![]()

The Nazi-like arrest of CEO Maria Ressa of Rappler by the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) on orders from Malacañang is shaping up as one of the biggest setbacks of the Duterte administration. The outpouring of anger both at home and abroad indicates that, as Ressa herself pointed out, the Palace “crossed the line,” and this may well be the start of a concerted citizens’ pushback against the President’s dictatorial ambitions.

One wonders, however, if things would have gone this far had people displayed the same outrage when Senator Leila de Lima was summarily hauled to prison on charges of complicity in the narcotics trade fabricated by the government nearly two years ago, on Feb 24, 2017.

De Lima’s clash with President Rodrigo Duterte began way before both were elected to national office in May 2016. As chairperson of the Commission on Human Rights (CHR) during the administration of Gloria Macapagal Arroyo, she displayed marked independence from the person who appointed her, using her office’s investigative powers to go after institutions and people long regarded as untouchables, like the military and powerful politicians. One of the people she investigated in 2009 was then-Davao mayor Duterte in connection with charges that he maintained a death squad that was said to have been responsible for the elimination of hundreds of people.

It was a bold move, and it evoked hostility or non-cooperation, both from Davao city officials as well as local citizens. Indeed, De Lima barely escaped assassination during a trip to a quarry where the remains of victims of the DDS were disposed, according to the testimony of a former gunman who said he had received his orders from Duterte himself.

Owing to such obstruction, the CHR was not able to complete its report on the “Davao Death Squad” (DDS), and soon de Lima was overwhelmed with her tasks as Secretary of Justice under the Aquino administration that took office in July 2010. But Duterte did not forget nor forgive. In an interview I did with her in 2017, De Lima recalled, “He got a tape about an interview in Davao where I said that I would prove that there is DDS and he’s behind it. When he became President, he said in a public event that he would make me eat the CD.”

Kicking the hornet’s nest

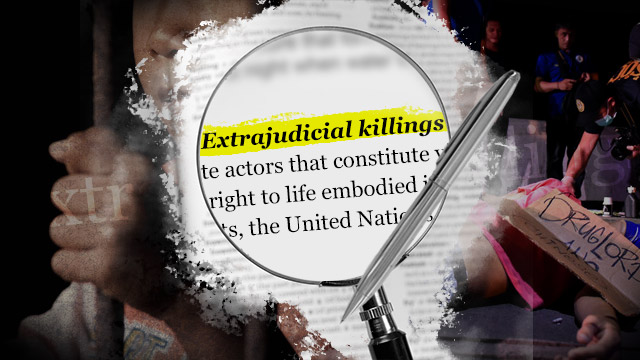

With Duterte elected president and De Lima senator in May 2016, it was inevitable that the President’s authoritarian manner and vengeful streak would sooner or later cross paths with de Lima’s dedication to human rights. That fated clash took place when, as the new chairperson of the Senate’s Committee on Justice and Human Rights and against a background of mounting deaths that accompanied the new administration’s war on drugs, De Lima convened hearings on extra-judicial killings (EJK’s), the initial focus of which was shedding light on the activities of the Davao Death Squad.

This was, as many saw it, kicking the hornet’s nest.

Indeed, Malacañang unleashed a massive offensive to discredit De Lima, commanding then Secretary of Justice Vitaliano Aguirre to concoct charges of her conspiring in the drug trade with convicted drug lords at the New Bilibid penitentiary where she had led raids while she was chief of the justice department.

In the Senate, Senator Richard Gordon, with his usual acute canine sense of the trail to power, took the cudgels for Duterte in undermining De Lima’s investigation into the DDS.

In the House of Representatives, sensing an opportunity to ingratiate himself with Duterte, the restlessly ambitious Representative Harry Roque sought to discredit De Lima’s character by turning a congressional probe into Malacañang’s drug conspiracy charges against her into a salacious fishing expedition for details of her personal relationship with her former driver, a line of questioning that was condemned by his own party, Kabayan, as encouraging a “prurient atmosphere.”

It was a performance in dirty dancing that led to Roque’s eventually being named spokesman of the person he had, prior to the 2016 elections, denounced as a “self-professed murderer.”

With Duterte at the peak of his popularity, even De Lima’s own party mates’ defense of her was tepid and guarded, probably out of fear of Duterte’s wrath or intimidated by his misogynistic characterization of the senator as an “immoral woman.” She recalled, “No one really came to my rescue.“

But while political personalities evinced caution, there were many ordinary citizens who were angered by this turn of events and took to social media to air their protest. I penned the following Facebook post: “Napikon si Digong. Hindi kasi niya kayang takutin si Senator Leila, kaya personal attack na lang ang tira niya. Susunod na diyan ang paboritong pangungusap niya, de Lima, papatayin kita.’ Sabi nga nila, ‘outa sight, outa mind, outa control.’ Si Senator de Lima ay may katangian na wala sa isang katutak ng lalaking politiko na sumisipsip kay Digong: may lakas loob siyang tumindig sa isang maton.”

