![]() Fascism, someone wrote, comes in different forms to different societies so that people expecting fascism to develop in the “classic way” fail to recognize it even when it is already upon them. In 2016, fascism came to the Philippines in the form of Rodrigo Duterte, but this event continues to elude a large part of the citizenry, some owing to fierce loyalty to the president, some out of fear of what the political and ethical consequences would be of admitting that naked force is now the ruling principle in Philippine politics.

Fascism, someone wrote, comes in different forms to different societies so that people expecting fascism to develop in the “classic way” fail to recognize it even when it is already upon them. In 2016, fascism came to the Philippines in the form of Rodrigo Duterte, but this event continues to elude a large part of the citizenry, some owing to fierce loyalty to the president, some out of fear of what the political and ethical consequences would be of admitting that naked force is now the ruling principle in Philippine politics.

Why Duterte fits the 'F' word

At a panel I was part of in August of last year, one month after Duterte ascended to the presidency, there was considerable hesitation in using what panelists euphemistically called the “F” word to characterize the new Executive. There is an understandable reluctance to use the term fascist, undoubtedly because the word has been applied very loosely to all kinds of movements and leaders that depart, in some fashion, from liberal democratic practices, such as their propensity to resort to the use of force to achieve their political objectives.

However, there would probably be considerably less objection to the use of the word to describe Duterte if we see as central to the definition of a fascist leader a) a charismatic individual with strong inclinations toward authoritarian rule who b) derives his or her strength from a heated multiclass mass base, c) is engaged in or supports the systematic and massive violation of basic human, civil, and political rights, and d) proposes a political project that contradicts the fundamental values and aims of liberal democracy or social democracy.

If one were to accept these elements provisionally as the key characteristics of a fascist leader, then Duterte would easily fit the bill.

A fascist original

Having said that, one must nevertheless acknowledge that Duterte is a fascist personality that is an original.

