![]() (READ: Part 1: Time for pro-democracy forces' agenda)

(READ: Part 1: Time for pro-democracy forces' agenda)

The 1986 EDSA People Power Revolution was the game-changing political upheaval that led to the restoration of Philippine democracy and the revival of democratic institutions and processes. Cornered like scalded cats, Ferdinand Marcos, his family, select relatives, and friends fled on the night of February 25, 1986, and went into a 5-year exile in Honolulu to escape the collective wrath of the Filipino people.

Meanwhile, President Corazon Aquino took the country to the tortuous and arduous task of rebuilding the country from the morass created by the Marcos dictatorship. She battled at least 7 military coups, and regained the trust and confidence of the international community. The Cory government took major steps to dismantle the authoritarian structures and destroy the tendencies to bring back the authoritarian system.

The Aquino government scrapped the 1973 Constitution and replaced it with the 1987 Constitution, replaced en masse local officials identified with the dictatorship, retired overstaying military generals, and established the PCGG to run after the ill-gotten wealth of the Marcoses, relatives, and ilk.

It abolished the Batasang Pambansa, the rubber stamp legislature created by Marcos, called free, honest, and credible new elections under the new Charter, and reestablished Congress, the members of which were popularly elected. She reorganized the Commission on Elections, Commission on Audit, Civil Service Commission, and Commission on Human Rights, the 4 constitutional offices under the 1987 Constitution.

Over the years, the succeeding governments had worked for the creation of the Office of the Ombudsman, Philippine National Police, and Bangko Sentral ng Pilipinas; the professionalization of the Armed Forces of the Philippines and PNP; and abolition of state firms that propped up the dictatorship and their replacement with accountable and transparent government-owned and controlled corporations (GOCCs).

But the soft treatment, inability, and failure of the Aquino administration and its successors to get rid of the Marcoses or put the final nail on their political coffin appears to have become a major problem over the last 30 years.

Somewhere, sometime, and somehow, the Marcoses continue to haunt the country. They did not hesitate to use their fabulous loot to revise history, reinvigorate their networks, and use the democratic system they earlier destroyed to stage a political comeback.

Authoritarian, democratic forces

The rise of the political forces with authoritarian tendencies had manifested during the run-up to the 2016 presidential elections. Just before Bongbong Marcos announced his intention to seek either the presidency or vice presidency, political forces identified with his late father’s rule started forming and solidifying.

This was not the end though. The Marcos camp, led by Ilocos Norte Governor Imee Marcos, entered into a tactical alliance with the Duterte forces despite Duterte’s decision to have Senator Alan Peter Cayetano as his running mate. Although the young Marcos ran as an independent, Duterte tilted towards him as if he were his running mate.

Later, the camp of former president Gloria Macapagal-Arroyo, through husband Jose Miguel Arroyo, joined the Duterte-Marcos alliance, forming the triumvirate of authoritarian forces in the country. The Marcos and Arroyo camps were reputed to have provided enormous resources for Duterte’s presidential campaign.

