The Supreme Court’s majority opinion on the burial of the late dictator Ferdinand Marcos at the Libingan ng mga Bayani validates once more the conflicting themes of the country’s postwar political experience: authoritarianism and democracy.

The SC decision likewise reveals the unfolding realignment of the various forces in the political spectrum, as shown by the political statements of leaders of varying political persuasions.

This perceived realignment of political forces would likely define the course of political developments in the coming months, as the perceived autocratic forces pursue an authoritarian agenda that centers on the political redemption of the Marcoses and their return to political power.

On the one end, authoritarianism, as represented by the disparate political groups and personalities identified with the failed constitutional authoritarian regime of Marcos, is seen to be staging a major comeback that goes beyond the unsuccessful vice presidential run of Ferdinand Jr. in the last elections.

This perceived comeback is illustrated in the autocratic tendencies to sanitize, or even justify the widespread world-class kleptocracy, or corruption, plunder, massive human rights violations and other abuses committed by and associated with the Marcos regime.

On the other hand, democracy, as represented by various political groups that have worked for the restoration of democracy and have been working continuously for the strengthening of those democratic institutions and processes, is talking a backseat to give way to these authoritarian tendencies. (READ: Duterte to suspend writ of habeas corpus if 'forced')

Democracy, which clings to the time-honored precept of rule of law and adheres to the strong democratic institutions and processes, and its associated concepts are being battered to give way to what seems to be a global resurgence of authoritarianism.

The old school core values of freedom and respect associated with democracy are being challenged to make them appear irrelevant and unsustainable.

Marcos-Arroyo informal alliance

The SC decision on the Marcos burial has triggered shockwaves in public opinion, redrawing the emerging realignment of political forces in the political spectrum.

Forces of authoritarianism – former president and now Deputy Speaker Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo and her ilk; Ferdinand Jr. and Imee Marcos and their rabid supporters; and President Rodrigo Duterte and his coalition – have forged an informal alliance to press for an agenda with authoritarian tendencies.

They are joined by a group of Supreme Court magistrates, who always vote as one when it comes to issues involving the authoritarian agenda, and some civil society groups that support authoritarian tendencies.

Mrs. Arroyo and the Marcoses were among the financial backers of the Duterte presidential run. The President is observed to have been taking taken steps to pay his political debts to the Arroyo and Marcos camps.

At the moment, the authoritarian agenda is on the exculpation of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, his family, and cohorts from any responsibility or complicity of all abuses they had committed during the martial law era, the renewal of their tattered global public image, and their final political redemption through Ferdinand Jr.

They have yet to take the initiative to dismantle the democratic structures and processes that have been the result of 30 years of restored democracy and replace them with a new political system supportive of strongman’s rule. But they appear to be moving to the direction to lay down the preconditions to reimpose authoritarianism.

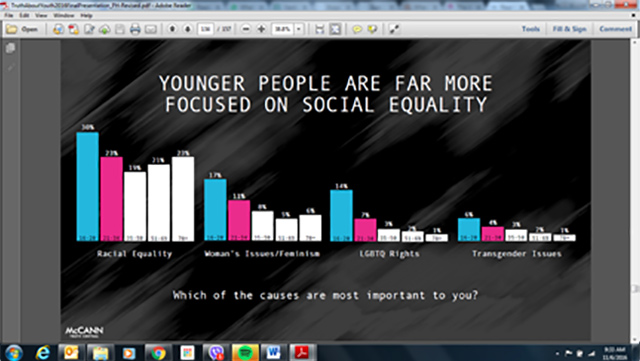

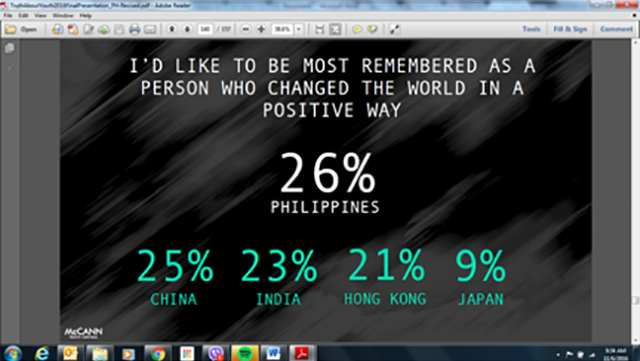

They seem to have been emboldened by Ferdinand Jr.’s strong showing in the last presidential polls, where he lost to Vice President Leni Robredo by slightly over a quarter of a million votes. They believe that the authoritarian agenda is within reach, as indicated by the political support of the millennials (18-35 year old) to the dictator’s son.

Although weakened considerably by the losses of its candidates (they had two presidential candidates, who divided the votes of the democratic constituency) and Duterte’s plurality victory, the democratic forces have continued to oppose those autocratic tendencies, as indicated by their vehement objection and opposition to the Marcos burial at the Libingan and any political comeback by the Marcoses.

