It must be very hard to be an American-Filipino – immigrant, but with dual citizenships, suburbanite, and a Rodrigo Duterte voter these days.

It must be very hard to be an American-Filipino – immigrant, but with dual citizenships, suburbanite, and a Rodrigo Duterte voter these days.

For one, Digong challenges their American souls. Having moved out from the home country to the United States, one has changed one’s formal fidelities. In many cases, the transformation is not even just legal (brown passport to blue passport), it even sinks deep into the persona.

The American-Filipino begins to talk like the characters in Bay Watch or Friends, trying as hard as he can to mimic the California twang but often with considerable difficulty – in moments where he relaxes his guard, the Visayan, Ilocano, or even Fairview accent jumps out.

(The favorite impish thing I usually do when encountering these Doña Victorina types is to relentlessly talk to them in Visayan, until a crack develops in their accents and this gives way later on to a full admission that they were indeed, Boholanos from Carcar. After the veil of Pamela Anderson’s accent is lifted, the conversation becomes more cordial and amusing.)

What does not change is one’s fidelity to the United States. The Pinoy migrant carries this across the Pacific and displays this with pride once the green card becomes a passport.

Readers might think this odd, but the statistics say otherwise. In 2014, the Pew Research Center ran a survey of which countries like and do not like the United States. And here it is worth quoting one segment of that research. The authors of the study wrote:

“Asians are also pro-American. In fact, the Filipinos are the biggest fans of the U.S.; 92% express a positive view. South Koreans (82%), Bangladeshis (76%) and Vietnamese (76%) also agree. Even half the Chinese give Uncle Sam a thumbs up. However, Pakistanis (14%) share no love for the United States…”).

What makes this figure fascinatingly odd is that Americans themselves do not have high regard for their government. The authors add:

“Barely half in the U.S. (51%) think their government respects individual freedoms today, down from 63% last year, 69% in 2013 and 75% in 2008, the first time the question was asked. This view is more common among Democrats (62%) than Republicans (50%) or independents (42%).”

Even before they left the home country, therefore, Filipinos were ready to become Americans. They were building a new life in a place where half of its citizens are not even happy with the state of things.

It stands to reason that how their new government – no matter how flawed – views the world is also theirs, and how it relates to other countries – including the Philippines – is also something they would support.

Second, many left the Philippines for a place of peace and security. And that place is the United States. American-Filipinos look back at the home country as a haven of all the bad things humanity has done to itself.

Do you want to talk about crime? Check the Philippines. How about smuggling? Check out the southern Philippines. How about corruption in high places? Philippines pa rin (still). And what about wars and revolutions? Ahem…the Philippines has that too.

It goes without saying that American-Filipinos see the Philippines as dark and foreboding territory, to be avoided especially by their children considering going back to claim their part of the heirloom. This is a popular impression in this part of the world; it is also false. A quick check of the crime indices of the two countries shows that the United States’ is higher (48.68) than that of the Philippines (38.99).

The popularity of the Philippines-as-a-dark country, however, always trumps the historical error, and an offshoot of this is this tendency by many American-Filipinos to think that, since they live in a more peaceful place, they have the right to be self-righteous in their opinions about the home country.

American-Filipino newspapers, therefore, write about Philippine events in the same way our tabloids report the news: the more gory, the more corrupt, the more inefficient, the dirtier – all the better. Their columnists write about the country as if they are part of the national conversation, and that Filipinos actually listen to their recriminations.

The most bizarre commentary, however, is this American immigration attorney's warning of “demonic forces” now possessing Catholic Philippines and, calling for the “salvation” of Duterte’s blighted soul, forgetting that this could not be done through Divine intervention, but through the ballot box. God has no time for Americans whining about countries they are not part of anymore.

A Filipina friend’s response to the nagging was apt: “Should this fellow be more worried about the possibility that his next president will be a sexual predator and a nut?”

These “concerns” however reflect a deeper fear that, by and large, Filipinos may care less already about what ex-Filipinos or American-born Filipinas think about them, this a product not so much of the anti-American diatribes of Duterte, and more a new-found confidence of the ability of Filipinos to stand and go at it on their own.

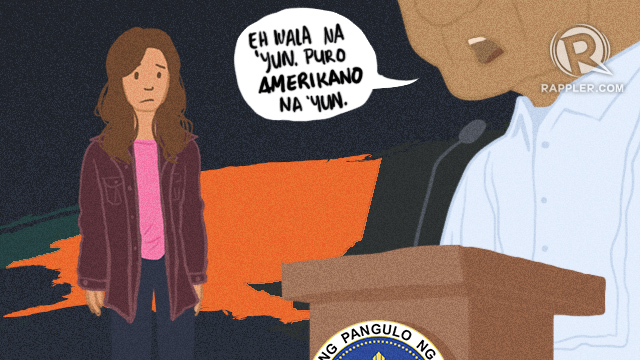

And herein lies one source of the intense discomfort when, in response to a question whether he worried about how American-Filipinos think of him, Digong snidely answered, “Eh, sabihin niya (Obama), well there are many Filipinos there (living in the US). Eh, wala na ‘yun. Puro Amerikano na ‘yun.”

It is this fear of the American-Filipino’s growing irrelevance in the conversations in the home country. (To be continued)– Rappler.com

Patricio N. Abinales is an OFW.