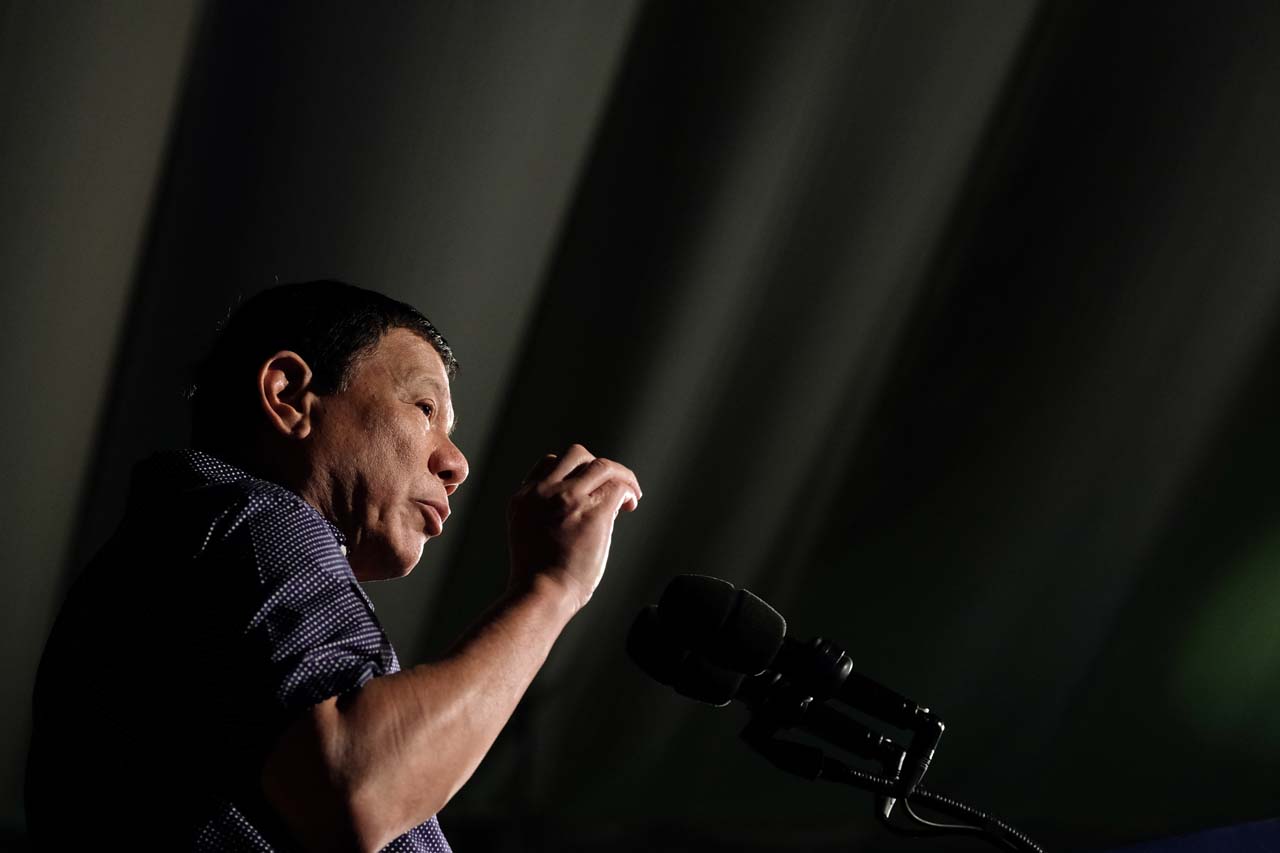

His charisma is not the demiurgic sort like Hitler’s nor does it derive so much from an emotional personal identification with the people and nation as in the case with some populists. Duterte’s charisma would probably be best described as “carino brutal,” a volatile mix of will to power, a commanding personality, and gangster charm that fulfills his followers’ deep-seated yearning for a father figure who will finally end the national chaos.

Duterte is not a reactionary seeking to restore a mythical past. He is not a conservative dedicated to defending the status quo. His project is oriented towards an authoritarian future. He is best described, using Arno Mayer’s term, as a counterrevolutionary. Unlike some of his predecessors, like Hitler and Mussolini, however, he is not waging a counterrevolution against the left or socialism. In Duterte’s case, the target, one can infer from his discourse and his actions, is liberal democracy, the dominant ideology and political system of our time. In this sense, he is both a local expression as well as a pioneer of an ongoing global phenomenon: the rebellion against liberal democratic values and liberal democratic discourse that Francis Fukuyama had declared as the “end of history” in the early 1990s.

Counterrevolutionaries are not always clear about what their next moves are, but they often have an instinctive sense of what would bring them closer to power. Ideological purity is not high on their agenda, with them putting the premium on the emotional power of their message rather on its ideological coherence. The low priority accorded to ideological coherence is also extended to political alliances. Duterte’s mobilization of a multiclass base and his ruling with the support of virtually all of the elite is unexceptional. However, one of the things that makes him a fascist original is that he has brought the dominant section of the left into his ruling coalition, something that would have been unthinkable with most previous fascist leaders.

But perhaps Duterte’s distinctive contribution to fascism as a political phenomenon is in the area of political methodology. The stylized paradigm of fascism coming to power has the fascist leader or party begin with violations of civil rights, followed by the power grab, then indiscriminate repression. Duterte turns this “Marcosian model” of “creeping fascism” around. He begins with impunity on a massive scale, that is, the extra-judicial killing of thousands of alleged drug users and pushers, and leaves the violations of civil liberties and the grab for absolute power as mopping up operations in a political landscape devoid of significant organized opposition.

![STOP THE KILLINGS. Protesters in Manila]()

A Product of EDSA

Duterte’s ascendancy cannot be understood without taking into consideration the debacle of the EDSA liberal democratic republic that was born in the uprising of 1986. In fact, EDSA’s failure was a condition for Duterte’s success.

What destroyed the EDSA project and paved the way for Duterte was the deadly combination of elite monopoly of the electoral system and neoliberal economic policies and the priority placed on foreign debt repayment imposed by Washington. By 2016, there was a yawning gap between the EDSA Republic’s promise of popular empowerment and wealth redistribution and the reality of massive poverty, scandalous inequality, and pervasive corruption.

