On May 2, various government agencies banded together to hold a forum called #RealNumbersPH which sought to "correct" numbers about the war against drugs being used by media and human rights groups.

Journalists who attended the forum, however, noted that despite the number-filled infographics and presentations, no government official bothered to explain the origin of a very important number: 4 million drug addicts in the Philippines today.

This number is important because it provides the rationale for waging such a bloody campaign against illegal drugs. (EXPLAINER: How serious is the PH drug problem? Here's the data)

In fact, this number came from President Rodrigo Duterte himself.

It did not always use to be 4 million drug addicts. Back when he was running for president, it was only 3 million.

Let's trace the history of this "real number."

3 million addicts, late 2015 to June 2016– Duterte began using the figure of "3 million drug addicts" as a presidential candidate during campaign sorties, especially when Dionisio Santiago, a former Philippine Drug Enforcement Agency (PDEA) chief, was present. Santiago was then a candidate in Duterte's senatorial slate.

Duterte would even stop in the middle of his speech to call Santiago's attention so he could confirm the figure.

In mentioning this figure, Duterte would clarify that these were the statistics when Santiago headed PDEA. In other words, Duterte admits these are outdated numbers. Santiago headed PDEA from 2006 to 2011.

The Dangerous Drugs Board (DDB) says that in 2008, the only year when it released such data during Santiago's time, there were 1.7 million drug users nationwide.

3.7 million addicts, Duterte's first SONA, July 25, 2016 – After around a month in power, Duterte presented a new estimate of drug addicts – 3.7 million. Where did the 700,000 come from? It was just Duterte's "liberal" estimate.

"Give it a liberal addition. Maybe, make it [700,000]. So three million seven hundred thousand [3.7 million]. The number is quite staggering and scary," he said during his first State of the Nation Address.

4 million addicts, 2017 – By the year 2017, Duterte dropped the 3.7 million figure and now confidently declares there are 4 million drug addicts. The additional 1 million comes from the over 1 million surrenderers, as reported by the Philippine National Police.

For Duterte, it's safe to assume these surrenderers are drug addicts and can thus be combined with his original 3 million figure from Santiago.

Now an official number

The "4 million" figure has now found its way into government press releases and infographics. A #RealNumbersPH infographic declared "4 million users (as of April 20,2017)."

The infographic appeared to provide a "breakdown" of the 4 million but was in fact a list of other statistics which did not add up to 4 million.

This indicates that the administration is now using Duterte's figure as an official number to explain why his drug war is necessary.

It appears with other numbers from the PNP and PDEA – number of anti-drug operations, number of deaths under investigation, number of surrenderers.

But unlike these, the 4 million comes straight from the President and not from any specific study or field work. (READ: IN NUMBERS: The Philippines' war on drugs)

But, as pointed out by media, the 4 million estimate is very far from a figure from an actual survey. A DDB survey, conducted from January 1, 2015, to February 5, 2016, said there are 1.8 million drug users.

Though still a large number, this is significantly lower than Duterte's figure. Note that the DDB's term, "drug users," includes people who abuse drugs, are dependent, and who are drug addicts.

Thus, the figure for drug addicts is even smaller than 1.8 million.

No questioning Duterte's number

Understandably, government officials and Duterte's allies don't want to question his famous number.

When Dionisio Santiago attended a Malacañang event in December last year, he was asked by this reporter to confirm if he indeed gave Duterte the "3 million drug addicts" number – the number that started it all.

Santiago, who had been speaking to another reporter at the time, immediately changed his speaking tone, from carefree to angry.

He refused to answer the question and walked quickly away from reporters.

A PDEA official, interviewed by Reuters, even justified Duterte's "overestimation."

The President, he said, "just exaggerates it so we will know that the problem is very big.”

Journalists covering the police beat have asked the PNP to explain the 4 million figure, to which they would get the reply, "Sabi ng Pangulo (It's what the President said)."

However, PNP chief Director General Ronald Dela Rosa himself said the PNP prefers to use DDB's 1.8 million figure as a baseline so they would have “doable targets.”

According to an Inquirerreport, PNP operations head Chief Superintendent Camilo Cascolan had said, "The directive from the PNP chief is we will concentrate and focus ourselves on 1.8 million only."

This begs the question of why, despite PNP's use of the DDB figure, the "Real Numbers" forum insisted on Duterte's more questionable "4 million drug addicts."

In a December 2016 interview, Rappler's Maria Ressa confronted Duterte on his use of "3 million to 4 million drug addicts" in his speeches.

The President responded by saying not all drug addiction cases are reported anyway.

"Hindi naman lahat nare-report (Not all gets reported). And they do not admit it," he said.

Duterte side-stepped when Ressa asked if he planned to release his own data regarding his numbers. (READ: Data in the drug war: Why accurate numbers matter)

Government and some supporters of the President have bashed media for their reporting of "fake numbers" and have called on citizens to trust numbers released by government.

But with the President's own sketchy estimates, it might do well for government to be careful with its own numbers. – Rappler.com

![[Dash of SAS] Ana Santos](http://static.rappler.com/images/ana-santos-150.png) Dear Tito,

Dear Tito,

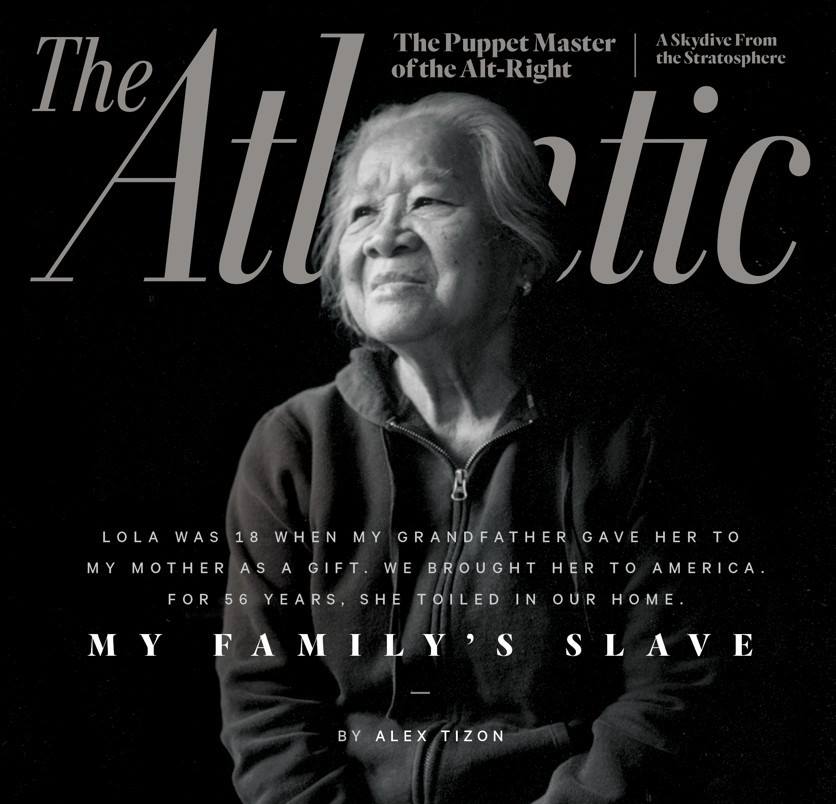

The posthumous publication of Pulitzer Prize-winning Filipino-American journalist Alex Tizon’s

The posthumous publication of Pulitzer Prize-winning Filipino-American journalist Alex Tizon’s