After celebrating the 4th anniversary of the presidential inauguration, Duterte should be thankful to the 16 million Filipinos who voted for him. He should also thank the priests and religious who campaigned for him and voted for him even after cursing the Pope and after the CBCP’s appeal to the faithful to vote according to their conscience.

No survey has been conducted about how many percent of priests and religious supported him. What I have is anecdotal, personal knowledge and observation. In the religious community where I was living, most supported his candidacy, and I felt like a lonely voice warning them about the dire consequences (some of them even organized two victory celebrations in the church compound after the elections).

One confrere proudly told me to my face that he was voting for Duterte, knowing my stance. A seminarian wore a Du30 bracelet. There were 3 confreres who posted their photos on Facebook doing a fist bump. A contemplative nun campaigned on Facebook for him and even made her pet dog wear a Du30 collar. A diocesan priest who used to join me for my previous bike advocacy posted a Du30 baller on Facebook. Another diocesan priest who was my former student posted a selfie on Facebook wearing a Du30 cap. There were also diocesan priests from Mindanao who are now in the US who posted their photos on Facebook with the Du30 fist bump.

A priest texted me that most of the priests in his archdiocese in Mindanao were voting for Duterte as president and Bongbong Marcos for vice-president. Even progressive priests and nuns active in human rights and environmental advocacy supported him. A diocesan priest who was my classmate in the seminary told me his support for Duterte was the fruit of his spiritual discernment. While conducting a clergy retreat in the Visayas I got a negative reaction when I talked about the prophetic ministry and the need to denounce extrajudicial killings and the national leaders behind it. (READ: [OPINION] What would Jesus do: The Christian dilemma in the time of Duterte)

Thus, it cannot be denied that there were many priests and religious who supported Duterte and can be regarded as DDS (Diehard Duterte Supporters). The question is, why did they support Duterte and help enable him to power?

There are many underlying motivations. The first is regionalism. Many priests from Mindanao – especially the Davao provinces – instinctively supported him (“ato ni bay” – he is ours). When the Diocesan Clergy of Mindanao held their annual gathering in Davao a year before the elections, Duterte was invited as a guest speaker. It didn’t surprise me to learn later on that many diocesan priests supported him. Regionalism is part of the Philippine political culture and priests who lack critical faculty can be influenced by this. My classmate who told me that he voted for Duterte after a process of discernment was most likely influenced by regionalism rather than the Holy Spirit. My Redemptorist confrere who told me to my face that he was voting for Duterte also came from Davao.

Another factor is ideological. Many progressive priests and religious supported Duterte’s candidacy. He had a reputation for being a friend and ally of the Left even as mayor of Davao. During the campaign period he announced that he would be the first Leftist president. He promised to establish a coalition government with the Left and even a revolutionary government. A progressive association of religious sisters once invited him to be their guest speaker during an annual assembly in Davao. The progressive clergy and religious believed that Duterte could finally come up with a peace agreement with the NDF and that he could fulfil their dream of changing Philippine society radically. This is the same reason why the revolutionary Left led by the CPP and NDF supported Duterte. They were filled with euphoria when Duterte appointed 4 Leftists to the cabinet, released political prisoners, and resumed the peace process. Regret would come later.

There are other underlying reasons why priests and religious supported Duterte. A university president who is a religious priest believed in Duterte’s political will to bring about change and progress in the country, especially in Mindanao. When reminded about the extrajudicial killings, he used the argument of the common good as part of the equation. Many other priests and religious have used this reason. They believed that only a strongman like Duterte could save and change Philippine society – pagbabago. (READ: Why Filipinos believe Duterte was 'appointed by God')

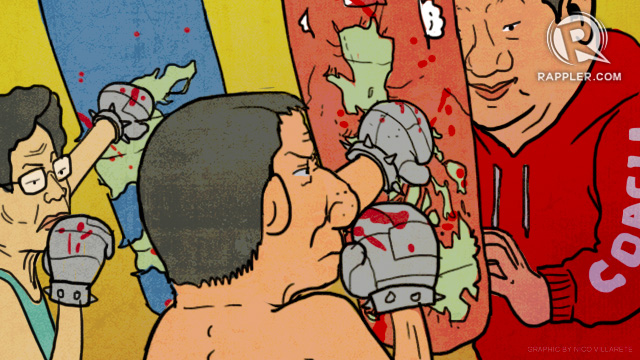

Whatever their motivation, the support of many priests and religious for Duterte may have helped create the bandwagon effect. By expressing their support through social media (selfies with fist bumps, ballers, caps, etc.) they were able to influence others (especially pious lay people) to throw their support behind Duterte’s candidacy. They were like shepherds leading their flock to follow the big bad wolf. This could explain why many either defended him or remained silent as the president’s incompetence and brutality became more apparent, even when he continued to attack the Church. (READ: [OPINION] God gave us Duterte)

A time of accounting will come – like what happened after the Hitler/Nazi era. We will never forget those who helped bring into power a brutal incompetent autocrat with messianic pretensions and kept him in power. Priests and religious will not be exempted from this reckoning. This is part of a shameful episode in the history of this country and of the Church, which cannot be glossed over or covered up.

It is not too late to make amends. What is important is to admit and learn from their mistakes. There are some who have already redeemed themselves after realizing their error. They rediscovered their prophetic voice – they spoke out against extrajudicial killings, denounced human rights violations, helped provide sanctuary to witnesses, provided aid for the victims of the incompetence of leaders in time of the pandemic, etc. I hope that in the remaining two years there will be more priests and religious who will act as courageous prophets and good shepherds, who will protect their flock from the wolves.

A time will come when those who dedicated their life to God and His people will have to answer: whose side were you on? There is no room for neutrality in the struggle between good and evil. – Rappler.com

Father Amado Picardal is the executive co-secretary of the Commission for Justice, Peace, and Integrity of Creation of the Union of Superiors General in Rome.

May kinagalitan ako noong isang araw. Dati kong estudyante sa isang state university. Nakita kong nakikipagtalo sa online comments section ng isang pahayagan. Mahaba ang thread at, obviously, walang intensiyon na malinawan ang katalo, na minumura na at iniinsulto ang dati kong estudyanteng hindi maiwasang hindi mapikon. Gumaganti sa diskursong marumi pa sa burak ng kanal sa isang baradong estero sa Kalakhang Maynila ngayong tag-ulan.

May kinagalitan ako noong isang araw. Dati kong estudyante sa isang state university. Nakita kong nakikipagtalo sa online comments section ng isang pahayagan. Mahaba ang thread at, obviously, walang intensiyon na malinawan ang katalo, na minumura na at iniinsulto ang dati kong estudyanteng hindi maiwasang hindi mapikon. Gumaganti sa diskursong marumi pa sa burak ng kanal sa isang baradong estero sa Kalakhang Maynila ngayong tag-ulan.