And the EDSA Republic’s discourse of democracy, human rights, and rule of law had become a suffocating straitjacket for a majority of Filipinos who simply could not relate to it owing to the overpowering reality of their powerlessness. Duterte’s discourse – a mixture of outright death threats, basag-ulero language, and frenzied railing coupled with disdainful humor directed at the elite, whom he called “coños” or cunts – was a potent formula that proved exhilarating to his audience who felt themselves liberated from the stifling hypocrisy of the EDSA discourse.

Fascism in power

Probably no fascist personality since Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 has used the mandate of a plurality at the polls to reshape the political arena more swiftly and decisively than Duterte in 2016. Even before he formally assumed office, the extra-judicial killings began; the elite opposition disintegrated, with some 98% of the so-called “Yellow Party,” the Liberals, joining the Duterte Coalition; and Duterte achieved total control of both houses of Congress.

The Supreme Court, shying away from a confrontation, chose not to challenge the president’s decision to have the former dictator, Ferdinand Marcos, buried in the Libingan ng mg Bayani. A traditional bulwark of defense of human rights, the Catholic Church, exercised self-censorship, afraid that in a confrontation with a popular president who threatened to expose bishops and priests with mistresses and clerical child abusers, it was going to be a sure loser.

A novice in foreign policy, Duterte was able to combine personal resentment with acute political instinct to radically reshape the Philippines’ relationship with the big powers, notably the United States. What surprised many though was that there was very little protest in the Philippines at Duterte’s geopolitical reorientation given the stereotype of Filipinos being “little brown brothers.” What protest there was came mainly from traditional anti-American quarters which evinced skepticism about the president’s avowed intentions.

Here, Duterte again showed himself to be a masterful instinctive politician. As many have observed, coexisting with admiration for the US and US institutions exhibited by ordinary Filipinos is a strong undercurrent of resentment at the colonial subjugation of the country by the US, the unequal treaties that Washington has foisted on the country, and the overwhelming impact of the “American way of life” on local culture. One need not delve into the complex psychology of Hegel’s master-servant dialectic to understand that the undercurrent of the US-Philippine relationship has been the “struggle for recognition” of the dominated party. Duterte has been able to tap into this emotional underside of Filipinos in a way that the left has never been able to with its anti-imperialist program.

The anti-American comments from Duterte supporters that filled cyberspace were just as fierce as their attacks on critics of his war on drugs. Like many of his authoritarian predecessors elsewhere, Duterte has been able to splice nationalism and authoritarianism in a very effective fashion, though many progressives have seen this as mainly motivated by opportunism.

What surprises are in store for us?

So what other surprises should we expect from this fascist original?

Perhaps the best way to approach the question of what is likely to come is to ask the following: What are the chinks in Duterte’s armor? How would they affect the pursuit of Duterte’s program? What are the prospects for the opposition?

There are chinks in the Duterte armor, and one of them is the health and age of the president. Duterte has been candid about his medical problems and his dependence on the drug fentanyl, reportedly a strongly addictive substance that is 50 to 100 times stronger than morphine and has the same effects as heroin. The age factor is not unimportant, considering that the president is turning 72. Hitler became chancellor at 44 and Mussolini became prime minister at 39. For the successful pursuit of an ambitious political project, one’s energy level is not unimportant.

More problematic is the issue of institutionalizing the movement. The force driving Duterte’s electoral insurgency has not yet been converted into a mass movement. Duterte’s key advisers have recognized this, their analysis being that the reason Joseph Estrada was ousted in 2001 was because he was not able to fall back on an organized mass movement to protect him. Jun Evasco, the secretary of the cabinet and a long-time Duterte aide, is the key person the president is relying on to fill the breach by forming theKilusang Pagbabago (Movement for Reform) that was launched in August 2016.

