Six months ago, Rodrigo Duterte and his faction of the ruling class won the elections by riding on the wave of revulsion against then President Benigno Aquino, his faction of the ruling class, and the social order they defended.

Six months ago, Rodrigo Duterte and his faction of the ruling class won the elections by riding on the wave of revulsion against then President Benigno Aquino, his faction of the ruling class, and the social order they defended.

Hoping to advance their own narrow interests, Duterte tapped the widespread dissatisfaction and feeling of insecurity fueled by the liberals’ elitist, neoliberal policies: their rejection of workers’ demands for regular jobs and better pay; their failure to provide dignified social services for all; and their indifference to the lower classes’ yearning for security.

Like so many populists before him, Duterte capitalized on people’s hopes and aspirations by vowing to advance the interests of the oppressed – while also simultaneously vowing to advance the interests of their oppressors. He promised to end “contractualization,” expand social services, and stamp out criminality – while also promising businesses cheap labor, lower taxes, and continued growth.

He even installed progressives in Cabinet and voiced support for a number of progressive ideas.

But, as so many Caesars and Bonapartes before him have realized, no ruler could give to one class without taking from the other: Ending contractualization means making labor less cheap for capital. Expanding social services requires compelling the rich to pay more taxes. Stamping out criminality requires pursuing social reforms which, in turn, entails challenging the prerogatives of the mighty.

Like so many populists before him, Duterte was forced to choose sides, and today it is clear whose side he has chosen.

Instead of improving the lives of workers, he has put his foot down on wage increases, and he is set to issue a so-called “win-win” solution to contractualization that actually sells workers down the river.

Rather than increasing taxes on the rich to expand social services, he is pushing for “tax reforms” that have been lauded by the market fundamentalist think-tank Foundation for Economic Freedom for seeking to reduce the tax obligations of those in the upper brackets without significantly increasing social spending.

