Al Gore’s An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power comes at a convenient time. The documentary film, which was released globally on August 4, is the Nobel Peace Prize winner’s latest project in a long-running climate change crusade. Its narrative weaves together both good and bad developments over the past decade, as footage of collapsing polar ice caps and flattened towns in Tacloban, eventually gives way to cutting-edge Texas solar farms, impassioned crowds at the Global Climate March, and a jubilant Paris in December 2015.

The film’s tone is largely hopeful, and plainly at odds with political reality. As the filmmakers took pains to emphasize, not everyone has responded affirmatively to Gore’s urgent call to arms. The question of the moment persists: what does Trump’s decision to withdraw from the Paris climate accord mean for the rest of the world? What does it mean for the Philippines?

19 against one

In its pursuit of a “healthy planet”, the global community will not be hindered. This was the answer that rang loud and clear at the G20 summit last month, as 19 world leaders stood together against United States President Donald Trump to affirm their commitment to the Paris Agreement. Efforts in the battle against climate change may have a long way to go, but this united front was a triumph for both developed and developing nations.

The Paris Agreement, later lauded as “the world’s greatest diplomatic success”, was adopted unanimously in December 2015. Its goal was to limit the global temperature rise this century to below two degrees above pre-industrial levels. Each country contributed its own target and deadline: among others, then president Barack Obama pledged to reduce US greenhouse gas emissions by 26-28% below 2005 levels by 2025, and the Philippines, to reduce its carbon emissions by 70% by 2030.

Last month, Trump faced backlash when he announced his intention to withdraw from the accord. If finalized, the US will join Nicaragua (which thought the provisions too lenient on developed countries) and Syria (which remains mired in a civil war) as the only nations not party to it.

The annual G20 summit was the first major meeting of world leaders since Trump’s announcement. This year, the governments of 20 leading economies gathered in Hamburg, Germany from July 7-8. As the possibility of the US’ withdrawal loomed over Hamburg Messe, the issue of climate change took centerstage.

Over the two days, the German Chancellor and current G20 President, Angela Merkel, went to great lengths to maintain solidarity during negotiations, while Trump remained glaringly isolated. This discord inevitably manifested in the communiqué, the group’s political declaration.

In the same breath that they proclaimed their “strong commitment to the Paris Agreement” and intention to move “swiftly towards its full implementation”, the rest of the G20 recognized that the US’ priorities clearly lay elsewhere; namely, in the revival of its fossil fuel industry, which Trump believed would bring it economic prosperity.

Worries in the wake

The immediate concern was that Trump had set a precedent for others to wane in their support of the Paris process. Developing nations in particular, some speculated, might be discouraged by the reduced funding that would result from the US’ withdrawal. Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, which was reiterated in the communiqué, obligated developed countries to provide aid to their developing counterparts for use in emission reduction efforts. The absence of the US’ contribution could mean a cut of as much as $3 billion.

The misfortune that did come to pass was that the compromises made to appease the US weakened an already inadequate approach to climate change/the crisis. Pundits considered that the Paris Agreement, for all the good intentions it indicated, left much to be desired.

“Countries’ plans for action…as currently formulated, only take us about one-third of the way on the emissions reductions we need to be on course for a two-degree world,” writes Andrew Norton, director of the International Institute for Environment and Development. The compromises in the G20 communiqué meant that what could have been a call for greater ambition, fell short.

“If you measure [the summit] against what's really necessary, then it's far too weak,” said Niklas Höhne, director of the NewClimate Institute. “Right now, all countries are saying: ‘We are doing what we have proposed, we are not taking steps backwards.’ And that's definitely not sufficient if you look at what really is necessary to save the climate.”

For now, the unity displayed at the G20 summit despite, and perhaps even due to, Trump, seems to have tempered these concerns. The few countries most in danger of being influenced by the US’ brazen move – Saudi Arabia, Indonesia, Russia and Turkey – ultimately backed the accord. Moreover, Höhne said, “What's more important are the other major emitters like India, China, India, Brazil, Mexico, South Korea – and they have all been very positive and are continuing with their part.”

The return of the prodigal American?

The hope is that the United States’ absence is temporary, which is not far-fetched. For one, Trump’s economic reasons are no longer compelling, if they ever were. In his speech delivered on June 1, he claimed that staying in the Paris accord could pose “serious obstacles” to maximizing America’s natural energy reserves and thereby hinder its economy.

Alden Meyer of the US Union of Concerned Scientists dispels this, asserting that there is an “accelerating shift away from polluting fossil fuels towards a global economy powered by clean, renewable energy.” Unlike the fossil fuel industry, clean energy is estimated at over $20 trillion and is “providing good jobs that can put people to work and revitalize American manufacturing, in ‘blue’ and ‘red’ states,” writes Robert Redford, a director and trustee of the Natural Resources Defense Council.

Pressure from the domestic American and international communities continues to mount. Just days after Trump’s speech, over 1,200 American cities, states, universities and businesses signed and submitted “We Are Still In” to the United Nations, articulating their pursuit of the Paris goals.

In early July, this was followed by “America’s Pledge”, which provides a concrete framework for state and non-state actors to track their emissions. Initiatives like these affirm American society’s – if not Trump’s – commitment to the Paris climate accord. As for the rest of the world, the marked 19-1 division during the G20 summit said it all.

Perhaps most importantly, Trump cannot withdraw yet. In a press release issued last Friday, August 11, the US State Department announced that it had formally notified the UN of its decision, but recognized that it is presently not “eligible” to act on it.