Evasco’s vision is apparently a mass organization along the lines of those of the National Democratic Front, where he cut his political teeth. This won’t be easy since, as some analysts have pointed out, he would have to contend with competing projects from Duterte’s political allies, like the Pimentels, the Marcoses, and the Arroyos, who would prefer an old-style political formation that brings together elite personalities. Needless to say, a political formation along the lines of the latter would be the kiss of death for Duterte’s electoral insurgency.

A bigger hurdle would be failure to deliver on political and social reforms. Practically all of the key political and economic elites have declared allegiance to Duterte, so that one finds it difficult to see how he can deliver on his political and economic reform agenda without alienating key supporters.

The Marcoses, who still have their ill-gotten wealth stashed abroad, the Arroyos, who have been implicated in so many shady deals, and so many other elites, many of whom have cases pending before the Ombudsman, are not likely to be disciplined for corruption, especially given their very close links to Duterte. Nor will the Visayan Bloc, that has come in full force behind Duterte, agree to a law that will extend the very incomplete agrarian reform program. Nor will the big monopolists like Manuel Pangilinan and Ramon Ang, who have pledged fealty to him, submit without resistance to being divested of their corporate holdings.

This is not to say that Duterte is a puppet of the elites. Having a power base of his own that he can easily turn on friend or foe, he is beholden to no one. Indeed, one can argue that most of the elite have joined him mainly for their own protection, like small merchants paying protection money to the mafia. The issue, rather, is how serious he is about social reform and how willing he is to alienate his supporters among the elite.

The same goes for economic reform. Ending contractualization (or ENDO, for “End of Contract”), one of the president’s most prominent promises, is currently bogged down in efforts to arrive at a “win-win” solution for management and labor, and all the major labor federations are fast losing hope the administration will deliver on this.

As for macroeconomic policy, any departure from neoliberal principles on the part of orthodox technocrats like Budget Secretary Benjamin Diokno and National Economic Development Authority Director General Ernesto Pernia is far-fetched. Again, the question lies in how convinced Duterte is that neoliberalism is a dead end and how willing he is to incur the technocratic and bureaucratic displeasure and loss of confidence on the part of foreign investors that would be elicited by adopting a different economic paradigm.

Social and economic reform is Duterte’s Achilles heel, and the president himself is aware that popularity is a commodity that can disappear quickly in the absence of meaningful reforms. Dissatisfaction is fertile ground for the build-up of opposition. This spells danger for the country in the medium term.

Even if he is able to quickly create a mass-based party, Duterte, to stay securely in power, would find that he would need to resort to the repressive apparatuses of the state to quell discontent and opposition. This may not be too difficult a course to follow. As noted earlier, having led a bloody campaign that has already claimed over 6,000 lives, the suspension of civil liberties and the imposition of permanent emergency rule would be in the nature of “mopping up” operations for Duterte. It would be a walk in the park.

![VICE PRESIDENT ROBREDO. Leni Robredo is proclaimed the country's vice president on May 30, 2016. Photo by Ben Nabong/Rappler]()

The opposition

Does the opposition matter? The elite opposition is extremely weak at this point, with most of the Liberal Party having joined the Duterte bandwagon out of opportunism or fear. An opposition led by Vice President Leni Robredo, who resigned from Duterte’s cabinet after being told not to attend meetings, is not likely to be viable.

While undoubtedly possessing integrity, Robredo has shown poor judgment, receptiveness to bad advice, and little demonstrated capacity for national leadership, and is, in the view even of some of her supporters, largely a political creation of Liberal Party operatives who wanted to convert the name of her deceased husband, former Department of the Interior and Local Government head Jesse Robredo, into political capital.

Moreover, her continuing strong ties to the double-faced Liberal Party and the former administration lend her to becoming easily discredited among both Duterte supporters and opponents.

The Left in crisis

This brings up the left.

Duterte’s coming to power created a crisis for the left. For one sector of the left, Akbayan, the social democratic left that had allied itself uncritically with the Aquino administration, Duterte’s ascendancy meant their marginalization from power along with the Liberal Party, for which they had, with their leadership’s eyes wide open, become the grassroots organizing arm.