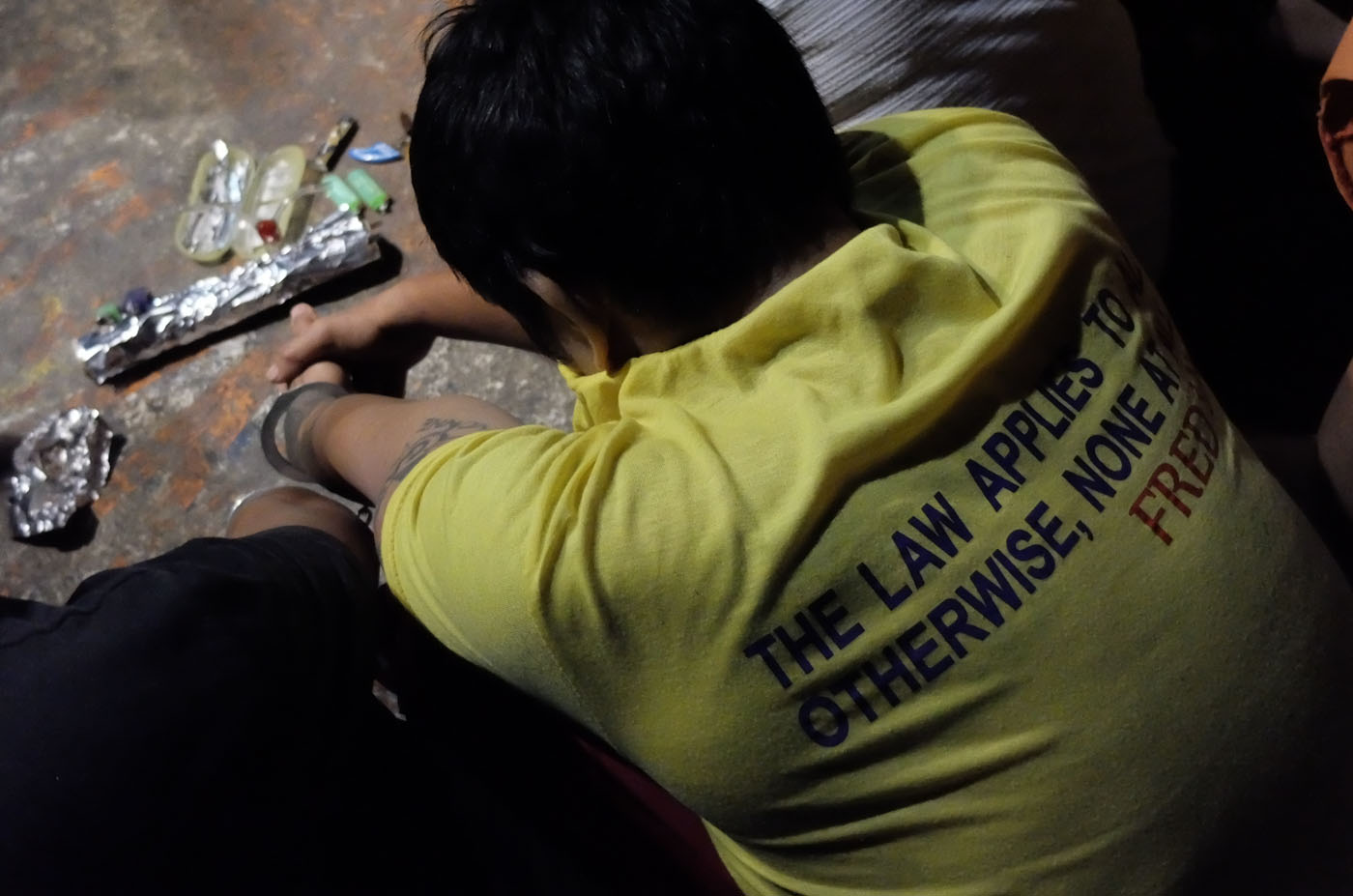

And instead of challenging the prerogatives of the wealthy to enact the redistributive measures needed to strike at the root of the drug problem, he has chosen to take a short-cut and wage a ‘war on drugs’ that has so far resulted in the death of over 5,000 people – nearly all of them from the ranks of the poor and unemployed.

In addition, he is pushing for constitutional revisions and other measures that are likely to make it even harder to undertake redistribution.

In short: instead of choosing the side of the people, Duterte has predictably chosen the side of capital. With his own actions and omissions, he has exposed himself for what he was from the beginning: an enemy – rather than an ally – of the oppressed. Far from being the first “socialist” President, he has proven himself to be yet another ruthless reactionary.

This in large part explains why the spectre of fascist rule now hangs over us like a dark cloud: Having chosen to side with the oppressors, Duterte can now only fall back on brute force to contain the discontent and resistance that is likely to grow in the face of his treachery. Hence, his threat to suspend the writ of habeas corpus; his push for the death penalty; his attempt to condition the minds of the people into thinking that dictatorship is “heroic” by giving Marcos a hero’s burial; his “Kilusan para sa Pagbabago” project to organize a fascistic grassroots movement to defend his regime; and his efforts to cultivate the loyalty of state forces by coddling them and shielding them from prosecution.

Faced with these developments, the ruling-class faction represented by the Aquinos are now also trying to ride on the wave of the growing opposition to Duterte in the hope of returning to power. They too are now also tapping the growing dissatisfaction and feeling of insecurity fueled by Duterte’s elitist, anti-poor, and increasingly draconian policies. And they too are now trying to capitalize on the frustrated hopes and dreams of the people in order to advance their own factional, oligarchic interests.

Mobilizing all the resources and advantages they command as displaced elites, they are now moving to position themselves again as the only “democratic” and “realistic” alternative to fascist rule.

To do this, they are portraying Leni Robredo as a reformist champion of the poor despite her refusal to break with cacique elitists like Aquino/Roxas and despite her own support for the same neoliberal anti-poor policies that Aquino championed and Duterte continues to pursue.

Harking back to the Aquino years as a kind of mythical “golden age” in the Philippines, they are now trying to limit our horizons and narrow our imaginations by trying to persuade us that a return to the yellow past and a restoration of yellow rule is the best we can possibly hope for.

In short, they are now moving to hijack our burgeoning movement for democracy again – just as elites displaced by Marcos did in 1986 and just as elites displaced by Estrada did in 2001.

But we do not have to allow them to steal our dreams again.

We must say no to both Duterte/Marcos and Robredo/Aquino because, though they clash in their styles, both camps are actually united behind a common goal: perpetuating elite rule. We must refuse to march behind either the bloodied banner of the fascist incumbents and the jaundiced yellow flag of the (il)liberal trapo opposition because, though they disagree over the means, both ultimately share the same aims: to keep us in chains. Though we must of course march alongside Robredo in her opposition to Duterte’s fascist measures, we must refuse to march behind her unless she breaks decisively with both the pro-Duterte and anti-Duterte elites and denounces neoliberalism and elite rule.

