![]() No field manual or doctrine is expected to survive the quick changes in this uncertain and complicated operational environment. After all, violent conflicts in every maturing democracy are the mark of this modern world.

No field manual or doctrine is expected to survive the quick changes in this uncertain and complicated operational environment. After all, violent conflicts in every maturing democracy are the mark of this modern world.

In my case, it will be a lot easier to tell you about the errors we made before we got it right, and how bitterly the Armed Forces of the Philippines (AFP) learned from those errors.

We have all types of long-running insurgencies. Name it, we have it – communist insurgency, Muslim rebellion, terrorism.

These conflicts have taken a huge toll on our economy and on the character of the AFP.

I have seen enough death and sufferings from both ends. When I was a young soldier, we were there to follow the lead of our predecessors. Not one of our superiors bothered to tell us what good that would bring. We were expected to do terrible things, so horrible I cannot tell you specifically the circumstances.

We were made to believe, for example, that “a good Moro is a dead Moro.” Our seniors even had a way of saying that anyone twelve years and older is considered a combatant, and that the women will bear children who will eventually become rebels.

What we did in those years are precisely the reasons why the conflict continues to rage till today.

My story is not unique: all conflicts are contaminated with atrocities perpetrated by soldiers themselves.

I believe that using your own armed forces without the right frame of mind and direction, and against your own people, is a terrible and criminal mistake.

This is the reason why developed countries have constitutional provisions restraining the participation of their armed forces in local conflict. Australia has Section 51 of their Defence Act. Canada specifies the limitations within its National Defence Act. Britain has the same. US has the Posse Comitatus Law.

Other countries have similar legislations, if only to protect their citizens from misapplied or misused military capability.

What then is the role of the armed forces in a maturing democracy?

Understand that democracy is in some ways problematic. In developing countries, democratic space is open to misuse and abuse. This is also true for the militaries of developing nations.

In our case, the Philippines' sad experience on the misuse of military capability against our own people has generated lasting conflicts which will take generations to heal.

Changing mindsets

We have a disgusting experience of bad counterinsurgency policies. It was only in the last two decades that we recognized – and implemented – more coherent approaches.

The anti-subversion law was abolished and peace negotiation has been the direction.

The military has been in the midst of promoting security sector reform (SSR). We believe that SSR and counterinsurgency must come hand in hand and pursued aggressively.

We learned bitterly that our policies on counter-insurgency were mere knee-jerk reactions to the situation and did not include any exit strategy.

We learned to mimic what the rebels do at the countryside in order to win the hearts of the people.

We learned the necessity of putting in place senior officer supervision at every level of military activity.

We also learned that civil affairs and public affairs must not be seen as a tool to fight insurgency, but rather as a responsibility toward the less fortunate sector of society.

Our Armed Forces also learned that in order to preserve our gains and keep moving forward, we cannot fully rely on other agencies of government. We have to do it ourselves and hope that other agencies will toe the line lest they be criticized by civil society. We had to get away from the blame syndrome.

Note also that too much drumbeating about the efficiency of the military has driven some rightist sectors to advocate military takeover. That is definitely not the role of the military in a maturing democracy.

'Whole-of-society' approach

![]()

This whole-of-society approach is an offshoot of our 2010 National Security Policy.

The policy practically calls for the participation of the military in assisting poor communities. This calls for extreme interpersonal skills and a lot of adjustments.

We needed to learn very quickly the operations of every government agency. We had to adapt hastily in order to adjust our doctrine. We were, to some extent, doubtful of what we can accomplish within a timetable. But we did not want our plan to end up like its predecessors, which came short of its objectives at termination phases.

We focused on preserving our gains. We made sure that the last soldier understood the end state, the methodology, and his role.

It was prepared in collaboration with all sectors of society. It is an open document representing the consensus of all stakeholders.

Oplan Bayanihan, the operational plan for this policy, is anchored on our government’s peace framework. Efforts of the armed forces were focused on the more important goal of alleviating the roots and results of poverty. We envisioned it to be accomplished through genuine concern for the people and implemented in cooperation with all stakeholders. (Editor’s Note: Oplan Bayanihan has since been renamed to Development Support and Security Plan Kapayapaan or DSSP Kapayaan under the Duterte administration)

Beyond the battlefield

This is a paradigm shift.

It allows the armed forces to embrace the broader framework of human security. It gives emphasis on the non-kinetic dimensions of military operations to protect our people against poverty, malnutrition, illiteracy, and other peripheral threats.