For the traditional, or what some called the “extreme left,” Duterte posed a problem of another kind. While the National Democratic Front and Communist Party had not supported Duterte’s candidacy, they accepted Duterte’s offer of 3 cabinet or cabinet-level positions, as secretaries of the Department of Agrarian Reform and the Department of Social Welfare and Development and chair of the National Anti-Poverty Commission. They also accepted the president’s offer to initiate negotiations to arrive at a final peace agreement.

For Duterte, the entry of personalities associated with the Communist Party into his cabinet provided a left gloss to his regime, a proof that he was progressive, “a socialist, but only up to my armpits,” as he put it colorfully during his victory speech in Davao City on June 4, 2016.

It soon became clear that Duterte had the better part of the bargain. As the regime’s central policy of killing drug users and pushers without due process escalated, the left’s role in the cabinet became increasingly difficult to justify. This dilemma was compounded by the fact that no new land reform law was passed that would allow agrarian reform to continue, there was little movement in the administration’s promise to end contractualization, and macroeconomic policy continued along neo-liberal lines.

The left, however, found it hard to shelve the peace negotiations, from which they had already made some gains, and to part from heading up government agencies that gave them unparalleled governmental resources to expand their mass base.

Duterte had again displayed his acute political instincts. Knowing that the traditional left was at ebb in its fortunes, he gambled that they would accept his offer of cabinet positions. And having accepted these and agreeing to open up peace negotiations from which it could get many more concessions than it would have gotten under previous administrations, the left, he knew, would find it extremely difficult to part from the positions of power it had gained.

The price, the leaders of the left realized, would be high, and this was their association with a bloodthirsty regime. The Communist Party and its mass organizations tried to alleviate the contradiction by issuing statements condemning Duterte’s bloody policies. But this only made their dilemma keener, since people would ask, why then do you continue to provide legitimacy to this administration by staying on in the cabinet? Unlike Hitler and Mussolini, Duterte brought the left into his regime, but in doing so, he has been able to sandbag it and subordinate it as a political force. So far, that is.

Whether he is fully conscious of it or not, Duterte’s ascendancy has severely shaken all significant political institutions and political players in the country, from right to left.

Civil society mobilizes

Where opposition to Duterte has developed over the last 6 months has been from civil society. A leading force is I Defend, a broad grouping of over 50 people’s organizations and non-governmental organizations that has waged an unremitting struggle against the extra-judicial killings. Another is the coalition against the Marcos burial at the Libingan ng mga Bayani.

While Malacanang has painted these formations as “dilawan,” or yellow, the reality is that most of their partisans are progressives that are as opposed to a “yellow restoration” as they are to Duterte’s policies, as well as newer and younger forces drawn from the post-EDSA and millennial generations that have become alarmed at Duterte’s fascist turn.

This growing opposition does not seek a reprise of 1986, perhaps heeding Marx’s warning that “history first unfolds as tragedy, then repeats itself as comedy.” It is increasingly realizing that the fight for human rights and due process must be joined to a revolutionary program of participatory politics and economic democracy – to socialism, in the view of many – if it is to turn the fascist tide. There is no going back to EDSA.

What the opposition still has to internalize though is that opposing fascism in power will not be, to borrow a saying from Mao, “a dinner party,” that it will indeed be exceedingly difficult and demand great sacrifices. Moreover, there is no guarantee of success in the short or medium term. Fascism in power can be extraordinarily long-lived. The Franco regime in Spain lasted 39 years, while Salazar’s Estado Novo in neighboring Portugal went on for 42 years.