They are likely to consider and come out with every conceivable way to oppose the authoritarian agenda, although they are likely to stick to the rule of law and the legal processes, which they have championed for the past three decades.

Authoritarian coalition

The authoritarian coalition, led by no less than the President, would continue to push for their agenda of political redemption for the Marcoses.

The clash of these contending forces is expected to intensify by next year.

This is the coalition perceived to push further its luck by moving heaven and earth to push the Presidential Electoral Tribunal (PET) to reverse the political victory of Robredo and award the political victory to rival Ferdinand Jr.

Even Duterte has strongly indicated the possibility of Ferdinand Jr. to take over the presidency during his term of office. The democratic forces have been resistant to the prospect of Marcos comeback.

Citing the implications of the decision on Marcos burial at the LIbingan, some quarters have likewise expressed apprehension that the Supreme Court could rule the return to the Marcoses of all confiscated ill-gotten wealth and the jewelry pieces of former first lady Imelda Marcos.

Journalist Mike Suarez said in his Facebook account that the Marcoses could pick from the SC decision “the cue” to file those cases before the High Court. “After all, as the SC ruling went, there has been no criminal conviction. Ergo the seizures were wrongful,” Suarez said.

From all indications, the SC decision on the Marcos burial would lead to a more problematic situation. The promised national reconciliation and ensuing healing is more rhetoric than actual. – Rappler.com

Traffic congestion seems to have worsened more than a year since my original "

Traffic congestion seems to have worsened more than a year since my original "

There’s no way President Duterte can escape being dragged into the controversy provoked by the sudden,

There’s no way President Duterte can escape being dragged into the controversy provoked by the sudden,

My voice against the Marcoses has been loud since the election days, making me gain virtual enemies and lose friends along the way. Nonetheless, I don’t regret anything, not a single moment of it. I am proud to say that I’m standing up for nothing but the truth. Besides, thanks to all the people who fought for our democracy, you and I are freer to voice out our opinions without ending up raped, tortured, and killed, which is a privilege that more often than not, we tend to take for granted. Hence, might as well use it for something worthwhile.

My voice against the Marcoses has been loud since the election days, making me gain virtual enemies and lose friends along the way. Nonetheless, I don’t regret anything, not a single moment of it. I am proud to say that I’m standing up for nothing but the truth. Besides, thanks to all the people who fought for our democracy, you and I are freer to voice out our opinions without ending up raped, tortured, and killed, which is a privilege that more often than not, we tend to take for granted. Hence, might as well use it for something worthwhile.

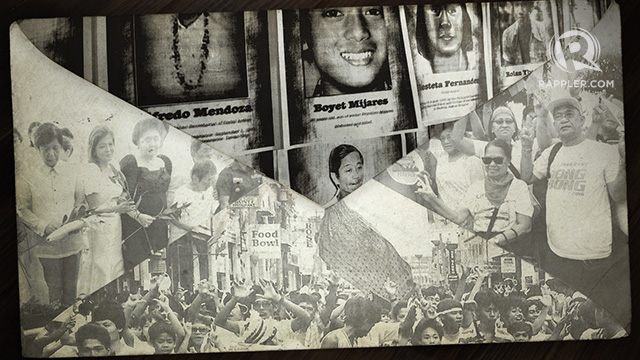

[This is an unfinished essay. I designed this so that others who were victims or were severely affected by the Marcos dictatorship, can add their stories. My hope is that if this pulls through we will have a site where the different voices that were silenced or eliminated by the dictator Marcos can be read by those wanting to know what happened during those 15 terrible years. Many have complained that one reason the Marcoses were able to resurrect themselves politically is that we do not have enough stories to share with people, especially the younger generation. This is an attempt to build that cache of stories.]

[This is an unfinished essay. I designed this so that others who were victims or were severely affected by the Marcos dictatorship, can add their stories. My hope is that if this pulls through we will have a site where the different voices that were silenced or eliminated by the dictator Marcos can be read by those wanting to know what happened during those 15 terrible years. Many have complained that one reason the Marcoses were able to resurrect themselves politically is that we do not have enough stories to share with people, especially the younger generation. This is an attempt to build that cache of stories.]

The rights of lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) persons have seen progress within the UN, with resolutions aimed at protecting and promoting these rights being adopted in recent years. But the Philippine government apparently does not want to involve itself.

The rights of lesbian, bisexual, transgender, intersex and queer (LGBTIQ) persons have seen progress within the UN, with resolutions aimed at protecting and promoting these rights being adopted in recent years. But the Philippine government apparently does not want to involve itself.

I can still remember being in the student council in the ‘90s talking to student leaders who had come before us.

I can still remember being in the student council in the ‘90s talking to student leaders who had come before us.