rice policy.

Recently the Duterte Cabinet, led by its economic team, agreed to lift restrictions on the importation of rice by 2017. This would usher in greater volumes of rice imports that the government has been trying to put off for more than two decades now.

On the one hand, local rice farmers are naturally worried. They say that this policy will hurt them in the same way that other farmers have been hurt by the influx of cheap imported agricultural goods (like onions).

On the other hand, some say that this policy will help promote competition, lower prices, and benefit several millions of Filipino rice consumers.

Some groups are already hailing the Cabinet’s rice policy as one of its first major economic reforms. To appreciate how exactly this policy can benefit the country in general, it may help to step back and look at key facts about rice consumption and production in the Philippines.

How affordable is rice in the PH?

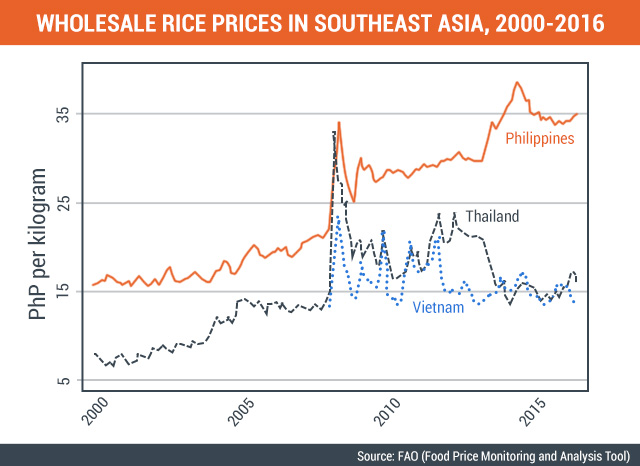

Figure 1 shows that the Philippines has always had some of the highest rice prices in Southeast Asia. As of August 2016, Filipinos are paying more than twice for a kilo of rice compared to their Thai and Vietnamese counterparts.

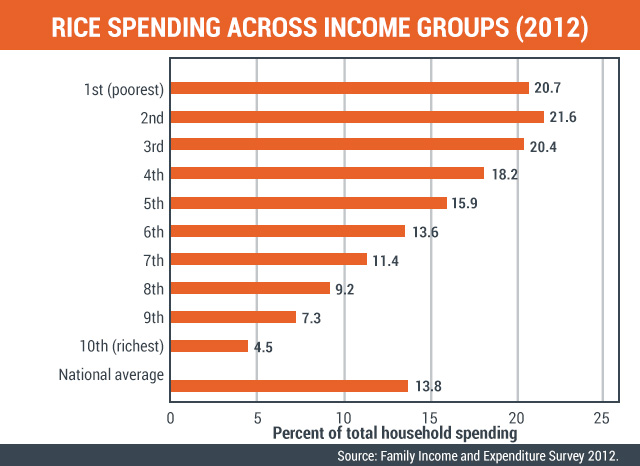

These high rice prices harm poor Filipino households more than anyone else. Based on recent data, while the poorest households spend around 20% of their income on rice alone, the richest households spend just under 5% (Figure 2).

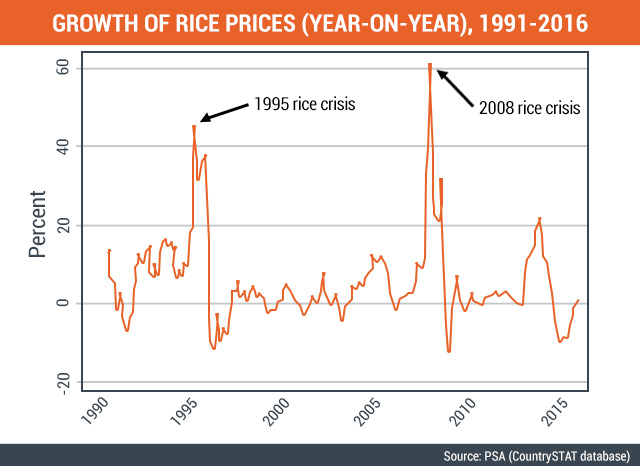

Rice prices are harmful not only when they are high, but also when they are volatile. Figure 3 shows that since 1991 we experienced three major spikes in rice prices: 1995 (a 45% increase in price prices), 2008 (60% increase), and 2014 (20% increase).