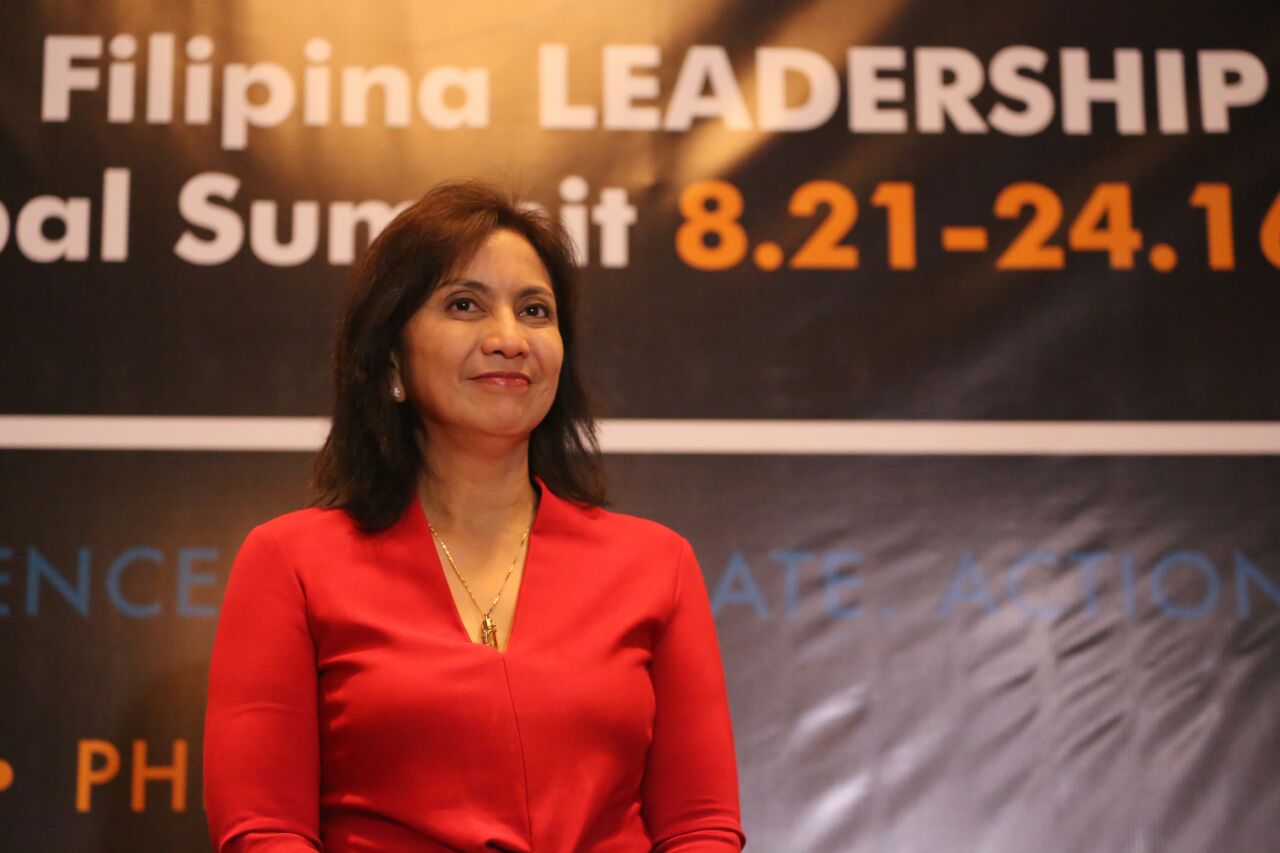

The pro-democracy forces were resigned to accept Duterte’s election, as they could only express regret over Senator Grace Poe’s insistence to run for president and divide the votes of the democratic constituency. Only Mrs Robredo’s election as vice president could assuage their combined feelings of frustration and rejection.

But when the incidence of extrajudicial killings (EJKs) took an upswing and the Supreme Court ruled in favor of the release of Mrs Arroyo from imprisonment, the pro-democracy forces felt uneasy, forcing them to abandon their wait-and-see stance. The unrestrained but careless statements of the pugnacious president were factors too.

When the Supreme Court ruled, favoring the burial of Marcos at the Libingan ng Mga Bayani and the Marcos family implemented their planned stealth burial, the battle lines appeared to have been drawn. The camps of Duterte, Marcos, and Arroyo are now perceived to have been in a conspiracy.

The pro-democracy forces would take to the streets to raise their objection to such conspiracy. Such objection was already shown by two subsequent and successful mass actions on November 25 and 30. More protest actions are expected in the coming days. A new protest action was held on December 10.

Meanwhile, Mrs Robredo has resigned abruptly from the Duterte Cabinet, triggering expectations that she would have to take the mantle of leadership of the pro-democracy movement and the political opposition since she is the current highest elected political leader.

Judging from her statements and body language, Mrs Robredo does not seem to be one to flinch from a fight and could be assumed to lead the massive protest movement that could escalate by the first quarter of 2017.

Mrs Robredo’s departure from the Cabinet could also mean providing a face or inspiration for the pro-democracy movement. Her reputation as public official has remained untainted although she has been the subject of insidious black propaganda. She has developed her own charisma, seemingly inspiring democratic forces to take her as their leader.

Meanwhile, the aurthoritarian camp is reported to have been moving to form Kilusang Pagbabago, a purported citizens’ movement no different from the Kilusang Bagong Lipunan (KBL) of the Marcos dictatorship. This purported citizens’ movement, according to its prime mover, Cabinet Secretary Leoncio Evasco, seeks to put administration supporters under a single roof, making it the KBL of Duterte.