(Duterte was pissed. He couldn’t scare Senator Leila, so he resorted to an ad hominem attack. Next thing you know, he’ll bring up his favorite phrase, ‘De Lima, I’m gonna kill you.’ As they say, ‘outa sight, outa mind, outa control.’ Senator de Lima has a quality that all of those licking Duterte’s ass lack: the courage to stand up to a thug.)

It was a post that drove scores of trolls and hardline supporters of Duterte in the internet to a frothing, rabid response.

My post was not simply a gut response. As the head of the Committee on Overseas Workers’ Affairs of the House of Representatives from 2010 to 2015, I had the opportunity to work with then Secretary of Justice de Lima in my effort to bring to justice government officials who took sexual advantage of our female OFW’s and found her to be a person of solid principle.

Moreover, being a vocal critic of the double standards of then President Aquino, I also admired the way she resisted pressure to whitewash Aquino’s buddies accused of corruption, like then TESDA chief Joel Villanueva on the Napoles pork barrel scam. I simply found it hard to reconcile the upright official with whom I had the chance to work with the image of her as a high-level drugs enabler that Duterte’s people wanted the public to swallow.

‘Judicial strangulation’

My late wife’s struggle with cancer took me out of the country in search of a cure for much of 2016 and early 2017, so I was not able to minutely follow Duterte’s persecution of the senator.

But what I could sense from afar was that the country was entering a new phase in Duterte’s political takeover of the country. The EJK’s that began on Duterte’s assumption of office had hit poor families, who had little capacity to protest.

Duterte’s vocal political opponents, in contrast, came mainly from the middle class or the elite, and they had to be handled in a way that would not alienate the middle class and elite base that Duterte had mobilized around the drugs and crime issue. The strategy that evolved and was tested on De Lima might be called “judicial strangulation.”

Aguirre’s DOJ assaulted De Lima with 3 charges of conspiring with drug traffickers, and there were seven other nuisance initiatives filed in other bodies, including complaints before the Senate Ethics Committee, a motion filed by House of Representatives leaders charging her with allegedly discouraging her former driver and security aide from appearing at a congressional hearing, and a petition filed before the Supreme Court seeking her disbarment.

It was a full court press, but the main drug-related cases were so obviously a frame-up that four regional trial court judges inhibited themselves from hearing them, obviously for fear of irretrievably sullying their reputations by declaring her guilty.

Worried that giving De Lima her day in court in a trial would give her the opportunity to turn the tables on the administration, Malacañang settled on a strategy of indefinitely keeping her in detention, facing her with the choice of either fading away in the public consciousness or admitting guilt and submitting to the president.

De Lima knew that all it would take to secure her release was an act of contrition and a vow never to stand in the president’s way again. In an interview I did with her in August 2017, she brushed aside the option of submission, “By pleading to an offense – any offense – that I did not commit in exchange for some promise, I would be selling my mandate, not serving it. It would be tantamount to admitting that I am being charged, detained and oppressed for reasons other than the simple and incontrovertible fact that I dared stand up to the President in order to defend the human rights of our people.”

Fighting back

The prospect of fading Count of Monte Cristo-like from the memory of a fickle public was, however, real, so De Lima and her Senate staff set out to make sure her voice would continue to be heard. She sent out a tri-weekly “Dispatches from Crame” to show she continued to function as a senator behind bars, sponsoring legislation and communicating her views on a variety national issues to the people.

Her jailers, however, made sure to make her ability to function as a public official from prison as difficult as possible. She was deprived of the use of a cellphone, computer, and access to the internet as well as air-conditioning. Her requests for personal and legislative furloughs were all denied. No foreign visitors, including parliamentarians, were allowed to see her.

However, local news outlets like Rappler and international media and human rights organizations like the Asean Parliamentarians for Human Rights (APHR), kept her in the public eye. She garnered awards and accolades such as the Liberal International’s 2018 Prize for Freedom, Time magazine’s recognizing her one of the “100 Most Influential People of 1917, and Fortune magazine’s naming her as one of the “50 Greatest Leaders.” Coming mainly from western organizations, however, these honors might have backfired, with Duterte adopting the posture of wounded nationalism.

