A recent Reuters article portrayed the Catholic Church as an institution intimidated by the new Philippine president and very careful in voicing its views on the bloody campaign of extrajudicial execution of drug users conducted by him. Retired Archbishop Oscar Cruz is quoted as saying that “the CBCP [Catholic Bishops Conference of the Philippine] has to be very careful because it might unnecessarily offend a good number of people with goodwill, who are Catholics themselves.”

Just when the Church’s moral leadership is needed most, it finds itself exercising self-censorship. The reason is that it is undergoing a very deep crisis of credibility, if not legitimacy – one that its leaders feel could worsen should it challenge President Rodrigo Duterte on the killings.

The road to crisis

The Catholic Church has long been losing its hold on the Philippines, as shown by the increasing prominence and strength of challengers like the Iglesia ni Cristo, the Kingdom of Jesus Christ of Pastor Quibuloy, and Protestant evangelical groups.

There was a great deal of hope for the Church’s renewal in the 1960’s with Pope John XXIII's launching of the Second Vatican Council. However, little headway was made against conservative theology and the continuing emphasis on rituals, leading to many socially conscious priests and nuns leaving the priesthood and sisterhood to become key figures in the Communist Party and National Democratic Front in the 1970's and 1980's. Many others remained priests and nuns but became vocal opponents of Marcos and defenders of human rights. On the other hand, many, if not most, of the bishops remained supporters of the regime or stayed silent in the face of its abuses.

The role of Cardinal Jaime Sin, Archbishop of Manila, in the ouster of Marcos in 1986, helped restore some of the Church’s prestige and credibility, but this was mainly among the middle class. Over the next three decades, however, much of the restored credibility was frittered away by the continued emphasis on conservative theology and ethics and the perceived corruption of many bishops owing to their closeness to secular power. The reign of President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo from 2001 to 2010 was marked by her showering a number of important bishops with gifts like sports utility vehicles (SUVs) in return for their loyalty. Despite her entanglement in corruption, Arroyo was especially favored by the bishops because she came out in opposition to family planning.

The RH debacle

The strategic mistake the bishops made was to stake their credibility and resources on hardline opposition to the Reproductive Health Bill.

The battle over the RH bill lasted from 1998, when it was filed, till December 2012, when it finally passed Congress. The 14-year battle exposed the Church to many as an archaic institution battling a much needed social measure to address poverty that was supported by the vast majority of the poor. The unreasonable stand against the use of condoms even for prophylactic purposes to prevent sexually transmitted diseases and the silly claim that most anti-contraceptive pills were abortifacient did not gain the Church support among the poor, even as it shook support for the Church among large sectors of the middle class and the more liberal sections of the elite. They also drew attention to the fact that it was also the Church's opposition that had given the Philippines the notorious reputation of being the last country on earth – along with the Vatican, of course – with no divorce law.

It was the women's movement that finally defeated the Church in the fight over the RH Bill, and it did this by reframing the debate from population control to human rights; that is, the right to reproductive health was presented as a fundamental human right of women. Against the advice of some of the more enlightened priests and lay people, partisans of the hierarchy did not give up after they lost in Congress but took the battle over what was now the RH Law to the Supreme Court, where they again lost. Still unfazed, supporters of the bishops tried to gut the implementing rules and regulations of the new law, giving the image that the Church was not only breaching the divide between Church and State but also subverting majority rule, the central tenet of democracy.

Fear of Duterte

Thus the Church’s intransigence on the RH issue had already gravely undermined its legitimacy before Duterte appeared on the scene as a serious presidential candidate. In the days leading up to the May 2016 elections, the bishops issued a pastoral letter urging citizens not to vote for Duterte, though they did not name him.

Duterte’s counterattack was ferocious. He denounced the Church hierarchy for “moral hypocrisy,” citing their accepting favors from Gloria Arroyo. He also vowed to expose the “secrets of the Church,” which many took as a threat to name bishops and priests who had mistresses. His revelation that he had been abused by a Jesuit priest as a grade school student at the Ateneo de Davao was also seen as a threat to expose priests who sexually abused children. Perhaps more than anything else, this threat has effectively silenced most of the bishops, most likely because they do not want things to end up as in the United States, where the spotlight on clerical sexual exploitation of women and children has irreparably damaged the Church's credibility.

“Challenging the President’s campaign could be fraught with danger,” clergymen told the Reuters reporter. Apparently, the Church knows that, hobbled by its current crisis of credibility and legitimacy, it would be the loser in a head-on confrontation with Duterte at this point.

Burden of bearing witness

The Catholic Church in the Philippines now finds itself in the same situation that the Christian churches in Germany and Italy found themselves during the time of Hitler and Mussolini, two overwhelmingly popular leaders whose reigns were marked by widespread repression and, in the case of Hitler, mass murder.

Though few, the martyrdom of courageous Lutheran resisters like Dietrich Bonhoeffer, Sophie Scholl, and Hans Scholl went some way towards redeeming their faith. Sophie Scholl’s last words before being beheaded were “It is such a splendid sunny day, and I have to go. But how many have to die on the battlefield in these days, how many young, promising lives. What does my death matter if by our acts thousands are warned and alerted?”

While there were a few Catholic bishops who denounced Hitler and Mussolini, the acts of the Scholls and Bonhoeffer were rarely matched on the Catholic side. Indeed, Pope Pius XII’s failure to denounce and willingness to compromise with the Nazis and the Fascists has gone down as a notorious example of the Church’s putting its worldly interests ahead of its duty to serve as a witness.

Paradoxically, serving as witnesses to injustice against repression at times when it is not popular to do so has served as the route of redemption and renewal for religious communities experiencing crises of legitimacy. As Tertullian, the early Christian thinker, so wisely observed, “"the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church."

It is a truth that the faithful of the Catholic Church and other religious communities must now be pondering as the number of deaths in Duterte’s bloody campaign moves inexorably towards 4000. – Rappler.com

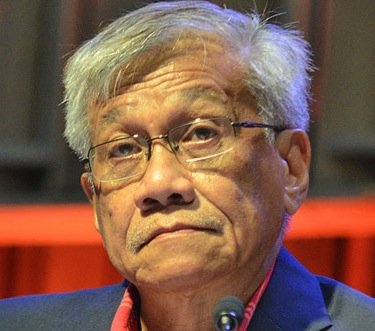

Walden Bello was one of the principal authors of the Reproductive Health Law when he served as a member of the House of Representatives. He is currently a visiting senior research at the Center for Southeast Asian Studies of Kyoto University and professor of sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton.