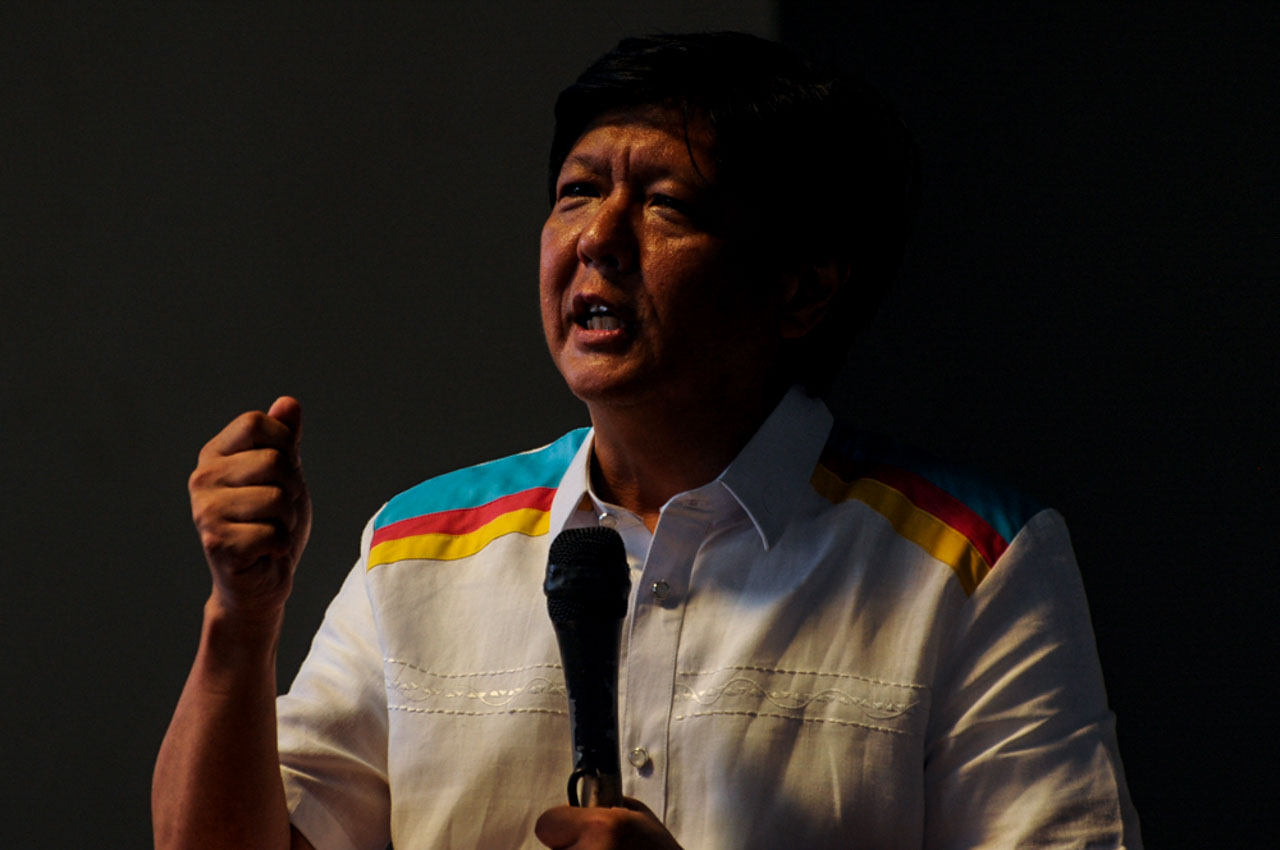

It's been some time since President Duterte uttered the name of Ferdinand ("Bongbong") Marcos Jr, and, given the frequency with which he did so before, and the reason why – to reaffirm that Bongbong was his anointed – some people feel somewhat relieved.

While they don’t see the neglect as any indication of a weakened standing of Bongbong with Duterte, they are thankful to not be reminded, at least for the moment, of the prospect of a second-generation Marcos presidency.

To be sure, the Duterte-Marcos partnership is too strong and too deep-rooted to be shaken. For one thing, Duterte, by his own proud admission, received financial support from the Marcoses for his electoral campaign; for another thing, not only is he a professed idolater of Ferdinand Marcos Sr, he has threatened to rule by martial law, as Marcos himself ruled, for 14 years – the idolatry is so pure he had even proposed that Marcos be buried a hero – and he was. Now he sees Bongbong as both a worthy son to the father and a worthy heir to him.

So much, indeed, is stacked up in Bongbong's favor a dissenter could use some respite from being reminded about it. There is simply so much else going on that is difficult enough to take.

Bongbong came close to being elected vice president. Victory would have made him official successor to Duterte if he chose to abdicate, a scenario Duterte himself raised as a possibility. But the possibility is not automatically eliminated by Bongbong’s defeat; he is vigorously disputing Leni Robredo's win over him, and lately he has been showing a spoiled brat’s impatience with the Supreme Court.

“Public interest demands,” he told the Court, that it resolve his protest “with dispatch, to determine once and for all the genuine choice of the electorate . . . it is neither fair nor just to keep in office for an uncertain period one whose right to it is under suspicion.”

Understandably, Bongbong can’t wait. He is not used to waiting – or, for that matter, losing. During his father’s regime, he – as everyone else in the family and certain cronies – had got his wishes without delay, until a popular rising booted them out of power. But life in exile had been too short and too comfortable for any chastening to happen.

Perspective on justice

In 6 years Bongbong was back in the country with his widowed mother and two sisters, and in no time all of them were readmitted into proper society and returned to power. Mom Imelda is now in Congress, older sister Imee governor of their province, and younger sister Irene a high-society butterfly and patroness of the arts. Bongbong had been a senator himself before he ran for vice-president. None of them spent a day in jail for the murder and plunder of the Marcos dictatorship.

Now, how can Bongbong be expected to be patient? And, with his perspective on justice formed by observing his own father make the law and dictate on the courts, how can he be expected to be deferential toward the Supreme Court? Is this not the same Supreme Court that has allowed his father to be buried a hero, thereby effectively granting President Duterte’s open wish?

Bongbong’s conception of “public interest” or what is “fair” or “just” can only come from a sense of entitlement: He is Ferdinand Marcos Jr, son of Ferdinand Marcos Sr, and the anointed political heir to President Duterte. How can Leni Robredo and the Supreme Court deprive him of his deserved justice?

But who can tell Bongbong Marcos with any certainty or authority that in these times his wish no longer has the force of command? His wish, after all, tends to coincide with President Duterte’s own. – Rappler.com