Almost everyone thinks Duterte is super powerful. Academic and media opinion says Duterte is overwhelmingly dominant, especially after the May 2019 midterm elections.

It would seem so, since no opposition senatorial candidate won. But only 3 of the 12 winners can be considered Duterte candidates; the rest won pretty much on their own. As shown in the 5 months since the May 2019 election, the opposition in the Senate is not limited to the minority.

In fact, the Duterte regime is a weak and incompetent regime. Its weakness begins with Duterte himself. He is impetuous, quick on the draw, makes policy decisions without prior consultation with his Cabinet, forcing his people to scramble to find out if what he’s pushing is legal or doable. This problem is compounded by his tendency to leave his people alone. As a result, the regime has no direction, his people contradict each other, factional battles are rife.

Although there is nothing more “Imperial Manila” than being in Malacañang, Duterte continues to maintain a “local” mindset. This is a problem if only because the national stage is vastly more complex than that of a provincial city. As Randy David wrote: “Mr. Duterte scoffs at the stubbornness of such complex systems as corruption, drug addiction and the communist rebellion. He seems to believe that if you kill all the drug addicts and drug pushers in the neighborhood, the fear that this creates would be enough to deter others from getting into the habit. Such astounding naiveté ignores the deep roots in society of the political economy of the drug trade.”

Change plus strong leadership are the main elements in Duterte’s populist persona. There has indeed been change and at least the image of strong leadership. Unfortunately Duterte’s “strong leadership” has undermined already weak institutions.

Change has been backwards – corruption is worst, trust in the legal system has weakened, provincial political clans have regained power at the expense of central government bodies. The economy and politics remain in the hands of a few families. Fortunately, the regime’s incompetence limits the damage.

Halfway through his term, it is now possible to analyze what the main outlines of Duterte’s “legacy” will be.

No anti-poverty strategy

Almost all analyses of the Duterte regime start with his drug war, with “extrajudicial killings.” I want to start with his identification with the poor, the “people.”

What is striking is that the administration does not have an anti-poverty strategy. This has been validated through specific policy decisions.

One of his recent decisions is vetoing an anti-endo (contractualization) bill after strong lobbying by business groups. Earlier, he also vetoed a bill which would have enabled the government to begin spending coco levy funds.

The budget for the housing sector has steadily decreased from P15.3 billion in 2017 to P5.5 billion in 2018 and then P3 billion in 2019. One of his populist measures, free tuition in state colleges and universities, is likely to end since the allocation for the Commission on Higher Education has been cut in the 2020 national budget.

While the economy continues to grow, there are disturbing signs.

Current account and balance of payments surpluses during the Aquino administration have turned into deficits. Government continues to underspend and fall below its deficit spending targets. Decelerating growth had given way to 5.5% GDP growth by the first semester of 2019, more than one percent below government targets. Duterte’s much-ballyhooed “Build, build, build” program for accelerated infrastructure investment appears to be stuck. By the middle of 2019, only 9 out of the 75 flagship infrastructure projects have begun construction.

What anti-corruption?

Duterte insists that anti-corruption is the centerpiece of his administration.

Instead, corruption scandals have hit the Department of Health, the Bureau of Customs, the Office of the Solicitor General, the Department of Tourism, the Philippine National Police, the Bureau of Corrections, the House of Representatives – enough to give the impression of what has been called a “feeding frenzy” in the national government.

Duterte himself has undermined his supposed anti-corruption thrust with statements justifying corruption. He has defended Solicitor General Jose Calida, the police, contractors in the DPWH, and himself.

On accusations of massive bank deposits to his and his families accounts, Duterte’s response was, "Ibig sabihin niyan marami akong kaibigan na mayaman." (It just means I have many rich friends.) Generous “friends” are not the only sources of Duterte largesse.

The 2020 budget proposal of the Executive show the Office of the President (OP) would be allocated P8.2 billion, way more than the P2.8 billion of then-president Bengino Aquino III in 2016. Between 2016 and 2017, confidential and intelligence funds over which the President has full discretion increased 218.5% and 293.7%. Duterte spent P2.5 billion in confidential and intelligence funds in 2017. Aquino, meanwhile, spent P2.98 billion during his entire six-year term.

Everybody points to Duterte’s high trust ratings. This is, in fact, not unusual for presidents. All of the past 5 presidents had high trust ratings except for Arroyo, and Erap Estrada’s numbers only fell in the couple of months before he was overthrown.

Duterte’s numbers have gone down a couple of times, in August 2017 and July 2018. While majorities support his drug war, over 90% of survey respondents consistently say suspects should be arrested alive; over 75% say they fear they or someone they know will be the next EJK victim; 10% or less say they believe the police when the police say a suspect was killed because “nanlaban”.

Part of the reason Duterte remains popular is that the opposition has focused on responding to extrajudicial killings and other human rights violations, to distortions of the law to go against opposition figures, to Duterte’s shoot-from-the-hip style of governance. These are all valid issues, and work on them has to be continued.