Evasco was reacting to the embarrassment of the Duterte and Marcos camps, when the Duterte Youth, which is similar to Hitler Youth (Hitler Juven), came out for the first time in the November 25 and November 30 mass actions with hardly a handful of members, who were not even youthful in looks. They were subjects of public ridicule in social media.

Democratic agenda

Over the last 3 decades, the democratic cause has reshaped, as shown by the varying situation, but its fundamentals have hardly altered. The pursuit of truth and justice has been the central theme of pro-democracy forces. Moreover, economic wellbeing as shown by jobs and food on the table is a fundamental objective. Furthermore, the respect of human rights of every individual is paramount.

The authoritarian forces likewise speak of those objectives, or something close to those noble goals. But they could not hide their disdain for the established democratic traditions and structures, their contempt for the rule of law and human rights, and their intention to revise history to show the Marcos authoritarian experiment was successful. They never speak of keeping the democratic system, but insist on breaking the established democratic order ostensibly to bring the country to what they regard “a path of economic progress.”

![]()

For instance, the current administration speaks of federalism, which calls for the adoption of a federal form of government to replace the current unitary government. Deep apprehension has been expressed by several political quarters, which view federalism as a Trojan horse that could lead to a weakened central government, thus strengthening those authoritarianism tendencies.

The anti-drug war serves as a convenient platform for those authoritarian tendencies. By continuously harping – or exaggerating – that the country has become a narco-state, the current political leadership has been virtually saying that it is now incumbent to pursue extrajudicial killings (EJKs) for reason of national security. In its limited reasoning, the political leadership is virtually saying that pursuing EJKs is a matter of self defense.

The November 25 and November 30 mass actions have confirmed two things: first, the existence of a critical mass of warm bodies to comprise the pro-democracy movement; and second, the emergence of young people, or millennials, as a new force to reckon with.

Hence, the democratic agenda encompasses 3 major areas: politics, education, and governance.

On the political sphere, the pro-democracy forces should continue, sustain, and step up the protest mass actions to stop the authoritarian agenda from further taking root under the Duterte government. It should take steps to stop any attempt to manipulate the democratic process leading to a victory of the young Marcos in his electoral protest and his assumption of the vice presidency.

Reviving the “parliament of the streets” would not only complement the battles in the so-called “parliaments of social media” in those skirmishes to win the hearts and mind of the public. The parliament of the streets seeks to counter inroads in Congress and other forums to railroad public acceptance of the authoritarian agenda, which includes disrespect of basic human rights and the proposed legislation to lower the age of criminal liability to 9 years and the restoration of death penalty.

Both the parliaments of the streets and social media exert what has been regarded as “pressure politics,” which seeks to influence the democratic institutions and processes to behave in the generally accepted democratic manner. Moreover the two parliaments, which serve as unofficial legislators, seek to check abuses against the democratic principles and bring to public attention these abuses.

On the educational sphere, the pro-democracy forces, which have been transformed into a citizens’ movement, should take steps to stop efforts to revise history, rehabilitate the Marcos dictatorship, and sanitize the public image of the young Marcos, who is being groomed by the authoritarian forces to replace Duterte.

They have come out with a plan forming teams of anti-Marcos adherents to go to major cities and even rural areas to explain the Marcos legacy of world class kleptocracy, massive human rights violations, and crony capitalism. In fact, teams have already formed for barnstorming visits.

But this would not be enough without pursuing the inclusion of the Marcos dictatorship in the history books. Over the last 3 decades, public and private educators have succeeded to pursue the “demarcosification” of textbooks and other reference materials. But they have merely scrapped statements and paragraphs hailing Marcos as sort of hero or demigod in textbooks of elementary and high school students.

They have yet to include pertinent materials about the Marcos legacy. They have yet to explain what the Marcoses and their ilk did to the country, particularly their greed. The issues of crony capitalism, kleptocracy, and human rights violations have to be fully explained to them.

Democratic governance

Over the past 3 decades, the restored democracy has been functioning well as indicated by the performance of democratic structures and institutions. The Armed Forces, the judiciary, and mass media are among the institutions that reflect sustained democratic governance.