The end state calls for capabilities of threat groups reduced to a level that they cannot threaten stability, and that civil authorities are capable of ensuring the safety and well-being of the people.

It has two strategic approaches. The whole-of-nation approach and the people-centered approach.

It is hinged on the participation of stakeholders and less of traditional military operations.

"Whole-of-nation" approach is about creating a shared understanding of security, not just among security forces, but also with the civil society and the communities. The role of the AFP is to unify all these efforts.

The people-centered approach works within the framework of human security. It puts the people’s welfare in the middle of every military activity. It gives primacy to human rights and the rule of law.

In essence, we underwent rapid paradigm shifts in order to show genuine concern for our people.

What war, what enemy?

Here are some of those paradigm shifts.

- First is that this is not a war; this is law-enforcement and community organizing.

- There is no enemy. Rebels or not, they are all citizens entitled to the same rights as any of us.

- Only when necessary, we shoot to maim and not to kill.

- Our Rules of Engagement: No shooting unless shot at.

- Zero collateral damage. No such thing as acceptable collateral damage to lives and properties.

- Human rights and rule of law are our constraints as well as restraints.

- “Do the right thing” and not confined to “Doing things right”.

- HAIL, which stands for Honesty, Authenticity, Integrity, and Love.

- Threat to use force is supreme over the actual use of force. Strategic significance of any military operation is not proportional to the size of troops involved.

- The best closure to any insurgency is through a peaceful settlement.

But many times politics comes in the way. Politicians use the issue for grandstanding. Then there goes the competition for resources.

Beyond AFP's control

We know that insurgency is a product of underdevelopment. Insurgency aggravates the inability of government to administer and alleviate an already miserable condition. And this leads to other problems on governance.

These problems make it difficult to reach a consensus toward a coherent national security policy.

Then we can add military adventurism where some not-very intelligent officers believe they can do better than the civilian bureaucrats in running the government.

The essence of a maturing democracy is among the principles we advocate among our soldiers and officers alike. This can be broken down into four:

First is a peaceful transition of power through election.

Without military presence, rogue politicians harass the voters or rig election results. Private armed groups proliferate, acting as goons for corrupt politicians.

For a time, the AFP itself was accused of involvement in rigging election results. We considered those days as the darkest hour for our armed forces.

What we are certain of, is that we have substantially reduced election violence and election fraud.

Second is a strong middle class. Unlike the more advanced societies, developing nations have a relatively small percentage of population that's considered middle class.

Why the middle class? These are the people who value justice, fairness, and predictability. These are the people who pay a huge portion of their income to taxes. They are the first affected by recession or price increases. They earn enough for food, shelter, clothing, and can afford to send their children to school. These are the people who keep the economy moving forward.

The contribution therefore of security and the military is to establish a secure environment good for the economy and for the rising middle class.

Of course we also need to take care of the poor. We want all of them to rise to the middle class level through education, health care, livelihood, and other opportunities. Democracy and decency, after all, are meaningless to an empty stomach.

Third is a functioning civil society. Civil society is usually represented by the middle class. These are the people who for love of justice and fairness allocate spare time to criticize the government and to be heard.

The problem however in maturing democracies, is that civil society is normally represented by leftist groups that criticize every government policy – leftists who hate the rich and the military.

Our job therefore is to ensure that no issues are thrown at the security forces and not to give any reason for civil society to discredit the military.

When we scrutinized the issues or so-called propaganda by the leftists, we discovered that all are valid despite some exaggerations. Their common issues against our military are: forced disappearances, militarization, and other human rights violations.

We knew that only after addressing these issues can we reestablish credibility. A policy was issued to engage these left-of-center groups. We invited them for discussions and forum. Our civil affairs people even had tours and team-building activities with them. The results were fascinating. We managed to dispel their misconception that the military serves as the tool of the oligarchs in oppressing the poor. We made them understand that majority of our soldiers also come from the same underprivileged class.

Fourth is economic development. Without economic development, it will be difficult to promote democracy. We believe that economic development or lack of it can awaken the people.

Challenges of a global insurgency

Today, we are faced with bigger challenges.

We must accept that we are faced with a global insurgency. Anti-globalization forces will act alone or in unison with other groups to disrupt our democratic ideals. Global insurgency shall persist for generations.

An insurgency without a center of gravity. An asymmetric conflict without a clear hierarchy of forces which we can address. A conflict which will not be over with one campaign plan. A conflict full of violence that will take many more innocent lives. A conflict which shall drive us to feel helpless in protecting the weak and the innocent.