Beyond liberal democracy

But together these issues come across as defending liberal democracy. It is precisely the people’s unhappiness with liberal democracy which is at the core of Duterte’s populist support. If the opposition comes across as mainly defending liberal democracy, this is not going to make a dent in Duterte’s popularity.

Opposition communications have to focus more on Duterte’s being pro-establishment. It’s not just that that he does not have an anti-poverty strategy, one could argue that he is actually anti-poor. The main target of his “war on drugs” has been almost completely the poor. Even the anti-tambay (socializing outside of peoples’ homes) campaign is anti-poor since urban poor do not have living rooms where they can socialize. To link these policies to Duterte himself, more attention has to be focused on corruption, in his government and his family.

One of the indications of doubts about Duterte’s political longevity is that there is already speculation about who would replace him after the 2022 presidential election. The pattern from the past has been that a year before the presidential election, political energies would be focused on strong candidates and away from the incumbent.

It is too early to say that Duterte has become a lame duck President, but who replaces him has, as early as now, been a preoccupation. If Duterte cannot come up with a strong candidate to replace him, he may try to resort to extra-constitutional means.

Duterte has to find an electable successor. Many of Duterte’s people look to Davao City Mayor Sara Duterte Carpio. Mayor Sara burst into the national scene when she engineered the removal of Pantaleon Alvarez as Speaker of the House in 2018. She actively campaigned for her senatorial slate in the 2019 election and is credited with having helped secure the victory of 9 senators.

In truth, winning candidates had either considerable political capital to begin with or massive government resources backing them up. Two leading figures of her party lost in embarrassing landslides in local elections in her own bailiwick: Anthony del Rosario and Antonio Floirendo Jr. lost to Pantaleon Alvarez!

Sara in 2022?

Sara Duterte’s election campaign strategy in 2019, focusing on winning the support of local political clans, could backfire in 2022.

In 2019, local clans understood that they would continue to be dependent on Malacañang largesse for another 3 years. In 2022, they could place their bets on a strong candidate and reap bigger benefits if he/she won. Competing candidates for the presidency will have, if not equal, reasonably strong chances of winning the support of local clans.

A Sara Duterte victory in 2022 will depend partly on her father’s continuing popularity and endorsing power. Even if he retains his trust ratings it is still doubtful that his endorsement will be enough to elect his successor. Only one (Cory Aquino) of the last 5 presidents before Duterte (Cory Aquino, GMA, Ramos, Estrada, Noynoy Aquino) succeeded in securing the election of their chosen candidates.

We probably have to suffer through a few more years of Duterte’s inanities unless we’re lucky (I won’t say how), and he’s not. The big players could begin to actively work against him.

But these are all “ifs”; we can’t plan on the basis of “ifs.” But by 2021 at the latest, Duterte will be a lame duck president. Unless the strongest possible successor is his own candidate, local political clans will gravitate toward other presidential candidates.

Our responsibility is to work hard to make sure that the winning presidential candidate is a real alternative to Duterte-style politics and economics, not another trapo taking advantage of anti-Duterte sentiment. – Rappler.com

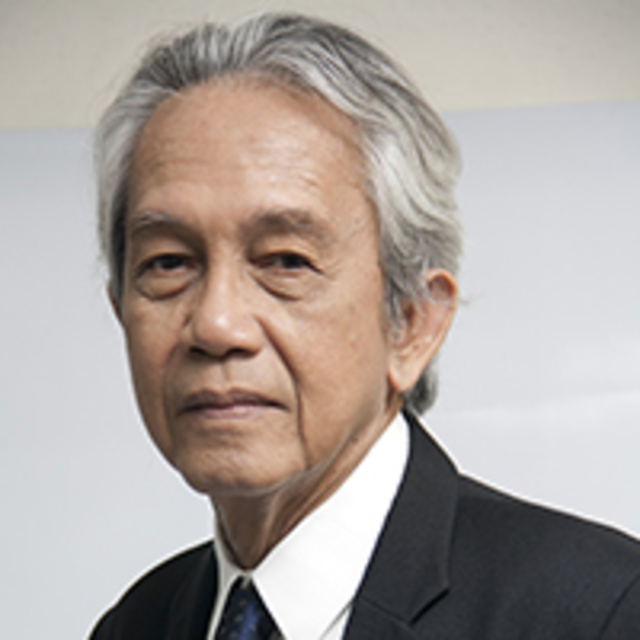

Joel Rocamora is a political analyst and a seasoned civil society leader. An activist-scholar, he finished his PhD in Politics, Asian Studies, and International Relations in Cornell University, and had been the head of the Institute for Popular Democracy, the Transnational Institute, and the Akbayan Citizens’ Action Party. He worked in government under former president Benigo Aquino III as the Lead Convenor of the National Anti-Poverty Commission.