The AFP has shown its capacity to reform to become what the 1987 Constitution has envisioned – the defender of the Republic and “protector of the people.” From a highly politicized instrument of the Marcos dictatorship, the AFP has transformed to become an institution of professional soldiers, whose loyalty is not to the person in power but the Constitution.

Hence, the democratic agenda should step up efforts of the pro-democracy movement to stop all attempts to coopt the AFP to become part of the emerging authoritarian regime. The democratic forces should stop presidential overtures to make the AFP part and parcel of the anti-drug war. Its identity as an institution of constitutional soldiers should remain intact.

The AFP has the virtual monopoly of arms, but the pro-democracy movement should stop the use of those arms against the people the AFP has sworn to defend and protect. The democratic agenda should stress a full campaign to emphasize the “protector of the people” doctrine to all soldiers.

The democratic agenda should stop authoritarian incursions on the independence and integrity of the judiciary and mass media, two institutions which serve as the bedrock of restored democracy. Without these two institutions, the restored democracy could be regarded as big failure. – Rappler.com

![]()

The 2016 national elections seem so far away in distant memory now; but the official statistics on the elections only recently released and analyzed, should spur the country to think deeply about its democratic future.

The 2016 national elections seem so far away in distant memory now; but the official statistics on the elections only recently released and analyzed, should spur the country to think deeply about its democratic future.

It was an overcast, drizzling Saturday afternoon when my parents and I decided to go to the Libingan ng mga Bayani (LNMB) to visit the grave of my brother, 2nd Lieutenant Julian Omar V. Advincula of the Philippine Navy (Marines).

It was an overcast, drizzling Saturday afternoon when my parents and I decided to go to the Libingan ng mga Bayani (LNMB) to visit the grave of my brother, 2nd Lieutenant Julian Omar V. Advincula of the Philippine Navy (Marines).

CUSCO, Peru - The Philippines, with its 7,107 islands, can be considered part of the Pacific Islands and of Oceania. From Taiwan, the big bulk of the great Austronesian migration may actually have passed through the Philippines, and many of the languages from Madagascar to Easter Islands are similar to our own: when you call for “tulong” in Indonesia, they will understand. We share with Austronesian peoples root crops like gabi and ube; our knowledge in marine navigation; our intimacy with the sea.

CUSCO, Peru - The Philippines, with its 7,107 islands, can be considered part of the Pacific Islands and of Oceania. From Taiwan, the big bulk of the great Austronesian migration may actually have passed through the Philippines, and many of the languages from Madagascar to Easter Islands are similar to our own: when you call for “tulong” in Indonesia, they will understand. We share with Austronesian peoples root crops like gabi and ube; our knowledge in marine navigation; our intimacy with the sea.

Living on the edge poses risks and dangers. But it also enables a sense of adventure that sometimes propels meaningful change even in our policies and practices. Much like the thrill of intimacy - however momentary - especially after enduring loveless, sexless or even violent unions, which are as yet expensive and embarrassing to unmake.

Living on the edge poses risks and dangers. But it also enables a sense of adventure that sometimes propels meaningful change even in our policies and practices. Much like the thrill of intimacy - however momentary - especially after enduring loveless, sexless or even violent unions, which are as yet expensive and embarrassing to unmake.

Due to the obvious differences in terms of context, power, and global significance, it is difficult to compare the current President of the Philippines, Rodrigo R. Duterte, and the US President-elect Donald J. Trump (known to their supporters as “Digong” or “Rody” and “the Donald”, respectively). Also, Duterte has been in power since late June 2016, while Trump will be inaugurated only early next year. Yet, there is a compelling reason to discuss the two politicians together. Both Duterte and Trump have caused outrage, both locally and globally, with their offensive and vulgar communication styles.

Due to the obvious differences in terms of context, power, and global significance, it is difficult to compare the current President of the Philippines, Rodrigo R. Duterte, and the US President-elect Donald J. Trump (known to their supporters as “Digong” or “Rody” and “the Donald”, respectively). Also, Duterte has been in power since late June 2016, while Trump will be inaugurated only early next year. Yet, there is a compelling reason to discuss the two politicians together. Both Duterte and Trump have caused outrage, both locally and globally, with their offensive and vulgar communication styles.

So what if she's not a journalist?

So what if she's not a journalist?