![ON JOURNALISM. 'Journalism’s best weapon against lies is to be transparent, thorough and provocative,' says Tina Monzon-Palma]()

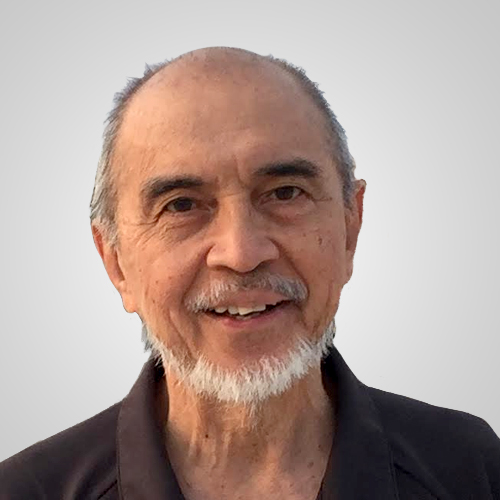

Below is the full text of the speech veteran broadcast journalist Tina Monzon-Palma delivered at the University of the Philippines' Gawad Plaridel awarding ceremony when she received her award.

Maraming-maraming salamat po, sa lahat po ng naging bahagi nitong parangal na ito.

Maraming-maraming salamat sa Unibersidad (ng Pilipinas), at sa lahat po ng mga kaibigan ko, nakatrabaho ko, nagbigay ng inspirasyon para kami ay maging isang mahusay na organisasyon, sa lahat ng istasyon na sinalihan ko, maraming salamat.

I just cry at the start but the rest is going be fun.

I’ll tell you a fun story, going back to the episode that Dr (Mike) Tan was talking about with his father:

I did the newscast in ANC, The World Tonight, at 10 o’clock, so every day, I would go back from the house, after dinner, and go to the make-up room at about 8:30 pm.

So I park the car in the basement and take a long walk and go to the area where they have the make-up rooms, punch my ID in the turnstile. In the corner of my eye, outside the studio of Vice Ganda, I don’t know what number that is, there were 3 musikeros.

Alam mo yung kumakanta na parang Apeng Daldal, yung mga tumatawa, kilala nila. Ito yung mga kumakanta sa mga restawran, ng mga“Yellow Bird”, “Besame Mucho”, those kinds of songs.

May isa doon sa tatlo na may hawak-hawak ng gitara na nakatitig sa akin, so tinignan ko siya, tapos lumapit s’ya,“Ma’am, mawalang galang na po, kayo po ba si Tina Monzon Palma ng GMA7?”

“Dati po,” sabi ko, “Pero nandito na ako.”

“Ay,” sabi niya, “Ang ganda-ganda n’yo pala sa personal.”

‘Di ba? Wala pa akong make-up noon, ha.

I take about 1-6 steps.

He says, “Pare, si Tina Monzon Palma, nandito na sa ABS-CBN, buhay pa pala ‘yon!” (Audience laughs)

That is why I have both feet on the ground, I’m still alive.

To the younger generation here, I am the veteran under the Cory administration of about 7 coup attempts. And my colleagues are here from Channel 7, Marissa Flores, Grace [dela Peña], Jessica Soho, Luz Rimban, and my cameraman.

We were all together.

So one of the things that we did at the little training from the generals then, was that, when there would be an attempt, the first thing you do is take out the exciter.

It is a broadcast piece of equipment that actually, after my talk with retired broadcast engineer Morato, controls the frequencies of the channel. So nilabas ko yon, and Marisa [Flores] who is here, remembers that I told her to bring the exciter home and she brought it to my house.

And there was another incident where I told another PA to bring the exciter. That’s because there were 7 coup attempts.

In between those coup attempts I would talk to the coup plotters, threatening me not to go on the air.

I said, “Sir, I cannot go on the air because I have no exciter.”

So that’s the end of the story. But then the government of Cory would ask me, “Why aren’t you on the air?”