Like the anti-Marcos resistance 4 decades back, the only certainty members of the anti-fascist front can count on is that they’re doing the right thing. And that, for some, is a certainty worth dying for. – Rappler.com

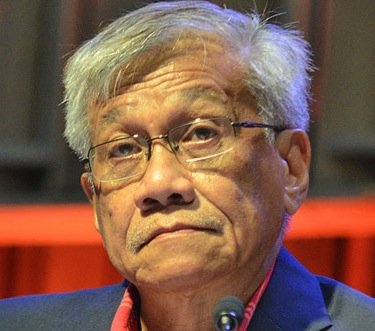

Walden Bello made the only recorded resignation out of principle in the history of the Congress of the Republic of the Philippines in 2015 owing to what he saw as the Aquino administration’s double standards in dealing with corruption, failure to deliver economic and social reform, and subservience to the United States. An anti-dictatorship activist, he was principal author of Development Debacle: The World Bank in the Philippines, which exposed the Marcos-World Bank alliance in forging the export-oriented capitalist development model. A retired professor of sociology at the University of the Philippines, he is currently senior research fellow at Kyoto University and professor of sociology at the State University of New York at Binghamton.

This article is an abbreviated adaptation of a much longer piece that has been solicited by and submitted to the Philippine Sociological Review and is published by Rappler with the permission of PSR.

![]()

Congressional debate on martial law has suddenly taken public attention when

Congressional debate on martial law has suddenly taken public attention when

The Americans have never had a ruder and unlikelier awakener than Donald Trump: he has done it with antithetical values – he is sexist, homophobic, and xenophobic. And he is taking over as their president this New Year.

The Americans have never had a ruder and unlikelier awakener than Donald Trump: he has done it with antithetical values – he is sexist, homophobic, and xenophobic. And he is taking over as their president this New Year.

Fascism, someone wrote, comes in different forms to different societies so that people expecting fascism to develop in the “classic way” fail to recognize it even when it is already upon them. In 2016, fascism came to the Philippines in the form of Rodrigo Duterte, but this event continues to elude a large part of the citizenry, some owing to fierce loyalty to the president, some out of fear of what the political and ethical consequences would be of admitting that naked force is now the ruling principle in Philippine politics.

Fascism, someone wrote, comes in different forms to different societies so that people expecting fascism to develop in the “classic way” fail to recognize it even when it is already upon them. In 2016, fascism came to the Philippines in the form of Rodrigo Duterte, but this event continues to elude a large part of the citizenry, some owing to fierce loyalty to the president, some out of fear of what the political and ethical consequences would be of admitting that naked force is now the ruling principle in Philippine politics.

[On December 12, 2016, Miguel Syjuco, the novelist, posted on Facebook his agreement with

[On December 12, 2016, Miguel Syjuco, the novelist, posted on Facebook his agreement with

![[Dash of SAS] Ana Santos](http://static.rappler.com/images/ana-santos-150.png) It was around Christmas time in 2012, then President Benigno Aquino III quietly signed the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health (RH) Act into law. It was the fulfillment of Aquino’s promise to give every Filipino the RH information and services they need to plan for their families.

It was around Christmas time in 2012, then President Benigno Aquino III quietly signed the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health (RH) Act into law. It was the fulfillment of Aquino’s promise to give every Filipino the RH information and services they need to plan for their families.

This is the first of a series of articles the authors (and other collaborators) will be writing on constitutional change. The intent of the series is to influence the process of amending or revising the Constitution that is about to be launched this January.

This is the first of a series of articles the authors (and other collaborators) will be writing on constitutional change. The intent of the series is to influence the process of amending or revising the Constitution that is about to be launched this January.

Combating social inequality is hard in itself. But the recent debacle over the proposed SSS (Social Security System) pension hike highlights the even tougher task of redressing inequality across generations: that is, balancing the welfare of current and future Filipinos.

Combating social inequality is hard in itself. But the recent debacle over the proposed SSS (Social Security System) pension hike highlights the even tougher task of redressing inequality across generations: that is, balancing the welfare of current and future Filipinos.

Consider this a work of speculative fiction.

Consider this a work of speculative fiction.

Later this month, the government and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) enter their third round of talks under the Duterte administration. Foremost in the agenda is the second substantive agreement - the Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms (CASER).

Later this month, the government and the National Democratic Front of the Philippines (NDFP) enter their third round of talks under the Duterte administration. Foremost in the agenda is the second substantive agreement - the Comprehensive Agreement on Social and Economic Reforms (CASER).