Under Article 28, withdrawal from the Paris Agreement is not permitted for the first 3 years after the accord comes into effect, and thereafter, is subject to a one-year notice period. This brings the earliest possible date of withdrawal to November 2020. Alternatively, Trump could withdraw the US from the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) effective immediately, but with monumentally graver implications.

In the interim, the US’ political obligation remains, and Trump may yet be convinced to stay. He is open to “re-engaging” the accord if more America-friendly terms can be negotiated, although such concessions seem unlikely given the vehement opposition previously expressed by the leaders of France, Germany, and Italy.

Nevertheless, French President Emmanuel Macron is optimistic about swaying the enfant terrible. “He told me that he would try to find a solution in the coming months,” Macron said, following Trump’s mid-July state visit to France. “We talked in detail about what could enable him to come back into the Paris accords.”

![]()

Better without the US

Coincidentally, the US’ break from the climate change scene may be exactly what the rest of the world needs. The issues most important to climate justice would benefit from a temporary US withdrawal, as issues like adaptation, climate finance, technology transfer, and loss and damage could be more easily resolved without the US at the negotiating table.

In the race against environmental degradation, the absence of Trump’s contrarianism would allow vital ground to be more quickly gained. However, this must be balanced with the need to continue to involve American career diplomats and officials in the process to pave the way for the US’ eventual re-entry. Judging from the press release, the US is only more than willing to do so, and intends to “continue to participate in international climate change negotiations and meetings…to protect US interests and ensure all future policy options remain open to the administration.”

The unintended but most auspicious by-product of Trump’s announcement was a world deliberately united against climate change: save for Trump, all the G20 members acceded to the communiqué. With one voice, they declared, “The Leaders of the other G20 members state that the Paris Agreement is irreversible.”

Although US participation will always be preferred, the communiqué is proof that an effective climate change agreement can exist without it. “The US president’s weak attempts to capsize the climate movement have failed,” observed Mohamed Adow, international climate lead at Christian Aid. “The rest of the world is moving ahead.”

Everyone’s battle

Climate change has long been treated as a tug-of-war between developed nations, dictated by first-world politics and ivory tower planning. The stark reality is that it is everyone’s battle, most especially that of developing nations.

In recent years, the Philippines has been among those who have taken this to heart and stepped up their efforts. Following the Super Typhoon Yolanda (Haiyan) tragedy, it successfully pushed for the establishment of the Warsaw International Mechanism on Loss and Damage at the UNFCCC Conference of Parties 2013, and in 2016, oversaw the Climate Vulnerable Forum’s adoption of the Manila-Paris Declaration as forum chair.

When President Rodrigo Duterte signed the Paris Agreement, Senator Loren Legarda christened it one of the Philippine government’s “shining achievements” as it “allows our country access to international climate finance mechanisms and to acquire support from developed countries for adaptation, mitigation, technology development and transfer, and capacity building.”

The immediate challenge for developing nations is to take robust action to maximize these resources. As Duterte told the crowd at his recent State of the Nation Address, now more than ever, “The protection of the environment…is non-negotiable.”

When a lone mutineer threatened to sabotage the climate change battle effort, the global community – in the form of an irrevocable communiqué – proved that would not be tolerated. To make good on its word, it must continue to build momentum towards a holistic and effective approach to climate change.

These efforts will hopefully see the US’ return, but regardless. Climate change is too big an issue for us to allow one country to hold the global community hostage and paralyzed in inaction. Fortunately, the world at the G20 summit didn’t have to be told.

An Inconvenient Sequel: Truth to Power hits theaters in the Philippines in late August. Watch it, be disturbed by it, and speak truth to power: to our government, to our coal and fossil fuel-dependent industries, and to our fellow citizens. Let’s fight as if the survival of our islands depend on it. In fact, it does. – Rappler.com

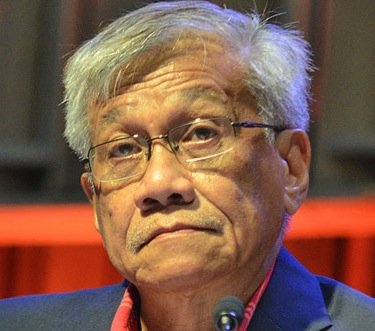

Tony La Viña is former dean of the Ateneo School of Government. Hannah Tablan is a final year law student at King's College London. This past summer, she was a Kaya Collaborative Fellow assigned to the Manila Observatory under the tutelage of Dean La Viña.

![]()

The week has seen the two latest cases of deviancy in the Duterte government.

The week has seen the two latest cases of deviancy in the Duterte government.

Upon reading the news about the the

Upon reading the news about the the

The unfolding drama surrounding LTFRB’s regulation of ride-hailing services (especially Uber) is of particular interest to teachers of economics: it’s a perfect illustration of the basic model of supply and demand.

The unfolding drama surrounding LTFRB’s regulation of ride-hailing services (especially Uber) is of particular interest to teachers of economics: it’s a perfect illustration of the basic model of supply and demand.

On August 15, 2017, in one big sweep, 32 drug suspects were killed by the Philippine National Police (PNP) officers in the province of Bulacan. That day has the dubious recognition of having the most number of deaths in a single day in the continuing war on drugs.

On August 15, 2017, in one big sweep, 32 drug suspects were killed by the Philippine National Police (PNP) officers in the province of Bulacan. That day has the dubious recognition of having the most number of deaths in a single day in the continuing war on drugs.