I stand as a character witness to the public life of Senator Leila de Lima. Although I am not close to Senator De Lima personally, I have observed her conduct for many years now – first as an election lawyer, and later as a public official. I am not privy to her private life and her love life is not my concern.

I stand as a character witness to the public life of Senator Leila de Lima. Although I am not close to Senator De Lima personally, I have observed her conduct for many years now – first as an election lawyer, and later as a public official. I am not privy to her private life and her love life is not my concern.

I must also say that I have not always supported Secretary De Lima’s official acts, including the Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (GMA) case, the problems at the New Bilibid Prison, and the ongoing Senate hearings. But none of my criticisms is enough to overturn my judgment of Senator de Lima as a good public servant. She is, following Saint Thomas More, patron saint of lawyers and public officials, a woman for all seasons.

At the outset, I must also say that I support many of President Duterte’s initiatives, particularly the peace process, constitutional change, the economic reforms being proposed, and the war against illegal drugs if pursued without human rights excesses.

I also support a strong leader with formidable political will as that is required by many of our challenges. But it is precisely because of that support, that I believe a strong opposition is important. As a governance person, I believe that it is in the conflcit of ideas, that the best solutions are found. The worst thing that has happened in our politics today is the lack of a strong opposition. Right now, Senator De Lima is one of the few politicans who has stood up to play this role. We need her to continue doing that.

De Lima as election lawyer

A San Beda College of Law graduate and bar topnotcher (ranking 8th in the 1985 exams), Senator De Lima is known for her professionalism and courage, more than anything else. As one of the leading election lawyers in the Philippines, her clients included the likes of Senators Manny Villar, Alan Peter Cayetano, and Koko Pimentel.

She stood as the lawyer of Cayetano when a nuisance candidate with the same name as the senator, a dockworker from Davao, was fielded to undermine his candidacy as a result of his perceived opposition to then President Arroyo, as well as his exposés on the alleged corruption of former first gentleman Mike Arroyo. It was then said at the Comelec that the order to dismiss the case and allow the nuisance candidate to run came from the very top. De Lima nevertheless went on to win the case for Cayetano, and the senator got his Senate seat.

As early as her election law practice, De Lima was already recognized for her determination, at the risk of her own personal safety. She hazarded appearance at the very heart of the Ampatuan kingdom in Maguindanao, protesting manufactured election returns to contest the impending proclamation of the warlord family’s candidates, only to be told by fellow election lawyer and future Comelec Chairman Sixto Brillantes Jr that she has done enough, and that it was better if she left the canvassing center with him before it got dark.

Several years later, De Lima went back to Maguindanao, this time as Chairperson of the CHR (Commission on Human Rights) to see first-hand the tableau of 58 dead bodies found on a hilltop in Ampatuan, Maguindanao. It was the same danger she faced when she challenged the rule of the Ampatuans years earlier as their opponent’s election lawyer.

Heading the Commission on Human Rights

When she was appointed by President Arroyo to head the Commission on Human Rights, there was speculation that the decision was moved by the desire to deprive the opposition of its most effective election lawyer.

Whatever the reason, subsequent events showed that De Lima only ceased to be a thorn insofar as lawyering for the opposition was concerned. She proved to be a thorn in the Arroyo administration in another manner, when she proceeded to conduct serious investigations on human rights violations committed by the military which was then conducting extra-legal operations against known leftist militants.

One of these included the case of the two UP students who were abducted and went missing, which eventually led to the arrest and prosecution of General Jovito Palparan. It was also during De Lima’s stint at the CHR that the abduction case of Jonas Burgos was investigated by the CHR, as well as other cases of abduction including that of an alleged Abu Sayyaf member who was the victim of mistaken identity by the military.

These stories showed that De Lima as CHR Chairperson was not inclined to be partial towards the background of human rights victims. As long as there was a human rights violation committed either by the State or a non-state actor, regardless of what the military made the victim to appear to be, she was bound to investigate and call the perpetrator to task.

It was this characteristic empathy for victims of human rights violations that led her to investigate a particular case that nobody dared touch until then, for the reason that the victims were the lumpen dregs of society, the alleged petty criminals, pushers and addicts of the slums of Davao City.

One thing that resulted from the CHR hearings on the DDS was the fact that the killings on the streets of Davao eventually decreased, if they did not totally stop altogether. The national spotlight focused on the Davao killings because the CHR investigation forced the DDS to lie low at some point, especially after the discovery of human remains inside the compound of a firing range owned by a former Davao policeman, which was also known as the DDS training ground.