I said, “I took out the exciter for the EDSA studio but the Channel 7 on Broadway Center could transmit, actually.”

“Why don’t you go on the air on Channel 7 Broadway and we will broadcast using that channel for President Cory Aquino to be able to send a message in the afternoon to the public.”

So I said, “Sure, send them here.”

I did not have the facility for a microwave. None of the PLDT guys wanted to go up the tower of 7 to catch the signal of the microwave from Malacañang, so they could go on broadcast.

So those incidents and many, many other incidents have actually made my years really significant, in the life of this country as far as journalism and democracy are concerned.

The story sounds funny to me and to those who were there at that time.

But I look back, I can tell you I was being reckless and silly and foolish, not resourceful and brave.

Talagang mabilis lang akong mag-isip… “Tangalin ‘yan…”

They were even asking me at some point when they found out that there was a group of plotters who could transmit using some makeshift equipment to broadcast on a separate band and be heard on a limited area only.

The military told me to point to them where the elements of the tower of channel 7 and our radio station, so they could harpoon it and tear it down.

But that’s going to be the subject of some other story.

So I admit I was reckless and not resourceful at all sometimes. I did not actually think that anything would come of that stunt I pulled, but I knew I had to do something.

We try to pretend we are brave and somehow that little piece of courage sees us through, but I kept my wits and harnessed all the smarts we’ve learned through the years and I’m still...to this day, proud to remember all of those days.

You’ve all seen that overused, trite, cliché drawing of the candle in the dark? That symbol came to life from that little piece of courage we all try to keep alive.

This is gonna make me cry again. One person carried the strongest flame and she was a friend – unwavering, clear-headed. Letty Jimenez Magsanoc, you know her?

A month ago, I read with sadness that the Prietos had sold a majority stake in the newspaper that started as a “mosquito press.”

I wonder how my dear friend Letty would have reacted. I wonder if it would have happened at all if she was still around at the helm. Sadly, these are not questions I can ever answer.

Thinking about Letty led my mind to wander back to the early year of the 1980s, when media played a key role in awakening a nation from two decades of slumber.

Looking back at Martial Law, people talk about the First Quarter Storm and the events leading up to the February Revolution. I stayed throughout the years of Martial Law.

That episode that was put on the screen about my wanting to ask a question and not letting go of the opportunity was an interview with President Ferdinand Marcos on the eve, or two days before the snap elections.

They had put together all the anchors of the TV stations and I put in Dong Puno to be the representative of Channel 7.

There were others there from Channel 9, from Channel 4 etc, Channel 13, but one day after, they say, “Ma’am they like you to be on the panel.”

I said, “No, I sent already, Dong Puno as a representative.” And so I turned it down.

And then another guy, who I happen to know who works with Marcos said, “Pare makisama ka naman, o.”

Sabi n’ya. “Hinihingi ka, eh. Hinihingi kang maupo.”

“Eh, nandun na si Dong, anong gagawin ko doon?” I said.

He said, “Pare, pakikisama mo lang, nakikiusap ako.”

So I go there, we’re in this panel, a horseshoe panel.

The first thing that I see is the President of the Philippines who said he was fit, being carried by the PSG. Carried, his feet were not on the floor.

I said, “I will never have this chance again.”

And so I said, “I saw you being carried by your PSG, is there something that you’re feeling that we should know about?”

And then all of a sudden they put on the screen body-building video. Anyway, he was able to give an excuse for that.

So there was another round that went on, and I was the last in that round.

“Sir,” sabi ko,“I’m sitting a few feet away from you and I can see that you have a lot of needle marks.” And I could, I’m looking for that tape, I could not honestly remember what he answered.

But my sister tells me, my dad was watching at home, and he was telling my sister, “Hoy, ano naman ang tinanong ni Christine? Nakakatakot yun! Baka s’ya mahuli!” But nothing of that sort happened.