In this kind of confrontation, our only effective weapon is our sincerity and empathy, both to the victims or would-be victims and to the insurgents as well.

Solutions will vary from village to village. We will find those solutions as we recognize their sufferings, as we feel what they feel. One victim of insurgency is one citizen we failed to protect.

You don’t go to Afghanistan or Iraq or elsewhere simply because you were told to. You go there to risk life and limb not for your career, not for your paycheck, and certainly not for bragging rights.

We risk our lives for other people whom we have never met, all in the name of democracy. We chose the gun as an instrument to make this world a better place. That gun is a symbol of both responsibility and authority.

We are prepared to shoot or kill in self-defense or in defense of our comrades, and of any innocent stranger.

For every terrorist or insurgent we kill, two more of his brothers will come as replacements. The fewer times we kill, the fewer adversaries we would have.

We shall fight any threat to democracy, with our hearts ahead of our guns. – Rappler.com

(These are excerpts from a speech delivered by retired army Lieutenant General Gaudencio Pangilinan Jr at the Australian Command and Staff College in Canberra in November 2015. The author served as counter-intelligence chief; commander of the AFP civil relations service; deputy chief of staff for operations; and commander of the AFP Northern Luzon Command, among others. We are publishing this with his permission and due to the timeliness of the points raised here.)

![]()

No field manual or doctrine is expected to survive the quick changes in this uncertain and complicated operational environment. After all, violent conflicts in every maturing democracy are the mark of this modern world.

No field manual or doctrine is expected to survive the quick changes in this uncertain and complicated operational environment. After all, violent conflicts in every maturing democracy are the mark of this modern world.

Here's the start to a nice story: you are fresh out of 5 years of medical school – two of which were spent holed up in a hospital with a host of seniors double-checking everything you do. A few months of board review, drowning in the kind of cross-correlated information overload that makes computers shut down and cry, you are off to a municipality of anywhere from 4,000 to 20,000 people after sitting through a whirlwind of PowerPoint presentations you have no way of relating to yet.

Here's the start to a nice story: you are fresh out of 5 years of medical school – two of which were spent holed up in a hospital with a host of seniors double-checking everything you do. A few months of board review, drowning in the kind of cross-correlated information overload that makes computers shut down and cry, you are off to a municipality of anywhere from 4,000 to 20,000 people after sitting through a whirlwind of PowerPoint presentations you have no way of relating to yet.