From De Lima to Sereno to Rappler

It is clear now that De Lima served as the test case for the use of legal strangulation to deal with the president’s enemies.

The next prominent victim was Supreme Court Chief Justice Maria Lourdes Sereno. Concerned that impeachment followed by a trial in the Senate would make Sereno a martyr, Malacañang came up with a legal maneuver that sent shock waves through the judicial establishment: that the Chief Justice’s appointment by President Aquino 6 years earlier was void ab initio (from the beginning) owing to her not having filed the required SALN (Statement of Assets and Liabilities) while she was still a professor at the University of the Philippines.

It was an outrageous move that would not have prospered had it not been devilishly dipped into the simmering anti-Sereno feelings among many of her fellow justices, whose toes the public relations-deaf chief justice had stepped on. But it showed the lengths to which Malacañang was going to abuse the law to get its way.

Overconfident from its humiliation of Sereno, the administration decided to move decisively against Rappler, which had been in its crosshairs since the early days of the administration for its fearless coverage of the war on drugs and Duterte’s drive towards total power.

But a three-pronged assault on the internet news provider deploying charges of violating the foreign ownership of media provision of the Constitution, tax evasion, and cyber libel was set back when NBI agents badly mishandled the serving of an arrest warrant for cyberlibel on Rappler CEO Maria Ressa, preventing her from immediately posting bail and forcing her to spend the night at the NBI offices.

Covered by television, the event ignited a massive local and international firestorm, with personalities like former US Secretary of State Madeline Albright and CNN talk show host Christiane Amanpour registering their protest at the attack on the freedom of the press.

Despite the Palace’s claim that it had nothing to do with the raid on Rappler, Duterte is smarting from the fiasco. Though the reaction to the raid may represent a new level of resistance to Malacañang, Duterte is not likely to let it get in the way of his determination to jail Ressa and close down Rappler and, more broadly, of his push toward dictatorship.

Long and hard fight ahead

Meanwhile in her cell at Camp Crame, De Lima is heartened by the outpouring of rage provoked by the Rappler raid. But she’s also realistic. She knows stopping Duterte is going to be a very tough fight owing to the president’s popularity. She once observed that the people in Davao did not cooperate in her investigation of the Davao Death Squad owing to their being “under the spell of Duterte.”

With Duterte as President, she thinks something similar has happened to the country. In a written response to a question I sent her, she ventured into political psychology, the favorite discipline of those who have attempted to understand the hold on the masses of previous fascist personalities like Hitler and Mussolini:

I think there are people who believe because they want to believe. They want to believe because they don’t want to face the reality of who they elected as President. That is the misconception we have about democracy. People feel invested in the person they supported, and they do not want to believe that he is capable of destroying an innocent human being for personal vengeance and political power, because if they admit that, they believe that they also have to admit that they made the wrong choice.

I think people aren’t yet prepared for that dose of reality…People must know that they are being lied to, but they are probably too weary to sort it out anymore. They have become so tired of, and, thus, desensitized to, separating the lies from the truth. There is truth in the saying that the truth hurts. People are perhaps not yet prepared to face certain truths.

She is, however, cautiously confident that “the time will come when they will be forced to acknowledge the truth,” though “it might take more lives to be sacrificed before that happens. Hopefully, when they are ready to be awakened, it would not be too late for all of us.” – Rappler.com

Walden Bello was chairperson of the Committee on Overseas Workers’ Affairs of the House of Representatives from 2010 to 2015.

![]()

(Inspirational speech na binigkas kamakailan sa Junior Executive Development course graduation ng isang malaking kompanya ng bangko sa bansa)

(Inspirational speech na binigkas kamakailan sa Junior Executive Development course graduation ng isang malaking kompanya ng bangko sa bansa)

The terrain of election campaigning has radically evolved in the past decade. From the traditional rallies and house-to-house visits, candidates' preferred strategy shifted to radio and TV advertisements in the late 1990s to 2000s. In the last two elections, we witnessed how campaigning significantly expanded to the internet. In the 2016 presidential elections, for example, we saw how the internet changed the face of political campaigning, eventually

The terrain of election campaigning has radically evolved in the past decade. From the traditional rallies and house-to-house visits, candidates' preferred strategy shifted to radio and TV advertisements in the late 1990s to 2000s. In the last two elections, we witnessed how campaigning significantly expanded to the internet. In the 2016 presidential elections, for example, we saw how the internet changed the face of political campaigning, eventually

What a wonder to behold – the global outburst of protectiveness for Maria Ressa on the eve of Valentine's Day.

What a wonder to behold – the global outburst of protectiveness for Maria Ressa on the eve of Valentine's Day.