You talk about the years, but few talk about the years in between, the hard years, the darkest hours, the years, when all hope seemed lost and no silver lining was in sight.

These were the years when almost everything you watched, heard or read were a tepid, timid and whitewashed version of reality.

These were the years, if you were from UP you must know this, there were years when people lived in fear of the knock on the door in the night, which often ended with people dying or going missing to this day.

But wait, this generation IS living through a version of that time. PRE-EDSA 2.0.

I’m talking about the crony press, but you call it fake news.

In many ways those years are uncannily similar today, don’t you think? Nobody’s answering. (Audience: Yes!) Except that everything is on steroids.

During those years, everything was placid above ground but there was groundswell underneath. I’m thinking, “How fast will this generation’s volcano explode?” Everything happens 10 times faster.

The fires of defiance, disobedience, and struggle were lit by a magazine called Mr and Ms. It was a voice in the wilderness. In a way we’re back in the wilderness – when before we had censorship, now we are in a wasteland of hate and intolerance. Do you feel that?

Why am I telling you this? Because my main takeaway is, it is darkest before the dawn.

As journalists, what role do we play in this new wave of authoritarianism and hate speech?

Do we still matter – as the role of gatekeeper shifts from content producers to curators like Facebook?

Before the advent of fake news, many were saying, the journalist will be replaced by the citizen journalists.

But as truth becomes blurred, our role once again becomes clear. And what is the role of the journalist? To investigate, cut through the white noise, present the situation as clearly as possible and as Vergel [Santos] would always tell us, ask the hard questions.

There was a time when news programs on TV and radio were the number one sources of news.

That has dramatically changed. Increasingly, these programs share the influence over audiences with the internet.

Ironically, as the internet democratized opinion dissemination, media lost its halo.

Fake news and the proponents of the campaign line “media is bias” (without the ED) eroded trust in media. But stress, our trade depends on trust. In the absence of truth, you have no choice but to believe the person in power.

How do we remain relevant in an age when truth itself seems to be under assault?

There is only one answer, my friends, especially the younger generation. The media cannot be timid. Media need not be timid if it sticks to good journalism.

You will never feel afraid if you know what you write about is the truth, you’ve been able to do your vetting and you’ve been able to consult, if you’re writing for a newspaper or producing a newscast with your editors, they would have made sure you do a really good job.

Journalism’s best weapon against lies is to be transparent, thorough and provocative.

When mainstream media descends into unobtrusiveness, it does its audience a disservice.

When media masters the art of camouflage, the people will forget.

When media becomes muted, we let the underlying message behind the trolls and the propaganda machines to dominate the discourse.

What is this underlying message? Edward R. Murrow, does anybody know who he is?

Murrow is a favorite radio-TV personality of ours. Angelo Castro, we always talk about him.

What is this underlying message according to Edward R. Murrow? He named that evil a long time ago.

That is when people equate dissent with disloyalty.

Let me give you a quick example. In one of those coup attempts in 1990, soldiers who took over two military camps, I think in Cagayan or Butuan or Iligan, this is Colonel Alexander Noble.

And Jessica would know this because she was the reporter who was flying in with a bunch of tapes and I was on the phone for 5 hours talking to all the generals and all the people In the Palace.

They were appealing to me, because they had been able to stop the rebellion at that time.

So they had talked to me to say, “Don’t show it anymore.”

I said, “Why not, sir?”

Because there might be sympathizers, and they're unsure that they had actually quelled whatever it was that was there. But I said, “No, Jessica, go ahead write your story.”

She was nearly crying and she said, “Ma’am, i-e-ere ba ito?” I said, “I-e-ere ‘yan. Let me just deal with these people.”

Jose Marie Velez was so impatient and didn’t want to deal with my ordeal of being challenged by all of these people.

This general who was the highest-ranking general at that time said, “Tina, can I just make an appeal to you? We’re in a very delicate situation. We’ve been able to quell.”