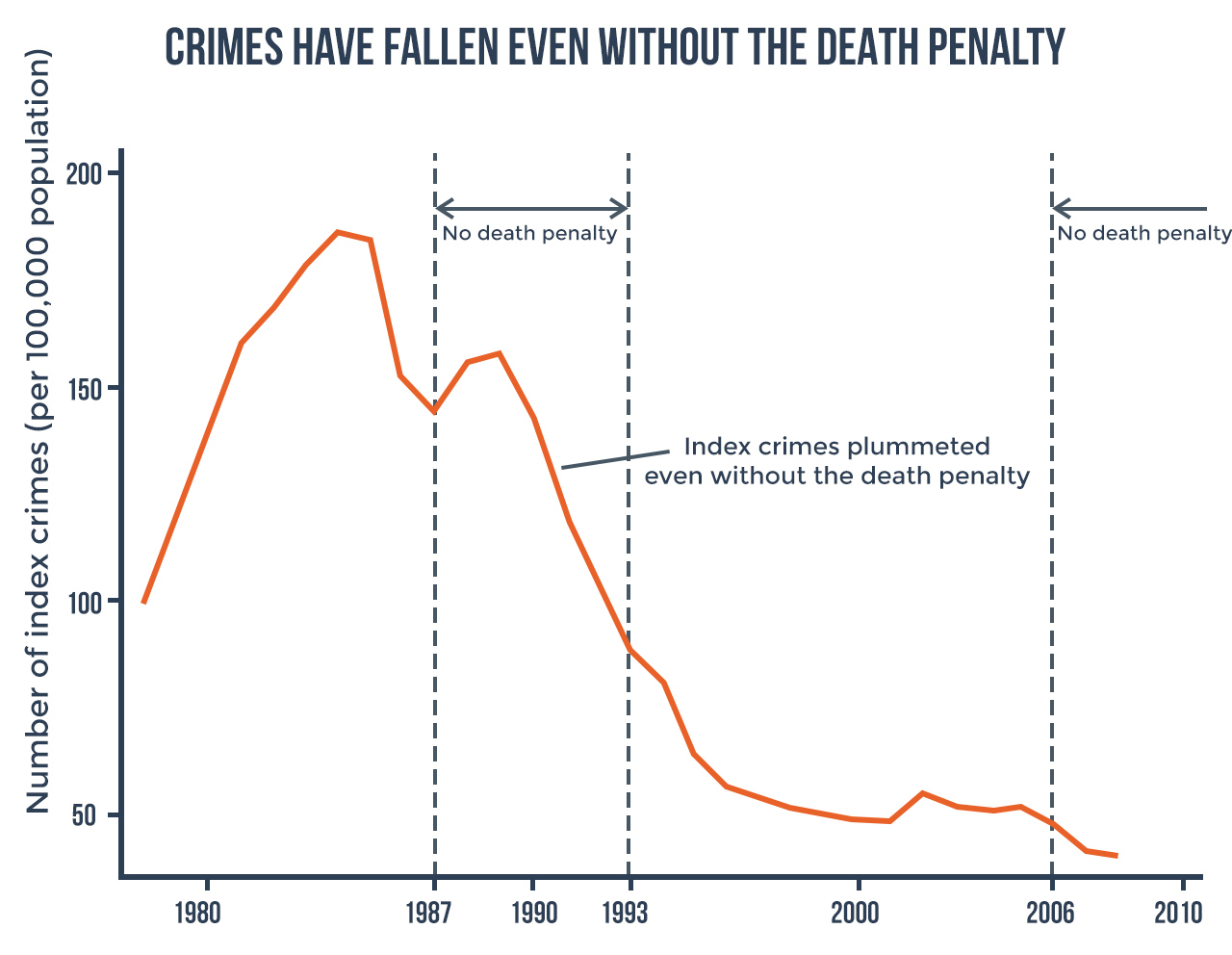

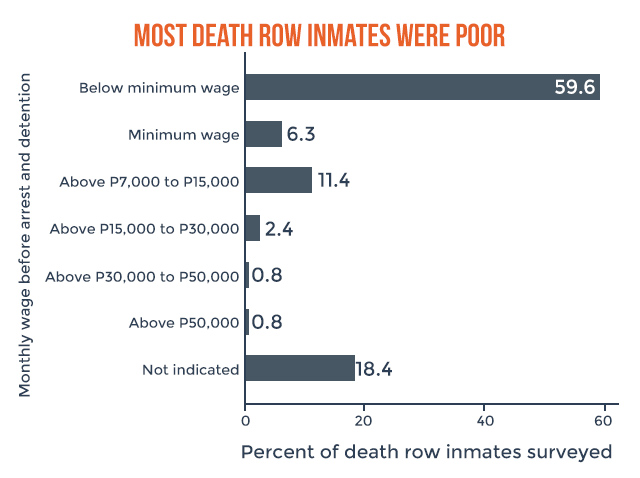

President Duterte’s decision to

President Duterte’s decision to

![Figure 2. Source: Nagin & Pepper [2012] Deterrence and the death penalty. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. Note: Data cover 1974 to 2009.](http://assets.rappler.com/612F469A6EA84F6BAE882D2B94A4B421/img/60646A644839483C8E3B23983E16B0C3/2-us-homicide-rates-20170210.jpg)

The call to resume the peace talks between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) is only right and just because their scrapping by President Duterte was premature, even as the NDFP Panel Chief Political Consultant and Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) guru Jose Maria Sison says he understands him. But this call should be accompanied by another call to resume the unilateral interim ceasefires that were also prematurely terminated first by the CPP and New People’s Army (NPA) leadership for the NDFP (not the other way around) and then soon after followed suit by President Duterte for the GRP. This was the casus belli, as it were, or what triggered the downward spiral of this whole peace process. This prematurity we had already discussed last weekend in an article “Urgent Motion for Reconsideration of the Ceasefire Termination,” forgive the court case terminology of a MR.

The call to resume the peace talks between the Government of the Republic of the Philippines (GRP) and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) is only right and just because their scrapping by President Duterte was premature, even as the NDFP Panel Chief Political Consultant and Communist Party of the Philippines (CPP) guru Jose Maria Sison says he understands him. But this call should be accompanied by another call to resume the unilateral interim ceasefires that were also prematurely terminated first by the CPP and New People’s Army (NPA) leadership for the NDFP (not the other way around) and then soon after followed suit by President Duterte for the GRP. This was the casus belli, as it were, or what triggered the downward spiral of this whole peace process. This prematurity we had already discussed last weekend in an article “Urgent Motion for Reconsideration of the Ceasefire Termination,” forgive the court case terminology of a MR.