De Lima’s tenure as justice secretary

As Secretary of Justice, De Lima continued to collect the enemies that would one day seek her “karma,” in the words of former first gentleman Mike Arroyo and, more recently, the daughter of Senator Juan Ponce Enrile.

Preventing GMA from going abroad, and eventually causing her arrest and detention through the entire term of President Aquino, was just the start of her colorful career in collecting enemies as secretary of justice. I have written that, in retrospect, it would have been better if GMA was granted bail, given the evidence against her which saw the Supreme Court acquitting the former president.

De Lima did not stop with the Arroyos.

In the aftermath of an NBI rescue operation of a kidnapping victim, Benhur Luy spilled the beans on a scandal that was to rock the entire country. The PDAF [Priority Development Assistance Fund] scam was investigated by the National Bureau of Investigation (NBI) under De Lima’s direct control and supervision, and resulted in the filing of cases, arrest and detention of congressmen and Senators Juan Ponce Enrile, Jinggoy Estrada, and Bong Revilla for plunder.

This earned her the ire of certain quarters for implementing selective justice, as only the opposition politicians were being singled out. This was inaccurate. The PDAF scam complaint sheets submitted by the NBI to the Ombudsman included administration officials and close Aquino friends and allies such as former Customs Commissioner Ruffy Biazon and now Senator Joel Villanueva.

Her list of enemies did not only include these powerful national figures. Ironically, she is now being linked by President Duterte to the same Bilibid drug lords whose hegemony in the national penitentiary De Lima broke apart when she personally led the raid on their “kubols” in December of 2014. In the aftermath of the raid, the drug lords filed administrative and criminal cases against De Lima, using top-caliber lawyers paid with drug money.

No fortune to show

One or two sent her death threats. That these same drug lords would give her protection money or finance her election campaign, after De Lima has destroyed their Bilibid drug network and isolated them in a separate detention building, does not add up.

For one, she has no fortune to show, at least none that we know of, that is commensurate to the imagined protection money that drug lords would give a Cabinet secretary.

With supposed millions in drug payoffs, why build a house in the middle of rice fields in Urbiztondo, Pangasinan, when you can very well buy a spot in Ayala Alabang?

De Lima does not even own the house she lives in, here in Manila. She is renting it.

President Duterte might have the so-called “intercepts” of communications between the Bilibid drug lords and De Lima’s driver, or he may even produce evidence against one or two DOJ officials linked to her.

But the most important question that the President should answer is, “Where is the money?”

Without evidence of the drug money in De Lima’s accounts, or without evidence of properties accumulated in her name that is not justified by her income as a public official or as a former election law practitioner, the accusations that De Lima received drug money from drug lords amounts to nothing but the persecution of the senator.

This is not to say that Senator De Lima is completely unaccountable for the state of the Bilibid prison during her tenure as secretary of justice. She could have been more aggressive, for example. If there were limitations, legal and political, that constrained her, it would be good to have that out in public.

The Senate hearings

The first two hearings of the Senate Committee on Justice and Human Rights show that, in spite of the personal attacks on her, De Lima is still capable of being objective in the inquiry on the extrajudicial killings, at least as much as a person who is obviously affected by accusations of graft and corruption can be against the government that is accusing her.

There were instances, however, when she could not avoid being defensive about her record as justice secretary who exercised supervision over the New Bilibid Prison, when charges of negligence and complicity in the proliferation of drugs at the Bilibid surfaced during the hearings. In my view, when she took on this defensive mode, the hearings became distracted.

No matter how affected the senator is, she must stand true to herself and her own record as a professional lawyer and public servant. The hearing is not about the accusations against her, but about the administration’s strategy in its war on drugs, and how this is coinciding with the unusual and alarming rise in the killing of drug suspects during police operations and the extrajudicial killing perpetrated by vigilantes.

I am hoping that President Duterte and his supporters will realize that a De Lima is needed as the administration moves forward in its agenda on illegal drugs, As I have written elsewhere, the possibility of an international criminal case against the President and his public safety officials cannot be ruled out. I am personally against such a case but the building blocks for it can now be assembled. The Senate hearings, if they result in a more rights-oriented approach to the illegal drugs problem, will help blunt such a case.

The lawyer’s oath

Five hundred years ago, in England, a lawyer and top government official had to stand up to his King. His name was Saint Thomas More, now recognized as patron saint of lawyers and government officials. More was not a perfect man; both his personal and public life were stained with personal flaws, including pride and being too harsh and judgmental on others.