Sabi ko, “Sir, ganito na lang, you did a good job, you do your job, and I will do my job.” And I put the phone down. And I was wondering, did you think I was going to be treasonous at that point when I was just airing a story? People had to know that there was this bunch of military guys who wanted to establish the republic of Mindanao. They had even printed their own currency at that time.

So these were difficult times, and every time I remembered the story, that carried me on. You cannot be challenged if you know the truth, if you personally know the truth, you trust the organization and the people you work with. They cannot break it, they can only invent things.

To everyone, especially the millennials:

Wala tayong karapatang manghiya, manindak at magpalaganap ng pagkamuhi.

May karapatan tayong maging-weird, maging kakaiba at magkamali.

May karapatan tayong tumuligsa magtanong at magpahayag.

To all of you my friends, you are in media now, 30 years ago media answered that call. Now it is your turn. Maraming, maraming salamat po.– Rappler.com

![]()

Duterte has no qualms that his war on drugs is bloody. He is even proud of it. But when his war kills innocent lives, his administration and supporters have a ready excuse: collateral damage.

Duterte has no qualms that his war on drugs is bloody. He is even proud of it. But when his war kills innocent lives, his administration and supporters have a ready excuse: collateral damage.

Like others who did not assume that the peace talks between the government of the Philippines and the National Democratic Front (NDF) were doomed from the start, I have wondered why President Rodrigo Duterte

Like others who did not assume that the peace talks between the government of the Philippines and the National Democratic Front (NDF) were doomed from the start, I have wondered why President Rodrigo Duterte

Late in the evening of August 6, the video of Patricia Bautista, estranged wife of Commission on Elections (Comelec) Chairman Andres Bautista, was uploaded on Youtube publicly. She claims that her husband “might” have amassed nearly P1 billion worth of ill-gotten wealth. Few hours after, on the front page of the Philippine Daily Inquirer ran the headline “Wife says poll chief has ill-gotten wealth,” shocking the nation.

Late in the evening of August 6, the video of Patricia Bautista, estranged wife of Commission on Elections (Comelec) Chairman Andres Bautista, was uploaded on Youtube publicly. She claims that her husband “might” have amassed nearly P1 billion worth of ill-gotten wealth. Few hours after, on the front page of the Philippine Daily Inquirer ran the headline “Wife says poll chief has ill-gotten wealth,” shocking the nation.

Restless and disturbed, I went to Caloocan City Sunday night, August 20, with friends to visit the boy named Kian de los Santos. Waze could only get us onto NLEX and the West Service Road. Beyond that, we had to resort to good, old pagtatanong-tanong to find Kian.

Restless and disturbed, I went to Caloocan City Sunday night, August 20, with friends to visit the boy named Kian de los Santos. Waze could only get us onto NLEX and the West Service Road. Beyond that, we had to resort to good, old pagtatanong-tanong to find Kian.

For over a year now, we have been appealing to President Rodrigo Duterte to stop his so-called “war on drugs” – and not because we do not want the drug problem to be solved but precisely because we want it solved and his “

For over a year now, we have been appealing to President Rodrigo Duterte to stop his so-called “war on drugs” – and not because we do not want the drug problem to be solved but precisely because we want it solved and his “

In 2020, the pioneering broadcast network ABS-CBN will lose its franchise

In 2020, the pioneering broadcast network ABS-CBN will lose its franchise

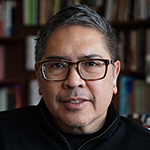

What is the relationship between fact and fiction? This question has a long history, but in the age of so-called fake news and the manic speed of social media, it has taken on a renewed urgency. What follows are my very sketchy attempts to sort through this question.

What is the relationship between fact and fiction? This question has a long history, but in the age of so-called fake news and the manic speed of social media, it has taken on a renewed urgency. What follows are my very sketchy attempts to sort through this question. In truth I really wanted to decry the death of

In truth I really wanted to decry the death of

The tragic death of 17-year-old

The tragic death of 17-year-old