Instead of remaining imprisoned in their false choices, we need to fight for a different–because truly democratic–society. Instead of remaining chained to our masters and marching behind their tattered flags, we must declare our independence and march behind an alternative banner: the red flag of socialism. Instead of returning to the past and remaining trapped in this vicious cycle, we can break free and create a different, more hopeful future.

We have nothing to lose but our chains. – Rappler.com

Herbie Docena is a PhD candidate in Sociology at the University of California, Berkeley who is now back in the Philippines. He was involved in mobilizing students as editor in chief of the Philippine Collegian during the EDSA Dos uprising in 2001 and he is currently helping organize the Socialist Circle, a newly-formed anti-capitalist, anti-patriarchal, and anti-fascist group committed to creating spaces for exploring and advancing socialist, feminist, and radically democratic alternatives to the present order.

Despite nearly four years living in the Philippines, my palate never quite grew accustomed to what seemed to me to be sugar-filled spaghetti sauce. But my taste buds' passion for halo-halo and whatever else might be on my merienda menu is another matter.

Despite nearly four years living in the Philippines, my palate never quite grew accustomed to what seemed to me to be sugar-filled spaghetti sauce. But my taste buds' passion for halo-halo and whatever else might be on my merienda menu is another matter.

![[Dash of SAS] Ana Santos](http://static.rappler.com/images/ana-santos-150.png) If you’re a parent of a teenager like me, you probably want to have “The Drug Talk” with your kid.

If you’re a parent of a teenager like me, you probably want to have “The Drug Talk” with your kid.

When I think of childhood, I think of family picnics and pets. I think of early morning grocery runs and lazy afternoon walks. I remember playing with friends and learning my lessons in school. I remember Christmas morning magic and gorging on fruits in the summer. I remember weekly catechism classes before mass. My childhood was idyllic; it was normal.

When I think of childhood, I think of family picnics and pets. I think of early morning grocery runs and lazy afternoon walks. I remember playing with friends and learning my lessons in school. I remember Christmas morning magic and gorging on fruits in the summer. I remember weekly catechism classes before mass. My childhood was idyllic; it was normal.

What will you eat or drink during the holiday season?

What will you eat or drink during the holiday season?

I worked for almost a decade in the UN, focused on international development policy, including the governance of aid. And the international development assistance system can certainly be critiqued in many ways.

I worked for almost a decade in the UN, focused on international development policy, including the governance of aid. And the international development assistance system can certainly be critiqued in many ways.

In a country that has been so vocal about protecting human rights and promoting social justice, silence means more deaths. As of November, almost

In a country that has been so vocal about protecting human rights and promoting social justice, silence means more deaths. As of November, almost

Since 2002, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been in power in Turkey. He was prime minister for 11 years till 2013 and then in 2014 became president of Turkey. During this period, his ruling party could change the picture of Turkey to a modern Islamic country. Turkey GDP has grown from a lowly 200 billion USD in 1995 to over 800 billion USD in 2014. The direct investment in Turkey reached to 165 billion dollars in 2015. Turkey became the seventh largest economy in Europe. It had a high rate of economic growth in 2014 with 8% .

Since 2002, Recep Tayyip Erdogan has been in power in Turkey. He was prime minister for 11 years till 2013 and then in 2014 became president of Turkey. During this period, his ruling party could change the picture of Turkey to a modern Islamic country. Turkey GDP has grown from a lowly 200 billion USD in 1995 to over 800 billion USD in 2014. The direct investment in Turkey reached to 165 billion dollars in 2015. Turkey became the seventh largest economy in Europe. It had a high rate of economic growth in 2014 with 8% .

President Duterte’s election into office has singlehandedly caused several changes in the political and social landscape. In just his first 6 months, the President managed to initiate a bloody and controversial drug war, pivot the country toward China and Russia, and show his all-out support for the Marcoses amid numerous angry protests nationwide.

President Duterte’s election into office has singlehandedly caused several changes in the political and social landscape. In just his first 6 months, the President managed to initiate a bloody and controversial drug war, pivot the country toward China and Russia, and show his all-out support for the Marcoses amid numerous angry protests nationwide.

Author’s note: Using the example of the Filipinos’ favorite snack, I discuss how factual information can be assembled to manufacture a lie. (Warning: Read the

Author’s note: Using the example of the Filipinos’ favorite snack, I discuss how factual information can be assembled to manufacture a lie. (Warning: Read the