There seems to be some confusion about the economic impact of the peso’s recent depreciation against the dollar. Depending on who you listen to, the peso’s 7-year low would seem to be disastrous at worst or beneficial at best.

There seems to be some confusion about the economic impact of the peso’s recent depreciation against the dollar. Depending on who you listen to, the peso’s 7-year low would seem to be disastrous at worst or beneficial at best.

On the one hand, the President compounded public fears last Tuesday when he said, “Ina-undermine tayo ng mga Amerikano ngayon. They are manipulating na ang peso raw ay bumababa.” (The Americans are now undermining us. They are manipulating the peso to depreciate it.)

On the other hand, the government’s economic managers have taken a more sober stance. Budget Secretary Diokno allayed investors’ concerns by saying that the depreciation is “no cause for concern”. Finance Secretary Sonny Dominguez even claimed that the economy might even benefit from a “slightly weak” peso.

What’s really happening to the peso, and should we be worried or not? First, let’s review the facts and put things in perspective.

Perspective

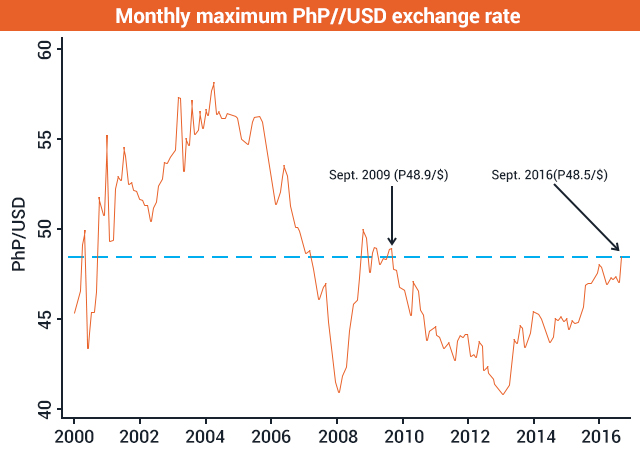

Figure 1 below confirms that the peso slumped to a 7-year low this week. The last time the nominal exchange rate reached P48 per US dollar was in 2009 at the height of the global economic crisis. Note, however, that the peso has been generally depreciating since 2013.

The same data also suggest that the recent depreciation is nowhere near the massive swings in the peso’s value seen over the past 15 years. Figure 2 shows that the peso’s slump this September represents a small blip compared to its massive appreciation in 2007-2008 or its similarly massive depreciation in 2008-2009 at the height of the global economic crisis.

Not bad per se

The peso’s recent depreciation is not only relatively small, but also not bad per se. In fact, certain sectors can indeed benefit from it. To see this, let’s go back to what “depreciation” and “appreciation” mean.

When the peso “depreciates” (say, from P45 to P50 per US dollar), Filipino goods and services become cheaper in the eyes of foreigners, boosting the sales of the economy’s dollar-earning sectors which constitute as much as 40% of the economy, according to the finance department. These include exports, tourism, and BPOs, as well as OFWs (overseas Filipino workers) whose remittances take on larger values, thus increasing the purchasing power of their families back at home.

On the other hand, when the peso “appreciates” (say, from P45 to P40 per US dollar), Filipino goods and services become more expensive in the eyes of foreigners. Consequently, foreign goods become cheaper in the eyes of Filipinos, who then have greater capacity to purchase more foreign goods. It is in this sense that a peso appreciation is often quoted by the media as a “strengthening” of the peso.

Overall, a sizeable proportion of the country’s population stands to benefit from the peso’s depreciation. This episode of depreciation may also benefit the country on the whole, given that our global competitiveness ranking has slipped by 10 notches from last year.

Some have correctly pointed out that the recent depreciation could also mean that the country will have to pay more for its foreign debts. While true, this would be worrisome only if the peso continuously depreciates in the coming weeks and months.

A symptom of capital flight?

Perhaps a greater cause of concern is whether the peso’s depreciation is a symptom of capital flight – that is, an exodus of financial assets. There are two factors at play here.

First, some say that the peso’s slump is due to the US central bank’s impending announcement of raising their interest rates by the end of 2016, which implies greater returns for US investments. When investors sell their financial assets in the Philippines to invest in the US, they need to exchange their peso assets back into dollars. This floods the currency market with pesos and lowers the price of pesos in terms of dollars – hence, a depreciation.

Second, some argue that the peso’s slump is also due to investors’ increasing worries about doing business in the country. The President’s unpredictable and incendiary statements, his conflicting foreign policy, the internecine drug war, and the rise of extrajudicial killings – all these tend to turn off investors. Thus, when they sell their domestic assets, this similarly floods the market with pesos and further depreciates the peso. (READ: Duterte: I’m being portrayed as a ‘cousin of Hitler’)

Which factor holds more water? Thankfully, some indicators point to the former rather than the latter.

For instance, it’s true that the Philippine Stock Exchange (PSE) saw a continuous net foreign selling of stocks since mid-August – meaning that for 6 weeks straight, foreign stock investors have sold more stocks than they have bought.

But Figure 3 shows that the sell-off seems to have peaked in early September and has already reversed this week. Could this indicate that the worst is over? Only time will tell.

What about the President’s claim of currency manipulation by the US? Currency manipulation is commonly understood to occur when a government actively weakens its exchange rate to make its goods cheaper to foreigners and to prop up exports.

But when the peso depreciates, precisely the opposite happens: the dollar becomes stronger against the peso, not weaker. This fact alone would debunk any claim that the US recently manipulated the peso-dollar exchange rate. (READ: Diokno contradicts Duterte: No manipulation of PH peso)

Conclusion: Let’s not read too much into it

While the peso’s depreciation to a 7-year low is no cause for concern, it remains to be seen whether it will persist due to sustained capital flight. The government need only ensure that the business climate improves in the coming months, and not worsens.

If anything, the kerfuffle caused by the peso’s slump gave us a rare peek into the President’s understanding of market forces and global economics – views that we have not had much chance to hear given the intense focus on the drug war.

Moving forward, it’s good that we’re monitoring the progress of the Philippine economy under the Duterte administration using indicators like the peso-dollar exchange rate.

But sometimes there’s danger in reading too much into it, and reacting disproportionately to otherwise regular daily or weekly movements in the exchange rate. More often than not, these are borne not by grand schemes of manipulation or conspiracy, but by plain old supply and demand. – Rappler.com

The author is a PhD student at the UP School of Economics. His views are independent of the views of his affiliations.