But at the most important point of his life, More stood steadfast to his principles and conscience. That is why, Robert Bolt honors the saint with his play A Man for All Seasons. In one of the most memorable scenes from the movie adaptation of Bolt’s play, More tells his daughter: “When a man takes an oath, he's holding his own self in his own hands like water, and if he opens his fingers then, he needn't hope to find himself again.”

Senator De Lima is also a woman for all seasons. She is an imperfect woman, morally flawed for sure as many of us (author included) are. But like Saint Thomas More, she is only doing her duty.

It is a duty to uphold the Constitution, as the lawyer’s oath provides: “I, do solemnly swear that I will maintain allegiance to the Republic of the Philippines, I will support the Constitution and obey the laws as well as the legal orders of the duly constituted authorities therein; I will do no falsehood, nor consent to the doing of any in court; I will not wittingly or willingly promote or sue any groundless, false or unlawful suit, or give aid nor consent to the same; I will delay no man for money or malice, and will conduct myself as a lawyer according to the best of my knowledge and discretion, with all good fidelity as well to the courts as to my clients; and I impose upon myself these voluntary obligations without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion. So help me God.” – Rappler.com

The author is former dean of the Ateneo School of Government

“The Philippines is deeply divided. One only needs to read the comments on online news articles and social media posts to realize this.”

“The Philippines is deeply divided. One only needs to read the comments on online news articles and social media posts to realize this.”

I think everyone will agree that the social media environment has become toxic as far as political discourse is concerned.

I think everyone will agree that the social media environment has become toxic as far as political discourse is concerned.

Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas issued a pastoral message on the

Lingayen-Dagupan Archbishop Socrates Villegas issued a pastoral message on the

Below are excepts from the

Below are excepts from the

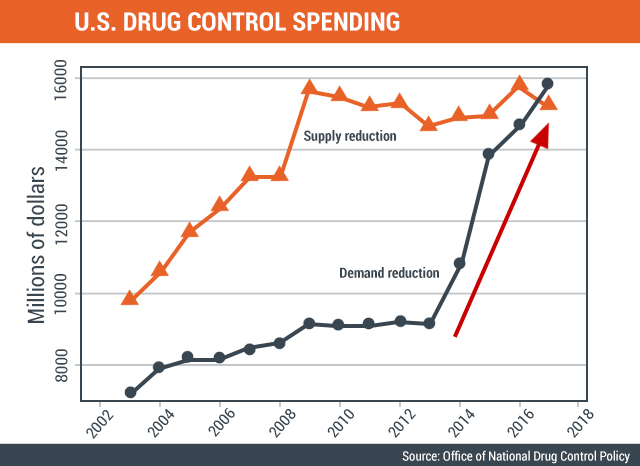

For the next couple of years, drug and crime reduction will likely remain at the forefront of the national development agenda.

For the next couple of years, drug and crime reduction will likely remain at the forefront of the national development agenda.

For this year's World First Aid day, the focus is all about children.

For this year's World First Aid day, the focus is all about children.

I have often been asked on nationwide television as well as in radio interviews to explain one legal concept or the other – the latest, on the writ of habeas corpus. I was told by my friend that one netizen had bashed me for proferring my opinions despite the fact that I am not a lawyer. He even went so far as to question my eligibility to be dean of a graduate school of law without being a member of the Bar. In the first place, I do not offer my opinions. I am asked for them, and an educator at heart never passes up an opportunity to educate. This is not the first time a challenge like this is hurled my way, but I am no longer flustered. What it does make clear, though, is that we have cultivated this deleterious mentality that treats disciplines like enclaves of professionals, jealous about the profit realized from the exercise of their professions.

I have often been asked on nationwide television as well as in radio interviews to explain one legal concept or the other – the latest, on the writ of habeas corpus. I was told by my friend that one netizen had bashed me for proferring my opinions despite the fact that I am not a lawyer. He even went so far as to question my eligibility to be dean of a graduate school of law without being a member of the Bar. In the first place, I do not offer my opinions. I am asked for them, and an educator at heart never passes up an opportunity to educate. This is not the first time a challenge like this is hurled my way, but I am no longer flustered. What it does make clear, though, is that we have cultivated this deleterious mentality that treats disciplines like enclaves of professionals, jealous about the profit realized from the exercise of their professions.