Such significant jumps in rice prices can have devastating impacts on the poor. A 2015 study found that at the height of the 2008 rice crisis, the inflation rate faced by the poorest 30% of the population was about twice the inflation rate faced by the general population. This significantly eroded the purchasing power of the poor and led more households into hunger and poverty.

Some studies also show that poor rice farmers are, in fact, net consumers (rather than net producers) of rice, meaning that they consume more rice than they produce. Hence, poor farmers are hurt by high rice prices as well.

What makes rice extra expensive for Filipinos?

High and volatile rice prices in the Philippines are borne by a myriad of factors, but largely geography and policy.

On the one hand, the Philippines has a relative disadvantage when it comes to rice production because of our peninsular geography. Unlike Vietnam and Thailand, we do not enjoy as much vast, uninterrupted rice plains and access to natural irrigation at the scale of, say, the mighty Mekong River.

On the other hand, expensive rice is also due to government policies, particularly the National Food Authority’s (NFA) status as the sole importer of rice in the country.

Every year the NFA decides how much rice to import in a given year based on forecasts of domestic rice demand and supply. This heavy-handed tinkering with the market, however, can occasionally lead to disaster when planning becomes faulty.

Specifically, the NFA may at times fail to import sufficient quantities of rice, leading not only in smuggling (which is really a manifestation of a large unmet demand for rice) but also in catastrophic shortages and price spikes.

Our last two rice crises attest to this. In 1995 and 2008, erroneous supply forecasts, external factors, and badly-timed imports led to massive rationing and queues. These were relieved only through belated importation of massive amounts of rice.

In the aftermath of these events, a select number of private agents have been allowed to import rice, but with a collective limit of 805,000 metric tons per year and levied with 35% tariff rates.

It is these import restrictions that the Duterte Cabinet is seeking to abolish by next year. By allowing more private agents to import rice, the NFA need not second-guess domestic demand and supply conditions, thus avoiding over- or under-importation of rice in any given year.

More importantly, this policy also means more competition in the domestic market that could lead to lower and less volatile prices, as well as food security for the vast majority of Filipinos.

This is not to say, however, that the NFA no longer has any significant role to play. For instance, it could focus on maintaining a buffer stock of rice to prepare for emergency shortfalls and provide immediate relief to avoid events like the violent Kidapawan protests last March. The NFA could also maintain a small tariff from which it can earn revenues to support farmers adjusting to this new era of freer rice trade.

Conclusion: Good rice policy as a low-hanging fruit

The Duterte Cabinet’s proposal to lift rice import restrictions promises to benefit millions of Filipino rice consumers, especially the poor.

However, rice producers have already protested the Cabinet’s recent pronouncements. There are even renewed calls to reestablish the NFA’s status as the sole importer of rice. Hence, the Duterte Cabinet’s success in bringing rice policy reforms is yet to be ensured.

Such policy could arguably enjoy more success if it found support in the President himself. After all, there are about 101 million rice consumers in the country. In contrast, there are just 1.8 million drug users in the country as of 2015. Hence, shifting even a bit of attention away from drug policy and into rice policy can potentially benefit a far greater number of Filipinos.

Of course, it seems that the current drug war is here to stay. But given the potential benefits, here’s hoping that the present leadership brings at least as much interest and enthusiasm into rice policy. In the vast tree of social policies, this could very well be one of the lowest-hanging fruits out there. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD student at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations. Thanks to Kevin Mandrilla (UP Asian Center) and Ammielou Gaduena (UP School of Economics) for valuable comments and suggestions.